by Denis MacShane*

It took many weeks, but France may at long last finally be on the road to having a government.

French politics divided into thirds

The goal is to try to establish a functioning government to emerge after Macron’s folly of dissolving the National Assembly. The result was like the structure of Caesar’s Gaul — French politics divided into thirds.

The left, the right and oddball center covering Macron’s own party all emerged from the National Assembly elections, but none of them had a majority to govern. And none of the three political blocks would tolerate compromise.

An alliance against nature

Under the banner of the New Popular Front, France’s left won the biggest number of seats in the French Parliament. But this grouping is an alliance against nature.

It is headed by the Trotskyist antisemitic demagogue Jean-Luc Melenchon, who operates in a loose alliance with French socialists left-over from the Mitterrand era and last in government 2012-17 under Francois Hollande plus remnants.

It also includes the once-mighty French Communist Party — as well as France’s Greens. One thing it is not: A unitary party.

Truth be told, the Socialists and Melenchonites no more belong in the same party than did Jeremy Corbyn and Sir Keir Starmer in the UK at the time or Yanis Varoufakis and Greek democratic socialists in Athens.

Indeed, all of the New Popular Front’s top political figures are waiting to see when they break apart in order to run separately in the 2027 French presidential race.

The Le Pen family party

The extreme right has slightly fewer seats than the left. The Le Pen family party was once called the National Front under its founder the antisemitic racist Jean-Marie Le Pen. Under his daughter, Marine Le Pen, it is now known as the National Rally.

Madame LePen has the French franchise for the 21st century anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, anti-European, pro-Putin, new populist identity nationalist politics.

It is the same brand seen in the United States with Trump, in Italy with Meloni, in Germany with the AfD, in England with the Reform party and the Braverman wing of the Tory party. There are variations in many countries.

LePen’s were clipped in the recent parliamentary elections when, thanks due political maneuvering in the anti-LePen block of French politics, her party won fewer seats than Melenchon.

In the middle: The Renaissance party

In the middle of French politics is the Renaissance party. It was set up by Macron as his personal vehicle for giving him a parliamentary majority to pass laws.

A French president is in charge of defense, wars and foreign policy, but on the whole leaves domestic legislation to the National Assembly, the Prime Minister and the usual ministers.

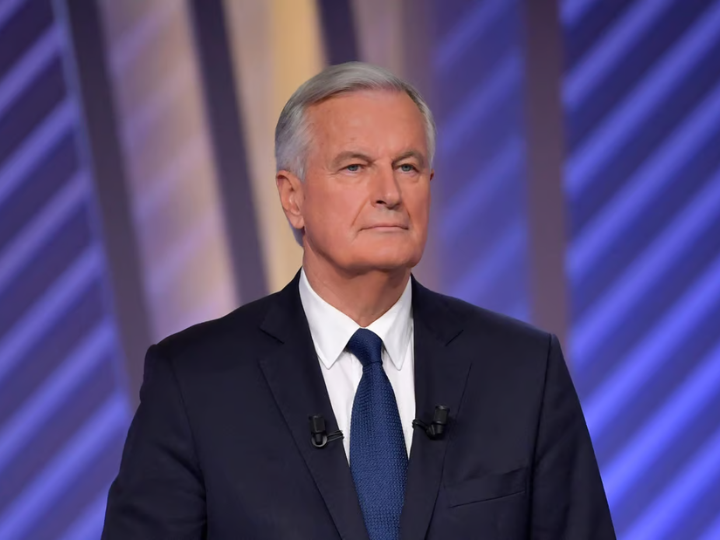

Enter Michel Barnier: Impressive track record

The challenge for Macron — and, effectively, all of French politics — was and is how to come up with a candidate for Prime Minister who could credibly work across entrenched partisan lines.

Barnier fits that bill. In a long career, he has worked with all political tribes. He has a bust of General de Gaulle in his study and always told me he was a “social Gaullist.”

He rose to fame as a local politician in his native Alpine region of Haute Savoie when he organized the successful Winter Olympics in 1992.

He was a European Commissioner for the Regions and then Foreign Minister under President Jacques Chirac. As the UK’s Minister for Europe, I worked with him during the last period in which a British government took Europe seriously.

A truly nice and competent colleague

Barnier kindly offered me lifts on his ministerial jet to meetings we both had to attend. I confess that I enjoyed the high-quality French cuisine which the French state provides for its ministers — a stark contrast to the Ryanair sandwiches offered by my home country’s parsimonious Foreign Office.

We kept in touch. When he took over the Brexit negotiation portfolio for the EU, we regularly met in Brussels or Paris, as I reported on the Brexit state of play in London politics.

Down-to-earth Michel Barnier ignored the bombast of Boris Johnson and the boasts of David Frost. He succeeded in giving Europe a ring-fenced deal that offered no concessions to the vanity of the Brits. The latter seriously thought the EU needed the UK more than Britain needed trade and access to Europe.

Can Barnier work his magic?

Now, Michel Barnier has to see if he can find a majority for the laws that France needs passing to be governed.

In a country not accustomed — indeed abhorred by the notion of cross-party coalition politics — that is a big task.

The early reactions of the others

Marine Le Pen has indicated to wait for the program proposed by Barnier before she takes a position on a vote of no confidence.

For his part, Jean-Luc Melenchon — head of the radical “France Unbowed” party — has chosen to play the classic Trotskyist equivalent of a leftist rejection of any laws proposed by a “bourgeois” prime minister.

Barnier does not have a majority in the French parliament. What further complicates his task is that Emmanuel Macron himself is without any experience of parliamentary politics or coalition formation.

Neither is Macron accustomed to work with anyone who is not a Oui-man or woman.

Barnier’s skill and advantage

Thankfully, Michel Barnier is Monsieur Compromise and France’s most experienced Can-Do politician.

In the end, the reality of French politics requires a change in the style of national leadership.

The fact that Barnier agreed to take the job is interesting in itself. He has not failed in any of the big jobs he has done for France.

To be sure, cleaning up the Augean Stables mess that Macron has created will be the biggest test that Michel Barnier has faced so far.

*Contributing Editor at The Globalist,UK’s Minister for Europe from 2002 to 2005,the author of “Brexiternity. The Uncertain Fate of Britain”

**first published in: Theglobalist.com

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer