by Ankita Sharma and Hindol Sengupta*

Since the beginning of its COVID-19 lockdown in late March, India has distributed around $5 billion in cash benefits to its citizens who need assistance the most, entirely through payments made via digital platforms.

The country was already on a digital-first trajectory with one of the highest volumes of digital transactions in the world when the pandemic struck, and further propelled the use of contactless digital technology.

Data from the apex Reserve Bank of India (RBI) show that India is now clocking around 100 million digital transactions a day with a volume of 5 trillion rupees ($67 billion), about a five-times jump from 2016. RBI expects this to further grow five-fold to 1.5 billion transactions a day worth 15 trillion rupees ($200 billion). Much of this is powered by the United Payment Interface (UPI), a real-time payment system developed by the National Payments Corporation of India and monitored by RBI.

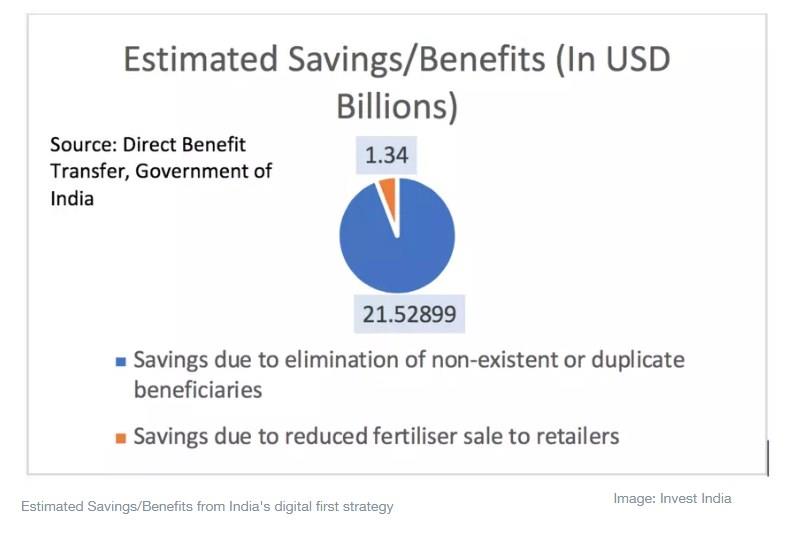

This digital-first reset of a country of 1.3 billion people is not only technological advancement but, more importantly, it is the foundation of a new mechanism for the deliverance of goods of governance. Embedded in this programmatic use of technology by the state are two promises which have historically been difficult to fulfil in India – speed and the plugging of leakages. The use of digital technology led to savings of nearly $23 billion, 98% of this by eliminating erroneous beneficiaries.

The digital reset of the Indian economy has seeped into almost every aspect of life. Almost every Indian now has the digitally authenticated Aadhar identification number. The connection of Aadhar with bank accounts (under a financial inclusion scheme called Jan Dhan), and mobile phones (India has more than a billion mobile phone subscriptions), or what has been called JAM, is the bedrock of much of this reset.

With the lockdown placing immense strain on the household budgets of several sections of society, JAM played the role of a safety net and helping millions who need immediate monetary aid through ubiquitous direct transfer of state benefits. Aadhar is also the base for India Stack, a set of open APIs (Application Programme Interface) which developers can use as the foundations for their applications.

And that is not all. To effectively track and monitor the spread of COVID-19, India’s National Informatics Centre created the Aarogya Setu app, which has been downloaded more than 127 million times. Its citizen participation and feedback platform MyGov.in has around 9.5 million users and gets 10,000 posts per week.

Aarogya Setu and other allied initiatives like the National e-Health Authority and new tele-medicine guidelines are coalescing towards a National Health Stack which is aimed to be completed by 2022. From filling healthcare needs in remote areas to building data-driven public policy on health, the use of technology fulfills many roles and most importantly in some of the most remote areas of the country.

Indian states used the COVID-19 opportunity to further spread the use of technology – whether it is use of Collaborative Robots (Co-Bot) by the government in the eastern state of Jharkhand or the municipal corporation of Bengaluru, India’s tech hub, using drones to spray disinfectants, survey areas, monitor containment zones and make public announcements.

Several other Indian states like Telangana, Karnataka, Gujarat and cities like Varanasi are using similar measures to combat issues arising from the pandemic. By using technology, the state governments are also managing the demand, availability and use of equipment like ventilators, as well as essential medical items, including N95 masks and personal protective equipment (PPE).

The use of technology is decentralizing decision-making, bridging communities with local governments across cities and towns. Using technology and digital tools, these innovative solutions are having an impact across various spheres of life, be it livelihoods, access to services or education. For instance, using aggregator apps, hyper-local vendors like those selling vegetables in neighbourhoods or plying e-rickshaws are now able to provide door-to-door services while receiving consolidated payments on a monthly basis – thus providing a stable source of income. Similarly, in education, many schools have shifted to online classrooms while students and educators with limited internet connectivity are also learning via mobile phones.

This rapid roll-out of state technological infrastructure, has triggered an equal response in private business. As the Indian government promotes DIKSHA, a platform for school education, and introduces training in coding at middle school level, the country has the world’s highest funded educated app, Bjyu’s, which has raised nearly a billion dollars, and Jio, an all-services tech platform, from Reliance, India’s most valuable company by market capitalisation, has raised $15 billion during the pandemic from a clutch of investors including Facebook, with the promise of delivering a digital lifestyle to every Indian.

To hasten the process of last mile connectivity of tech right up to the last consumer, Google has announced an additional $10 billion of investment in India in the next five to seven years – to provide internet access in every Indian language, and use technology in agriculture, education and health.

This joint public-private push is making India a digital-first country, resetting the basic life experience and aspirations of more than a billion people.

*Senior researcher, Invest India and Vice-President, Invest India

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer