by Michael Spellacy, Alan McIntyre and Derek Baraldi*

The fallout from COVID-19 continues to challenge and disrupt economies around the world, but the banking and capital markets sectors can help steady the ship. Through new, innovative liquidity plays, they can support small and medium enterprises (SMEs), struggling industries, and emerging markets to ensure that all sections of the global economy emerge successfully on the other side of this crisis.

Banks and capital markets firms need to play a leading role in the three distinct phases of this rescue effort – the sovereign phase, the debt phase, and the equity phase. Government support in many countries is likely to taper off this autumn, whereupon we will increasingly see economies transitioning into phases 2 (debt) and 3 (equity). During the debt phase, banks and fixed income investors will bear the primary burden of providing capital and liquidity. Whereas private investors and public capital will be the main players in the equity phase, when businesses, unable to service their debt, will need to be restructured and recapitalized.

Financial institutions that participate in both phases 2 and 3 will need to think beyond short-term shareholder returns and take a “big picture” approach – finding opportunities that can benefit the wider economy while making smart, responsible bets for long-term growth.

Dealing with debt

During the debt phase, financial institutions will initially need to evaluate the landscape by reviewing their existing credit book to understand their levels of exposure across different sectors, and proactively identifying where new credit is needed.

As they begin to extend debt, they’ll need to spread their risk among different credit businesses while continuously checking for viability and assessing their credit capacity. They’ll need to set criteria to decide who should get relief and who needs to be restructured, which will prevent the rise of zombie corporations that are allowed to stagger on when it would be in the broader societal interest for them to default and restructure. This will require a delicate balancing act as financial institutions will need to identify the true strugglers, while still striving to be fair and equitable.

During the first phase of economic stabilization, the banking sector, in addition to offering standard debt vehicles, has largely acted as a conduit for the central banks’ guaranteed loan programmes for SMEs. However, bank lending has remained limp since the 2008 financial crisis as a result of uncertainty, regulation, and monetary policy, which means that they’re not the market’s panacea when it comes to smoothing the passage of loans, even if they’re backed by the government. That has provided an opening for the shadow banking industry – capital markets players, including private equity – to increase their direct private lending, either in the form of debt restructuring or bridge financing. In markets like the US, direct lending by institutional credit funds has become a powerful force in SME lending and in some recent time periods the majority of credit extended has come from these sources of capital.

In phase 2, fewer loans will be backed by the government, so the industry has to walk the tightrope of balancing relief with financial responsibility. That will be especially true when it comes to dealing with struggling sectors. This is when Banking and Capital Markets players will need to be extra vigilant of economic indicators to constantly re-assess the depth of the crisis and their capacity to extend new debt to borrowers who are teetering on the edge of medium-term viability.

Businesses in industries including travel, automotive and energy are currently seeking new lines of credit, and once the public and banking sectors have reached certain thresholds, we will see capital markets players step in to offer direct lending and other forms of debt. We are already seeing an expansion of full balance sheet solutions for some of these troubled industries with innovative sale and leaseback, or financial engineering solutions that allow struggling businesses to access their full capital base to generate much needed cashflow.

Roger Bieri, Head of Multinationals Clients at UBS, says: “The first thing that we focus on is trying to understand if a company is a designated survivor, i.e. has the company performed well before the crisis, and does it has a business model that is future-proof? If the answer is no, we help these companies, together with external advisors, to review their business model and potentially restructure the business and/or find new investors."

Needed: creative equity solutions

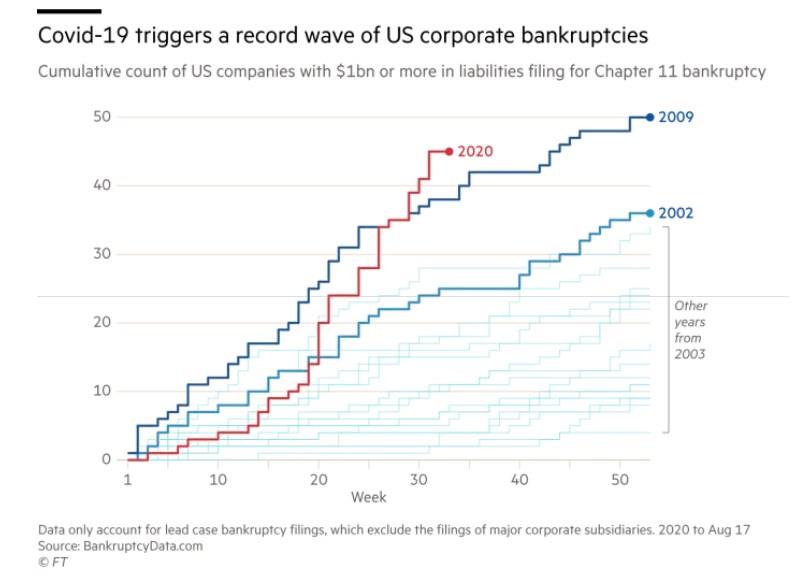

For many businesses, getting to the other side of this pandemic will require more than credit. In the US so far this year, 45 businesses, each with over $1 billion in liabilities, have already gone bankrupt. That number could double by the end of the year. In the small and medium-sized business sector, 50% of companies now consider themselves under severe financial strain and millions have indicated they may have shut their doors for good. To help these struggling businesses, the banking and capital markets industry will need to find creative, versatile solutions in the equity phase. These solutions will need to smooth the transition from phase 2 to 3 and benefit a large segment of struggling entities, from large companies and developed nations, to smaller businesses and emerging markets.

Bernie Mensah, President of Bank of America’s International Bank, says: “Our capital markets colleagues are having a whole bunch of conversations with eligible borrowers about structures that give them access to the liquidity that is there and typically, you’ll see innovative structures.”

They will make use of three traditional equity vehicles. The most disruptive is bankruptcy and recapitalization, where existing shareholders are wiped out and new capital repurposes assets. The second is new equity injections from either private or public sources, typically in preferred structures that give the new investors more of the upside. The third option is converting existing debt to equity in order to strengthen company balance sheets and improve available cashflow. Through this process, lenders (both public and private) become owners.

This crisis presents a unique opportunity for the capital markets sector, especially considering the $1.6 trillion of dry powder available to private equity and the continued balance sheet strength of players like JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs. Where private investors are unwilling to step in, we are already seeing public capital fill the void. For example, the German government stepped in with an equity injection to save the airline Lufthansa. While these interventions can protect jobs in the short-term they do highlight one of the potential risks of private capital sitting it out: the rise of economic nationalism to tilt the playing field in favour of businesses in which the state has a stake.

With falling valuations and low interest rates, the current conditions present an attractive opportunity for private investors. However, being an active player during a period of restructuring will require the banking and capital markets industries to innovate and find new ways to reach deeper into severely affected sectors and go beyond the highly visible large corporate sector to support and reshape the SME sector that accounts for the vast majority of employment in most economies.

Finding solutions for smaller businesses

Banks and capital markets have devised equity restructuring solutions before, but they’ve never had to deal with the scale of challenge that this crisis presents. This moment calls for the creation of new asset classes that can attract capital while ensuring that the impact of that capital is broad based. For example, investors could take direct equity stakes in large corporations that supply liquidity to SMEs through trade credit. Or they could invest directly in SME-focused exchange traded funds (ETFs). Additionally, private investors and private equity firms could provide lower-risk liquidity for SMEs by taking minority stakes in businesses, which lessens the valuation sensitivity and reduces the risk of ownership by maintaining existing shareholder control. There is also a role for the public sector in making SME equity investments attractive by changing the tax treatment of returns, or providing matching funds through business development schemes.

In all of these cases, investors will need to stump up the necessary short-term liquidity to mitigate the hit of the crisis, while accepting that their equity returns might be a long game. But structured correctly, pension funds and other long-term investment vehicles might be the “patient capital” required to support local community businesses.

This solution could support struggling sectors as well. For example, independent businesses operating in the same sector could join forces to form networks that enhance purchasing power and share back-office support functions. Cross-sector groups could leverage community investment funds that offer industry expertise to make smart investment decisions. The alternative is a solipsistic and fragmented landscape of narrow self-optimization leading to bankrupt businesses and shuttered communities.

Simi Siwisa, Head of Public Policy at Absa Group, says: “Banks want to finance and spur growth because we understand the responsibility, but even some of our clients are saying the outlook does not look positive and some will not be investing until confidence returns. It’s almost like a circular pattern, you had COVID-19, you had the lockdowns, declining economic growth, collapse in global trade, collapse in confidence, so who blinks first? Do banks extend credit? Or does industry decide to reinvest? I think there’s a balance there somewhere and understanding it and finding it is key.”

Helping in emerging markets

Banks and capital markets players will also need a strategy for emerging markets, where, traditionally, the only restructuring route has been bankruptcy. In the equity phase, investors will need to develop solutions and products that can support entire ailing sectors, rather than just individual companies, such as a quasi-equity fund that invests in smaller companies and has less regulations. Or blended finance options that provide much-needed financing without affecting the stability and resilience of the financial sector.

These solutions will have to keep the threat of economic nationalism in check while finding ways to encourage purpose-driven banking. Solutions here could mirror those for the SME sector including direct investment in ETFs or foreign corporate bonds. Firms could also take direct equity stakes providing they account for the tough regulatory environment they could be facing.

The Banking and Capital Markets community can’t simply sit this one out. Mensah explains that anaemic global growth over the last two decades is a symptom of emerging markets malaise. The US simply cannot grow at a 3-4% clip if the BRIC economies are faltering. The banking and capital markets industries have a call to action – one that asks for industry support for SMEs, emerging markets and struggling sectors with new, revamped debt and equity plays. This way, it won’t just be large corporations and developed markets that weather the storm and emerge successfully, instead there will be clear-sighted but broad-based economic support.

Whether the credit crisis will turn into a full-blown solvency issue for the banking sector is still unknown. But what we do know is that the banking and capital markets industries have the opportunity to be change agents in how the world can restructure for growth.

*Senior Managing Director, Global Capital Markets Lead, Accenture and Senior Managing Director, Global Banking Lead, Accenture and Head of the Banking Industry, World Economic Forum

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer