by Anton Ovchinnikov*

Left to their own devices, humans tend to fall prey to biases that make them poor decision makers. For instance, among other foibles, most purchasing managers routinely under-order. In fact, past research has shown that managers are typically 10 to 20 percent off the mark when it comes to ordering the optimal quantity of products.

However, somewhat surprisingly, the same research has also shown that this sub-optimal ordering only results in a 1 to 5 percent loss in expected profit. This conundrum has left many an executive with a dilemma. As the CEO of a medium-sized online florist shop told me: “I cannot micro-manage all my people. Before I go and intervene, I need to know the impact on my business.”

Fair point. Managers who base purchasing decisions on their gut feelings – either because they have never devised a rational ordering policy or regularly choose to override it – make a lot of mistakes. But if it only costs the firm about 1 percent of extra profit, executives may be reluctant to stir the pot. In most SMEs, a CEO’s path is strewn with seemingly juicier projects in terms of ROI.

Such laissez-faire may be costlier than prior research had predicted. In the last 15 years or so, most academic papers on the so-called “newsvendor problem” examined profit maximisation in monopoly-like settings. But when Bernardo Quiroga (School of Management at PUC Chile), Brent Moritz (Smeal College of Business at Penn State) and I looked at what happens in a more realistic context involving competition, we found that a firm could increase its profit by 7 to 10 percent by adopting a scientific approach to ordering.

Delivering your customers on a silver platter

In our recent paper, “Behavioral Ordering, Competition and Profits: An Experimental Investigation”, we used controlled laboratory experiments to replicate a market with two competitors: a smart one with a data- and science-driven ordering policy in place and another leaving its ordering in the hands of a capable but inevitably biased manager.

In our experiments, a computer played the role of the smart firm. It followed simple ordering rules steeped in management science. Business school students played the role of the competitor. While our participants were given full access to market data, they could order as they saw fit, leaving the door open to all the biases known to affect managers in this situation. (Of course, we used cash to incentivise them to make the very best inventory decisions possible.) We found that the average expected profits of our smart firm were 15 to 20 percent larger than those of its human-bias-riddled competitor.

What explains this large profit difference? As mentioned, a common trait of purchasing managers is their tendency to under-order. So what happens when customers come to your shop and cannot find the specific product they wanted to purchase, say red roses? While they may buy a substitute product (e.g. pink roses), odds are that they will walk themselves out the door to your nearest competitor.

If a competitor consistently outperforms you in stocking products and anticipating demand, even the most loyal of your customers may desert you over time, boosting your competitor’s bottom line.

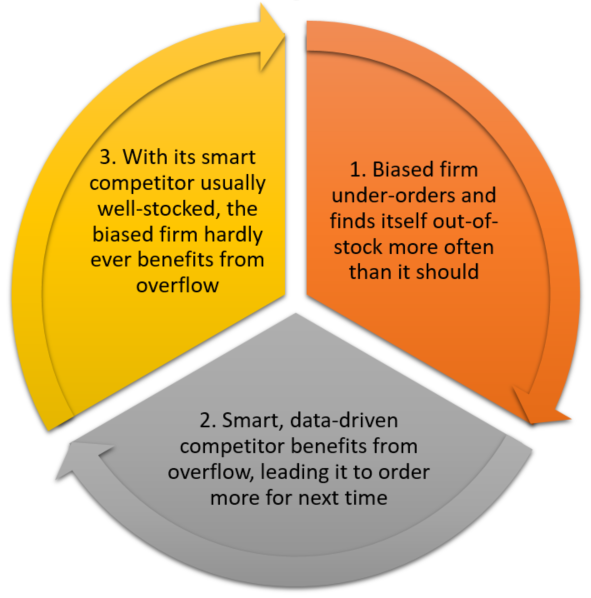

These competitive dynamics are self-reinforcing, as shown in the following schematic:

Are you always one step ahead or behind?

Thanks to past management literature, we know quite a bit about the particular quirks of managers who find themselves in the newsvendor paradigm. Not only do they routinely under-order, but they also lack responsiveness to situations calling for a change in purchase order size (“pull-to-centre effect”) and are likely to mindlessly adjust order quantities based on past demand (“demand chasing”). In other words, even in the absence of competition, managers, prey to various psychological biases, leave money on the table despite trying to maximise profit.

In a previous paper, also co-written with Quiroga and Moritz, we found that purchasing managers who know exactly what the competition is ordering are hardly influenced by this information. Even if they see that their competitor has a sophisticated ordering model that results in an outsized share of profit, they do not respond. They get trapped in the self-reinforcing dynamics illustrated in the figure above. As the competitor usually captures the overflow, the manager of the biased firm sees even less reason to order more. The smart competitor is, in effect, always one step ahead.

Watch out for biases

In economics, the newsvendor model is typically cast as a vendor selling perishable inventory, but it is, in fact, a metaphor for decision making with uncertainty. It applies to any decision that must be made in the moment, based on historical data that may not hold true in the future. It could be a firm trying to assess how many solar panels to install on its roof, without knowing what the demand and prices of electricity will be. Alternatively, it could be a carmaker anticipating sales to best design its manufacturing platforms.

Our work shows that a knowledgeable firm applying ordering policies based on sound management science can significantly outperform its competitors across three metrics: service, market share and, most importantly, profit. Over time, a firm benefitting from such an advantage could further improve its business well beyond inventory-based competition alone. For instance, it could afford more aggressive advertising, expand into new markets or even win talent wars.

The message should be clear to all CEOs relying on the intuition of their managers: Profit losses stemming from managerial biases are substantial enough to warrant your attention.

*Visiting Professor of Decision Sciences and Technology and Operations Management at INSEAD and a Distinguished Professor of Management Analytics and Scotiabank Scholar of Customer Analytics at Smith School of Business, Queen’s University in Canada.

**first published in: knowledge.insead.edu

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer