by Bjorn Gillsater*

In Isabel Allende’s book A Long Petal of the Sea, the main protagonist is rescued, along with 2,000 other refugees, from the Spanish Civil War on a boat bound for Chile. Despite “trial after trial”, he becomes a highly skilled doctor in his adopted country. This year’s World Development Report, which focuses on migrants and refugees, begins with a Parsi legend in which priests convince a local ruler to accept refugees because they “would dissolve into life like sugar dissolves in the milk, sweetening the society but not unsettling it”.

While both stories are fictional, life is full of real examples too. The recent film The Swimmers portrays two Syrian sisters who swam part-way across the Mediterranean, towing a boat full of desperate people with them. But while inspiring stories are a solid start, policy-makers need data and evidence upon which to base their decisions, especially on a topic with such widespread impact as forced displacement.

When I was asked to establish the World Bank-UNHCR Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement (JDC) in 2019, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) reported that 64 million people were forcibly displaced. To aid the response of policy-makers and programmers to this problem, our aim was to improve the collection, analysis, dissemination and use of socioeconomic data.

Four years later, forced displacement has only escalated, and the number of people forced to flee tops 110 million. As new displacements erupt in places like Ukraine and Sudan, other major ones, in West Africa and South America, continue. Most of us are powerless in the face of these disasters, but we can influence the response. JDC focuses on improving the data that policy-makers have so their response to forced displacement is based on fact, not fiction.

Since 2019, vastly more data has been made available about those forced to flee. Perhaps the most significant change that the JDC has made to the displacement data landscape was by brokering the global Data Sharing Framework Agreement. This agreement, signed by the World Bank and UNHCR in June this year, will allow data from both organizations to be shared between them, faster and safely.

Though this had already occurred in some countries, such as Jordan and Afghanistan, getting to those agreements was often time-consuming and cumbersome. The new framework will improve the responsiveness of programmes for forcibly displaced people and shorten the time it takes to generate evidence needed for policy reforms.

But what about those outside these two organizations? There is also a wealth of data on forced displacement that has and is still being made available to the broader community of policy-makers, practitioners and researchers.

The UNHCR microdata library, which was created and maintained with support from the JDC, now hosts more than 600 datasets. National statistics offices in Chad, the Central African Republic, Uganda, Ethiopia, Honduras, Djibouti, Peru and Kenya are extending their national censuses and surveys to include refugees or internally displaced people, and providing the resulting data to policy-makers in those countries.

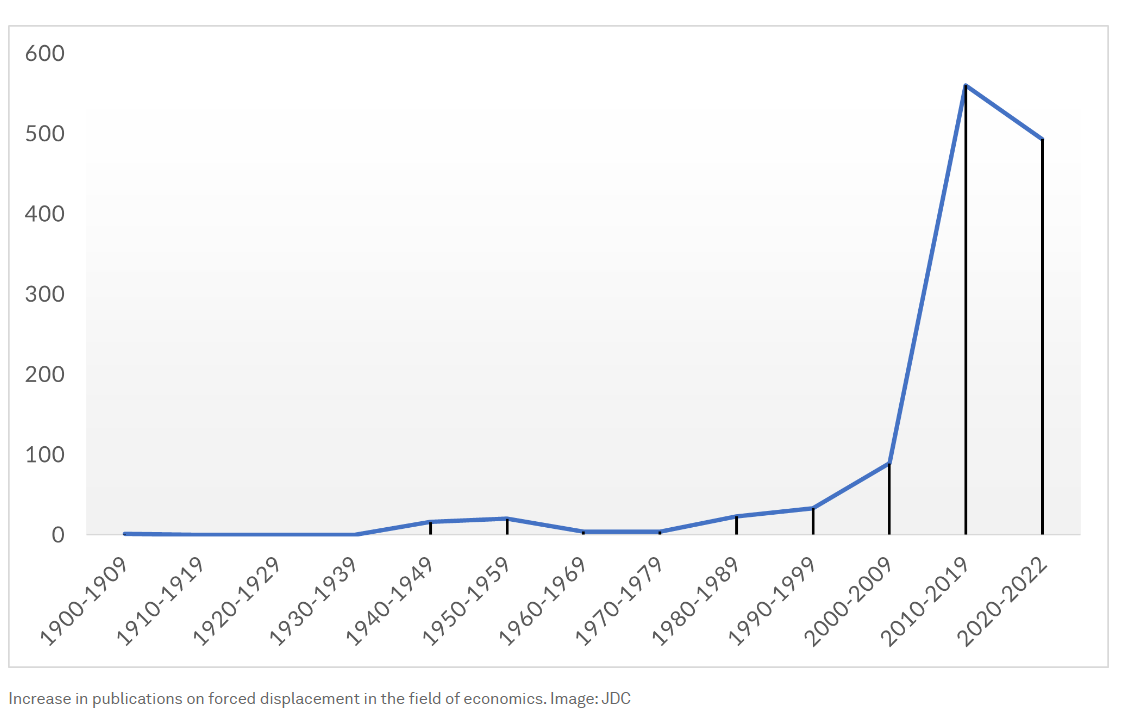

This abundance of data has spurred an exponential increase in the amount of research on forced displacement. In the last two years, almost 500 papers on forced displacement have been published in the field of economics, a stark contrast to the period from 1940 to 2009, when only 189 papers were published. Much of this research supports the narrative that refugees are more of an economic benefit than they are a burden. And, increasingly, we see evidence that policy-makers are making use of the data and the evidence that has been generated.

As data and evidence on forced displacement has proliferated, the JDC has tried to ensure that the quality of this information is, at best, preserved and, if possible, improved. This has been concretized in our support for the Expert Group on Refugee, IDP (internally displaced persons) and Statelessness Statistics (EGRISS).

Comprising members from 56 national statistics authorities from regions and countries affected by forced displacement and statelessness, and 36 regional and international organizations, EGRISS develops recommendations on standards for international statistics. Endorsed by the UN Statistical Commission, these standards help ensure that statistics on forcibly displaced and stateless people are comparable across time, different populations and areas.

All this work reveals that, when it comes to data and evidence on forced displacement, gaps still persist. So, last May, the JDC gathered a group of experts to determine exactly where the blanks are and how to fill them.

The group concluded that data on internally displaced people has glaring gaps and, in countries affected by fragility, conflict and violence, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Niger, Sudan, Syria and Yemen, there is also a lot more data needed. This was something that we anticipated when, six months earlier, we gathered a number of expert data scientists to discuss how innovative data tools can be applied to these contexts.

*Former Head, World Bank-UNHCR Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement

**first published in: Weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer