by Natalie Marchant*

Plastic pollution in the ocean could be an even bigger problem than first feared, with 14.4 million tonnes of microplastics estimated to be at the bottom of the sea.

The figure is more than double the amount of plastic thought to be on the ocean’s surface, according to a team from Australia’s national science agency, the Commonwealth Industrial and Scientific Organisation (CSIRO).

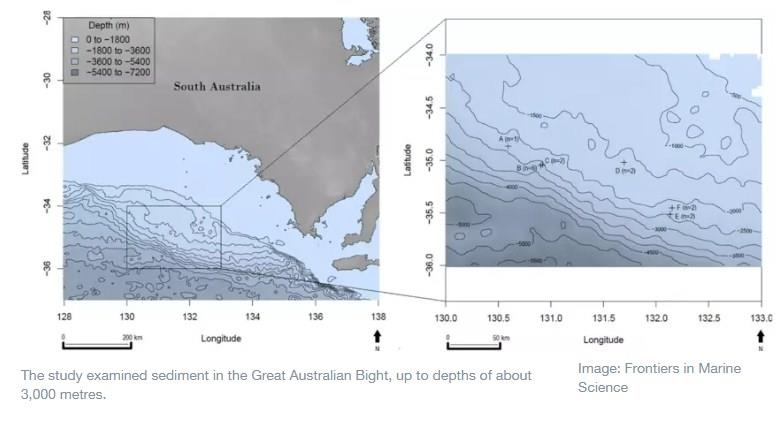

Researchers made the estimate – which they say is the first of its kind – after examining sediment in depths of up to 3,062 metres in the Great Australian Bight, a pristine marine environment off the country’s south coast.

Using a robotic submarine, scientists collected and analyzed samples from six sites between 288 and 356 kilometres offshore.

The amount of microplastics – plastic fragments under 5mm in length and which can be harmful to marine life – in the sediment were found to be some 25 times higher than previous studies.

In addition, the number of microplastics on the seafloor were generally higher in areas where there was more rubbish floating on the surface.

A microplastics ‘sink’

The CSIRO team then scaled up their results according to the size of the ocean in order to calculate a worldwide estimate of the amount of microplastics on the seafloor.

“Our research found that the deep ocean is a sink for microplastics,” Dr Denise Hardesty, principal research scientist and co-author said in a statement.

“We were surprised to observe high microplastic loads in such a remote location,” she added. “By identifying where and how much microplastic there is, we get a better picture of the extent of the problem.”

A global problem

Scientists argue that the results highlight the need for urgent action to tackle the problem of microplastic pollution of the ocean.

Dr Jennifer Lavers, of the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania, told the Guardian that microplastics pose a particular threat because their size means there are more species to eat them, leading to the entire food web being infiltrated.

“Everything that is tiny is at the base of the food web so it’s not an issue of just an albatross swallowing a cigarette lighter or a sperm whale swallowing a big chunk of net, you now literally have microplastics being eaten by corals, sea cucumbers, clams and mussels, and zooplankton at the very base of the food web.”

Myriad uses

Plastic itself is not necessarily the problem. It is durable, hardwearing and long lasting – with much of it being easily recyclable or, at the very least, reusable.

The material can prove vital in preserving food to reduce waste, keeping medical devices sterile and producing safety equipment, among myriad other uses.

Human dependence on single-use plastic – particularly kinds where alternatives exist, such as drinking straws or disposable cutlery – remains a problem across the world, however, as do issues relating to its disposal.

Used, not used up

Global efforts to tackle plastic pollution were under way before the pandemic, but the soaring rise in the use of personal protective equipment, closed and inadequate recycling facilities and the suspension of government-backed environmental programmes have exacerbated the issue.

The World Economic Forum-backed initiative Global Plastic Action Partnership (GPAP) estimates that 8 million tonnes of plastic waste leaks into the ocean each year. Its recent Annual Impact Report 2020 stressed the urgent need for collective action worldwide to create meaningful and sustainable change.

In addition to reduced plastics use, it says global solutions to address post-pandemic waste management challenges are needed. It cites the example of Indonesia, where business, government and civil society worked with GPAP to develop a plan to reduce the amount of plastic reaching the ocean by 70% within five years.

GPAP also says accelerated efforts to create a global circular economy are needed. This is echoed by the New Plastics Economy initiative, which calls for the elimination of all unnecessary plastics and further innovation to ensure those which are used are reusable, recyclable or compostable.

A circular economy – in which items are used, not used up – for plastic would keep the material in the wider economy and out of the environment. This, the initiative argues, would benefit the environment, society and the economy.

*Writer, Formative Content

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer