by Eugenia Rossi*

While some legal and policy advancements signal progress, new challenges cast a shadow over past achievements. From Europe to the United States, recent setbacks raise urgent questions about how much real progress has truly been made – and how easily it can be undone.

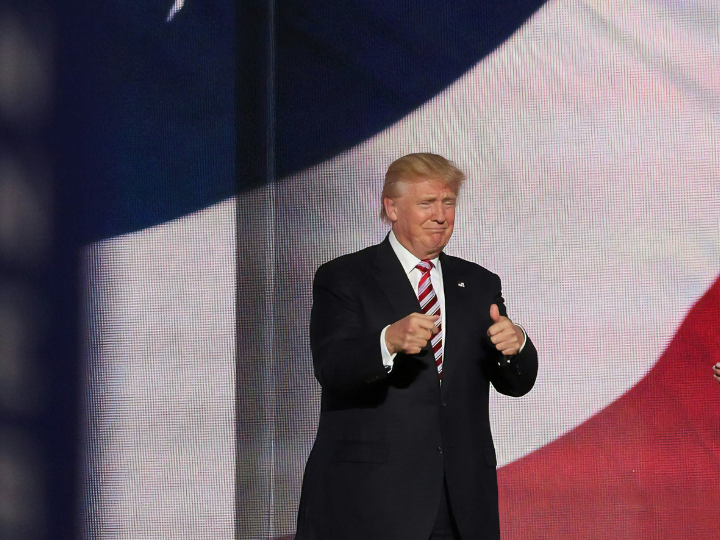

In the US, the new administration has taken steps that risk reversing decades of progress on gender equality. Trump’s policies not only jeopardise women’s rights domestically, but also threaten global advancements: cuts to US development, humanitarian and medical aid have already had severe consequences for women and girls facing violence, conflict, disasters and disease.

Europe is not immune. In Germany, a telling picture of the presumptive next Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s all-male transition team has reignited debates about gender representation in politics, which is less straightforward than one might think.

Roughly a century after women started to obtain the right to vote, they remain underrepresented in politics and public life. This imbalance is evident across the European Parliament, national legislatures, governments and local assemblies.

This issue goes beyond women, affecting all marginalised groups who, despite having legal equality in most advanced democracies, still face systemic barriers – showing that equality on paper does not always mean fairness in practice.

It is not surprising, then, that statistics on gender perceptions reflect these biases. The latest 2024 Eurobarometer survey found that nearly half of respondents believe men are more ambitious in politics than women, highlighting the deep-rooted stereotypes that continue to influence political life.

The persistence of these disparities is particularly concerning given the clear benefits of gender diversity in leadership. Research has shown that long-term efforts towards diversity, equity and inclusion lead to increased productivity, better adaptability and stronger innovation. In a competitive economic and political environment, gender parity should be seen as an advantage, not a concession. Yet, the risk of backsliding remains, raising urgent questions about the future of women’s rights.

A fundamental starting point in discussing women’s role in politics is the distinction between descriptive and substantive representation. Political theorist Hanna Pitkin defined substantive representation as acting in the interest of those they represent in a responsive manner. Applied to women, this means ensuring that female citizens and their concerns are central to policymaking. Descriptive representation, on the other hand, refers to the presence of women in political positions, ensuring leadership reflects the gender composition of society. While both forms of representation are important, one does not automatically lead to the other.

While there appears to be some connection between having more women in office and advancing women’s interests in policy, several prominent women in Europe’s conservative movements clearly challenge this link.

These figures are often highly visible, appearing prominently in political discourse and media coverage. Alice Weidel, leader of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), represents a party that has consistently opposed feminist policies and gender equality initiatives.

Giorgia Meloni, despite breaking barriers as Italy’s first female Prime Minister, largely upholds traditional family values rather than advocating for progressive gender reforms. French politician Marine Le Pen presents herself as a strong female leader, but her party remains largely conservative on gender issues, prioritising national identity over women’s rights. Beata Szydło, during her tenure as Poland’s prime minister, supported policies that reinforced traditional gender roles and restricted reproductive rights.

If we focus only on descriptive representation, the increasing presence of women leaders in conservative politics might seem like progress. However, this perception does not reflect a broader shift: conservative parties do not elect more women than left-wing parties; rather, a few high-profile female leaders create the impression of greater female political representation.

A comprehensive study by Diana Z. O’Brien examining women’s representation in parliamentary democracies since 1980 found that right-wing parties generally lag behind their leftist counterparts in regard to descriptive representation.

Moreover, conservative parties are less likely to prioritise women’s rights in policy. Compared to left-leaning parties, they are less supportive of measures such as access to abortion, protections against domestic violence and workplace gender equality. Instead, their references to women often align with conservative ideals, focusing on family and motherhood rather than independence and empowerment.

This brings us back to an important question: what exactly are women’s interests? Female politicians may advocate for women, but their vision of women’s needs is shaped by their political ideology. Women in power often push policies they believe are beneficial to women, but these policies can take vastly different directions. For example, while some see access to abortion as essential to body autonomy, others view restricting it as a way to protect women and the family unit.

Ultimately, achieving true substantive representation requires an evolving and inclusive vision of gender equality – one that extends beyond simply electing more women to positions of power.

Furthermore, even when conservative women in politics support women’s rights, their approach can be problematic if it excludes certain groups. A key example is Kemi Badenoch’s announcement that the British Conservative Party would redefine sex in the Equality Act to mean “biological sex”. This change would allow organisations to bar trans women from single-sex spaces such as hospital wards and domestic abuse shelters. While framed as protecting women, this stance would marginalise trans women, highlighting how some conservative-backed women’s rights policies can reinforce exclusion rather than inclusion.

It is clear that advancing gender equality requires both descriptive and substantive representation, but how can this be achieved?

On the one hand, while not sufficient on its own, boosting women’s political participation is vital, and gender quotas remain one of the most effective tools to achieve this. According to the latest Eurobarometer, a majority of EU citizens support temporary measures such as quotas to address women’s underrepresentation. The European Parliament has attempted to push for reforms requiring member states to enforce gender equality in European elections, but progress has stalled.

The struggle for a female UN Secretary-General exemplifies the need for clear rules to put women in leadership, rather than relying on voters to overcome gender bias. Despite a 1997 UN resolution supporting gender balance in leadership and the UN’s global efforts for equality, no woman has ever led the UN. Civil society campaigns advocating for a woman to succeed current Secretary General António Guterres may not be enough. This highlights the need for binding measures, such as quotas, alongside broader changes to shift leadership structures and perceptions.

Institutional structures also play a key role in shaping political participation. Electoral systems can either facilitate or hinder women’s involvement in politics. For instance, multi-seat constituencies tend to be more favourable to female candidates than single-member district systems, which often reinforce male dominance.

Governments can also create a more supportive political environment. In countries like France and Portugal, regulations linking public funding to gender equality within parties have strengthened women’s political roles and contributed to significant increases in female parliamentary representation.

Media coverage plays a crucial role in shaping women’s political representation. In traditional media, female candidates often receive less attention, limiting their visibility and electoral prospects, and, while social media provides a direct platform for communication, it also exposes female politicians, especially those advocating for women’s rights, to widespread misogynistic abuse. A survey by the Inter-Parliamentary Union found that social media has become the primary space for psychological violence against women in politics.

This troubling trend highlights the urgent need for stronger measures: more balanced coverage in the news can encourage female political participation and digital platforms must prioritise safer online spaces. Unfortunately, recent trends in social media governance, particularly under Donald Trump’s influence, have moved in the opposite direction.

On the other hand, substantive policies that directly impact women’s lives are crucial. One key area is reproductive health, which should not be treated as a political battleground but rather as an integral part of universal healthcare. Establishing EU-wide minimum standards for access to contraception and abortion would help ensure that women’s rights are not subject to the shifting priorities of national governments. Without such safeguards, reproductive healthcare remains vulnerable to political shifts, leaving women’s autonomy at risk.

Another essential approach is gender mainstreaming – the integration of gender perspectives into all areas of policymaking. This means that gender equality is not treated as a separate issue but embedded in economic, social and security policies. From budget allocation to labour laws, and from education to climate policies, decision-makers must consider how policies affect men and women differently. Only by making gender equality a fundamental principle of governance can real progress be made.

Achieving substantive representation also requires a commitment to policy change at every level. It is not enough to elect women to high office; political institutions must be designed to support equality through legislation, funding and enforcement mechanisms. The question remains: will governments take the necessary steps to move beyond symbolic gestures and create lasting change for women?

Ultimately, we can see how the rise of female leaders in Europe’s far-right movements highlights the complexities of gender representation in politics. While their presence challenges traditional male-dominated leadership structures, it does not automatically translate into substantive progress for women’s rights. Encouraging politicians who champion these causes and ensuring that gender equality remains a policy priority are essential steps forward.

As we consider how to improve women’s representation, we must also take into account that efforts to promote gender equality often provoke backlash. Conservative forces may become more radicalised in response, seeking to undermine progress through legal and cultural resistance. Addressing this challenge requires not only legislative action but also a broader societal shift – breaking down entrenched stereotypes and fostering an environment where women can thrive in leadership roles with real influence.

Moreover, representation is not a one-size-fits-all solution. The inclusion of privileged women risks reinforcing existing inequalities, rather than dismantling them. Do women from different backgrounds – including those shaped by race, class and sexuality – have equal access to representation and influence?

The case of Alice Weidel, the openly queer leader of Germany’s far-right AfD, raises further questions about intersectionality. Her leadership challenges stereotypes about the party’s social conservatism but does little to advance LGBTQAI+ or women’s rights more broadly. What does this tell us about the limits of representation in addressing deeper social inequalities?

Ultimately, it is not just about who holds power, but how that power is used to create a more just and equitable society.

*Programme Assistant at Friends of Europe

**first published in friendsofeurope.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer