by Fleming Voetmann*

Europeans spend 90% of their time indoors and yet, one in four live in buildings where indoor air quality falls below national standards, while over 30 million live in buildings that are too dark.

Inefficient thermal building envelopes also make maintaining an appropriate indoor temperature difficult.

While Europe is known as a leader in sustainable building design, improving indoor air quality, energy efficiency and exposure to natural light remain significant challenges even when resources are relatively abundant.

These inadequate living and working environments can negatively affect physical and mental health, impacting concentration and performance. These are some of the Healthy Buildings Barometer 2024 findings, researched and written by Buildings Performance Institute Europe for the VELUX Group.

Building policy should centre on ensuring buildings are healthy and supporting the well-being of those who inhabit them.

Filling a data and knowledge gap

The 2024 Healthy Buildings Barometer is the eighth edition of the Healthy Homes Barometer, which has tracked the state of European Union (EU) homes since 2015. The initial intention for the barometer was to gather the data needed to understand the impact of buildings on health and well-being.

Anecdotally, the link has always been clear for anyone who has spent time in a room without sufficient access to fresh air and daylight – however, the hard data to back this link and the business case for better ventilation.

This year, the report focuses on all major building types, not just homes. It includes a comprehensive framework to define a healthy building alongside policy recommendations to achieve one.

For example, the report’s findings show that greater exposure to daylight improves performance by as much as 10% in workplaces and 9-18% in schools. Meanwhile, every 1-degree reduction in overheating enhances performance by up to 3.6% in the workplace and 2.3% in schools.

The report also highlights the economic benefits of addressing unhealthy buildings. Costs of renovating all inefficient buildings in the EU could take just two years to recover and save €194 billion in equivalent societal benefits, such as fewer sick days and higher performance in the workplace and classrooms.

The critical need to drastically reduce carbon emissions is beyond quantification.

An actionable framework

Putting people at the centre of the clean energy transition is not only a way to gain public acceptance, but it also makes sense from a health, climate and financial perspective. So, how do we go about it?

Firstly, we need a standard definition of a healthy building.

The Healthy Buildings Barometer provides a multidimensional and actionable framework that integrates health, buildings and climate into a new definition of healthy buildings.

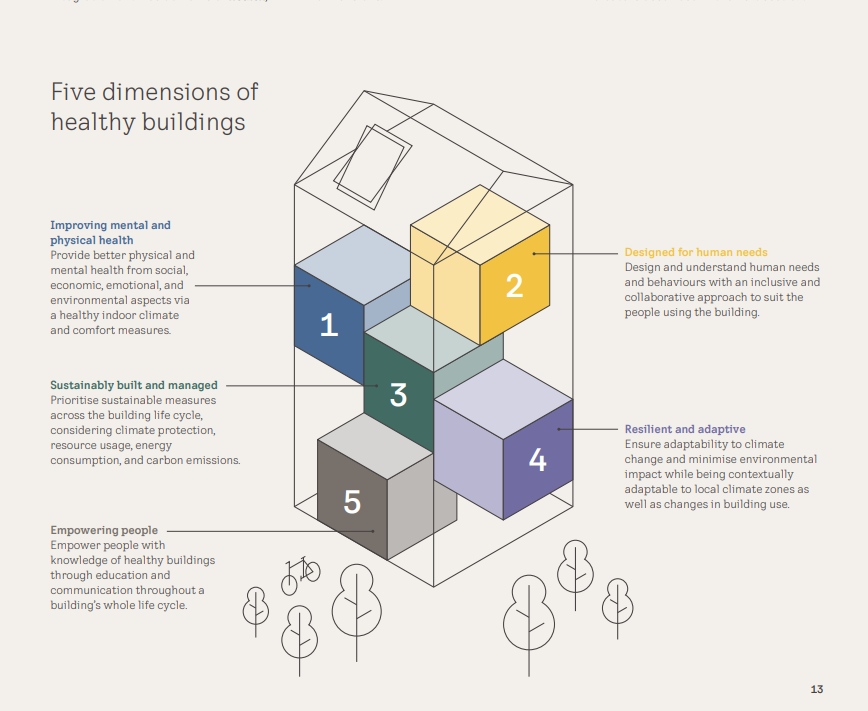

These three domains are enacted through five dimensions, which allows stakeholders the required guidance and framework for integrating them, applicable to new-build and renovated buildings:

-Improving mental and physical health.

-Designed for human needs.

-Sustainably built and managed.

-Resilient and adaptive.

-Empowering people.

Image: VELUX Group

People-centred recommendations

So, what are the next steps? The Healthy Buildings Barometer proposes a series of recommendations based on three key ideas anchored on a people-first approach to the climate transition, which may be acted on via a multistakeholder collaborative approach.

1. Accelerate adoption of a comprehensive definition and framework of healthy buildings to drive progress.

Healthy buildings cannot be understood by focusing exclusively on one characteristic, e.g. energy or decarbonization. Multifaceted interrogation can happen once a standard definition is agreed upon with policy measures that enable a holistic approach.

2. Prioritize high-quality data that tracks building health and occupant well-being

Data on buildings is often unavailable, incomplete or is measured irregularly, while data on building occupants are primarily associated with residential buildings.

Addressing the resultant gaps necessitates consensus on relevant data points for cross-functional collaboration and information-sharing between actors within and outside the construction sector i.e. everyone would be able to access comparable data.

3. Integrate health, sustainability and resilience into building policy

Policies and regulations that integrate a multidimensional focus on health, sustainability and resilience as key components of decision-making processes must be introduced.

What next?

The EU is off track in reaching the 2050 decarbonization objectives of the Paris Agreement regarding increasing energy efficiency and accelerating renovation rates.

However, the focus on buildings is growing at a European and international level. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the new Labour government has pledged to create another 1.5 million dwellings, while there will be a commissioner for energy and housing in the EU for the first time.

The Buildings Breakthrough was launched last year at the 2023 UN Climate Conference (COP28), followed by the inaugural Buildings and Climate Global Forum in Paris in March. This forum brought together stakeholders from across the building value chain at the ministerial level.

This convening led to the Chaillot declaration, with representatives of 70 countries agreeing to international cooperation to progress towards a rapid, fair and effective transition of the buildings sector.

While this is an important development, change requires even more collaboration between private and public partners, focusing on city- and local-level action, including neighbourhood-scale retrofits.

Such action is important because local governments are invariably the “first responders” with the most knowledge of local issues, traditions and challenges. Not least, they have the power to execute on ambition.

*Vice-President, External Relations and Sustainability, VELUX

**first published in: Weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer