by Bjorn Andersson*

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced a glaring truth about gender-based violence: it is a humanitarian, development and socio-economic crisis; a persistent and daunting triple threat whose solutions must be grounded in gender equality and human rights.

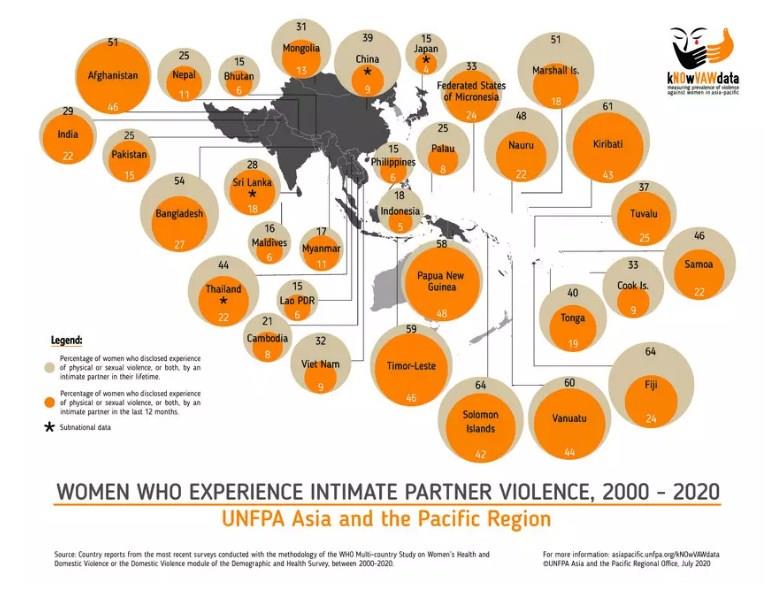

Even before the pandemic, gender-based violence was a debilitating challenge globally, with an average of one in three women experiencing some form of violence in her lifetime. In Asia and the Pacific, the percentage of women disclosing experience of physical or sexual violence – or both – by an intimate partner ranges widely between different countries. In Lao PDR and Japan, it’s 15%; several Pacific countries, like the Solomon Islands and Fiji, it’s 64%.

Not long after the WHO declared a COVID-19 pandemic in March, UNFPA forecast that an estimated 31 million additional incidents of gender-based violence could be expected globally if lockdowns were to last for at least six months, with women confined indoors with their abusers. For every three months that such restrictions continue, an additional 15 million incidents could be expected.

We’ve already seen huge spikes in the numbers of women seeking support, including through calls to dedicated helplines. The resources available to address gender-based violence, already stretched thin in many places before the pandemic, are all the more challenged now. We know that this escalating violence will have long-term and damaging socio-economic consequences for women’s health, safety, security and economic participation.

Another truth uncovered by the pandemic is that responding to gender-based violence in the context of unprecedented challenge requires creativity, collaboration and courage – as displayed by the humanitarian heroes supporting survivors in so many different ways in country after country, no matter how difficult the circumstances.

In Nepal, teams of community psychosocial workers, already present in remote far-western and eastern rural districts before the pandemic, are being given additional air-time on their mobile phones to increase psychological first aid and referral support to survivors, connecting them to locally available services. Saraswati Rai Chaudhury and her colleagues roam far and wide to also reach migrant workers in quarantine centres, mothers’ groups and their children, relatives of COVID-19 patients and elderly people. Since Nepal’s lockdown began, more than 4,500 women have been assisted.

For Rohingya refugees in the sprawling camps of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, service providers have expanded the support available in women-friendly spaces to include midwives, like Tania Akter, alongside psychosocial counsellors, integrating essential gender-based violence and sexual and reproductive health services under one roof. A huge proportion of those contracting COVID-19 worldwide have been frontline health workers like Tania who put themselves at risk, working long, gruelling hours to meet demand and needs, while being away from their loved ones for months on end.

In Myanmar, realizing there is a crucial need to scale services, government, civil society and UN partners came together to boost helplines by training responders to provide immediate, remote psychological first aid. Callers can also be directed to women support centres that are safe spaces and link women to various types of assistance. Elsewhere, many health actors have been trained and mobilized to support survivors.

After earthquakes struck the Philippine province of North Cotobato last year, local organizations established evacuation centres that included timely and quality care as part of gender-based violence response services. This helped women navigate the local system to seek life-saving support. With this support extending into the pandemic, dozens of Filipino women are now benefitting through these centres from a new initiative called Cash for Protection, which provides 10,000 PHP (~$200) as part of a wider social safety net for survivors.

In Rawalpindi, Pakistan, the Women Safety smartphone app, introduced two years ago, was urgently upgraded by the Punjab Safe Cities Authority (PSCA) earlier this year as pandemic lockdowns intensified. Women who install the app can alert the police on an emergency helpline or send a text via WhatsApp to the PSCA. As soon as the message with location coordinates is received, designated teams are mobilized for an immediate response, heading to the caller’s precise location.

We’ve learned useful lessons – and promising practices – from the numerous critical interventions led by humanitarian heroes like Saraswati, Tania and so many others.

1. Services to support survivors of gender-based violence are truly life saving and more crucial than ever. Governments cannot and must not compromise or sacrifice this support when funding the pandemic response; it’s a matter of life and death for thousands upon thousands of women and girls.

2. National governments must invest much more in gender-based violence prevention and response resources, including a skilled and empowered workforce of frontline service providers. This will build on a regional and global evidence base of what works to create a strong foundation so that this life-saving work can be quickly expanded during emergencies like COVID-19.

3. Necessity is indeed the mother of invention. Some of the most effective interventions we’ve seen embrace creative thinking despite COVID-19-related restrictions and have adapted user-friendly technology to reach gender-based violence survivors safely. Partnerships between government, civil society and the private sector are vital to ensure we innovate to reach the most vulnerable and marginalized.

4. Countries can and should learn from one another by sharing what works.

We’ve heard a lot about the post-COVID-19 need to “build back better” to ensure no one is left behind. To convert rhetoric into reality, we must all prioritize the health and well-being of women and girls, from achieving optimal sexual and reproductive health to ending gender-based violence and harmful practices – starting now.

*Asia-Pacific Regional Director, United Nations Population Fund

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer