by Sinan Ulgen*

The European Green Deal attempts to decarbonize the EU’s economy and turn Europe into the world’s first climate-neutral continent by 2050. Because the deal is presented as a long-term growth strategy for the union, it consists of many different transformative policies, initiatives, and dimensions that aim to decarbonize various sectors. Since its first communication on the European Green Deal in December 2019, the European Commission has recognized the need for greater international ambition in the form of targets and political commitments to combat climate change and substantially reduce emissions worldwide.

The commission acknowledges carbon leakage as a potential negative effect of the EU’s own decarbonization efforts if international levels of ambition to reduce emissions remain low. The commission defines carbon leakage as the relocation of production to countries with fewer emissions constraints due to increasing costs of EU-based production because of climate policies. As a result, while reducing emissions in a specific region, relocating production may in fact increase total emissions worldwide. To address this challenge, the December 2019 communication states that “the Commission will propose a carbon border adjustment mechanism, for selected sectors, to reduce the risk of carbon leakage.” Since then, the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) has gradually taken shape and become a clear and distinct mechanism to prevent carbon leakage and support the EU to achieve its climate goals.

Designed as a border tax, CBAM will inevitably have significant impacts on many countries. There is a need to understand the vulnerabilities of the EU’s trade partners, particularly developing countries and least developed countries (LDCs), to this measure. CBAM’s potential to generate negative externalities for these countries also raises questions about climate justice. A political economy perspective can help explore how affected countries can implement adjustment policies to mitigate CBAM’s negative consequences on their exports, competitiveness, and, ultimately, welfare—and how the EU can improve the design of CBAM to contribute more to this needed adjustment.

The origins and functioning of CBAM

CBAM was introduced as part of a larger package of proposals known as Fit for 55, which aims to cut the EU’s emissions by 55 percent by 2030 compared with 1990 levels. The CBAM is motivated more by the need to disincentivize EU businesses from relocating than the need to decrease global emissions, though the it could help reduce EU emissions by up to 55 million tons compared to a baseline scenario by 2030. The commission initially selected five emissions-intensive trade-exposed (EITE) industries to be covered by the mechanism—cement, fertilizers, iron and steel, aluminum, and electricity—due to the high risk of carbon leakage in these sectors. In addition, CBAM has been extended to hydrogen and indirect emissions under certain conditions. This extension is especially important because including indirect emissions may significantly increase the pressure on countries with low institutional capacity to monitor and report product-based emissions. Going forward, the scope of CBAM is likely to be extended further to other carbon-emitting industries.

Similar to the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS), which places a limit on the right to emit certain pollutants but allows firms to trade emissions rights, CBAM will be based on certificates. Companies that import goods into the EU will be required to purchase certificates that represent the amount of emissions generated during the production of these goods. The commission will calculate the price of these certificates, which will mirror the ETS to comply with World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. Following the adoption of the relevant regulation by the European Parliament on April 18, 2023, CBAM’s transitional phase will start in October 2023. During this phase, importers will be obliged only to report their emissions; actual border taxation will begin in 2026.

Even though CBAM was initially presented as a mechanism to mitigate the negative spillover of the EU’s climate policies, such as the ETS, and as a strategy to protect EU industries by ensuring a level playing field, it does not only focus on domestic concerns. EU institutions frequently point out that CBAM is also a policy aimed at encouraging the EU’s international partners to take steps on climate action. This dimension of CBAM is particularly important because it implies that the mechanism will impose costs on other economies, thus creating an incentive for partner countries and private-sector actors to align closely with the EU’s climate goals and ambitions.

The impacts of CBAM and third countries’ vulnerabilities

Analyzing the international impact of CBAM, a policy that has not yet entered its transitional phase, is not an easy task because of uncertainties over the design and scope of the carbon tax regime. First, the scope of CBAM will most likely be extended to other EITE goods in a way that would drastically change its overall impact on the EU’s trade partners. The treatment of indirect emissions introduces another layer of uncertainty. But more importantly, an impact analysis should not rely solely on the effects of CBAM on trade flows and the costs imposed on companies. Instead, it should also consider the specific internal dynamics of third countries with regard to their long-term climate policies, the carbon intensity of the sectors covered by CBAM, and the mechanism’s impact on competitiveness.

The countries most affected by CBAM

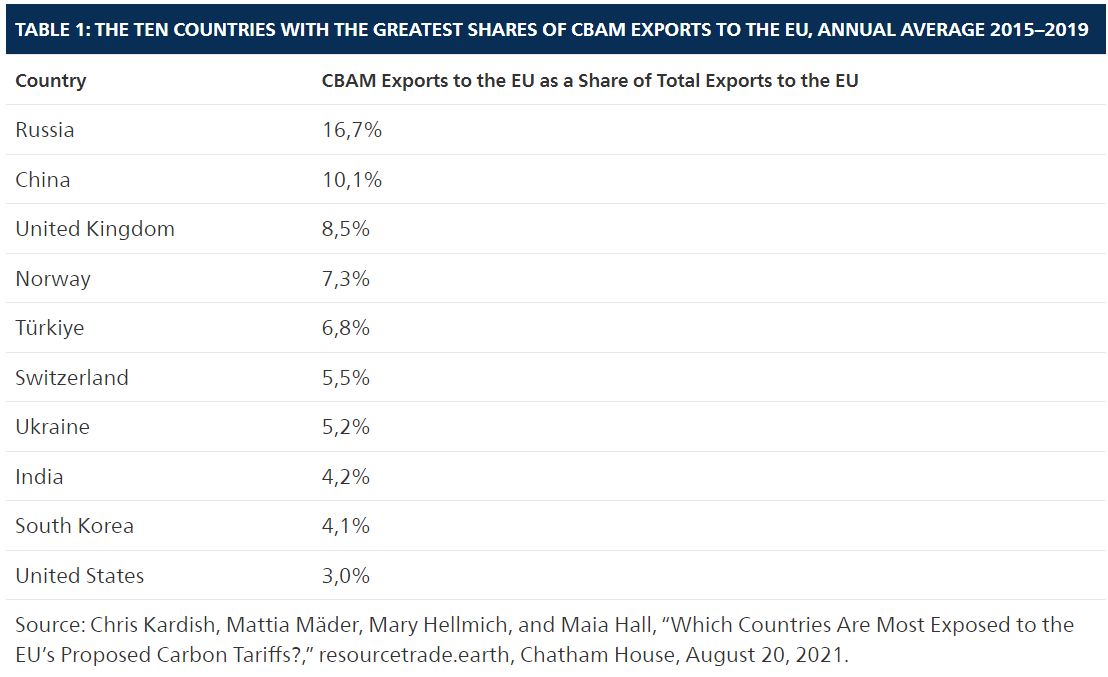

The annual average share of exports to the EU covered by CBAM between 2015 and 2019 for the ten leading countries ranged from nearly 17 percent for Russia to 3 percent for the United States. (However, Norway and Switzerland—both in the top ten countries—are part of the ETS, so CBAM will not apply to them.) Almost half of exports to the EU in the sectors covered by CBAM came from the top five countries. In short, the biggest exporters to the EU of CBAM products that will be affected by the mechanism are Russia, China, the United Kingdom, Turkiye, Ukraine, India, South Korea, and the United States.

Yet, even though these countries are the top exporters of CBAM goods to the EU, this does not mean that these states will be those most affected by the mechanism. For instance, although China is the second-biggest exporter of these goods, the overall size of the Chinese economy and its relatively low dependence on exports to the EU dramatically reduce China’s vulnerability to the mechanism. Therefore, examining the impact of CBAM on third countries requires an analysis of these exporters’ dependence on their exports to the EU.

In reality, the overall impact of CBAM will depend on the size of exports covered by the mechanism as a share of total exports to the EU. A 2022 study by the French Development Agency showed that even if countries such as Russia, China, Turkiye, and Ukraine could be considered those most affected by CBAM by virtue of their trade volume with the EU, the mechanism’s relative impact will be higher for other countries. The research highlighted that of the top seven countries by volume of CBAM exports, only Ukraine is among the top five in terms of the share represented by these exports and, hence, the relative impact of the mechanism. Moreover, the research showed that many of the EU’s smaller trade partners are at risk because of their high dependence on exports of CBAM products to the EU.

Mozambique is by far the most affected economy in relative terms, as almost 20 percent of its total exports are products covered by CBAM—or rather, to a major degree, a single good: aluminum. According to this measure, most of the countries most affected by CBAM—such as Mozambique, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Ukraine, Serbia, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Zimbabwe, Moldova, and Albania—are either low-income countries (LICs) in Africa or LDCs or developing countries in the EU’s neighborhood. Additionally, it should be noted that Russia and Turkiye, ranked first and third by total CBAM exports, drop to fourteenth and thirteenth place, respectively, in terms of the share of CBAM goods in these countries’ total exports to the EU.

While it is useful to analyze both the absolute volume of CBAM exports and their relative importance, it is also necessary to adopt a more holistic approach and examine the mechanism’s socioeconomic impact. In one of the first examples of this approach, researcher Clara Brandi studied this issue from a developmental perspective. Her analysis indicated that even though the share of a country’s exports to the EU may be low, as in a low-income economy such as Ghana’s, these sectors could be important sources of employment. Therefore, even if trade flows are small, applying CBAM in LICs can lead to a greater increase in unemployment and more negative socioeconomic consequences than in higher-income countries.

In a similar vein, the 2022 French Development Agency study examined the countries where the socioeconomic impact of falling production caused by CBAM is most likely to lead to unemployment and reduced wages. The study found that these countries are Moldova, Mozambique, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, North Macedonia, Ukraine, Montenegro, Bahrain, and Albania. According to the research, 2 percent of employment is exposed to the impacts of CBAM in Moldova and Mozambique. The research also concluded that Armenia, Georgia, Turkiye, and Zimbabwe have significant levels of exposure when it comes to wages—although “in these economies (with special regards to Zimbabwe), the share of employment at risk is not as high as the share of wages, indicating that few but [well-paid] jobs are those that may be impacted by the introduction of CBAM.”

The carbon intensity of the EU’s trade partners

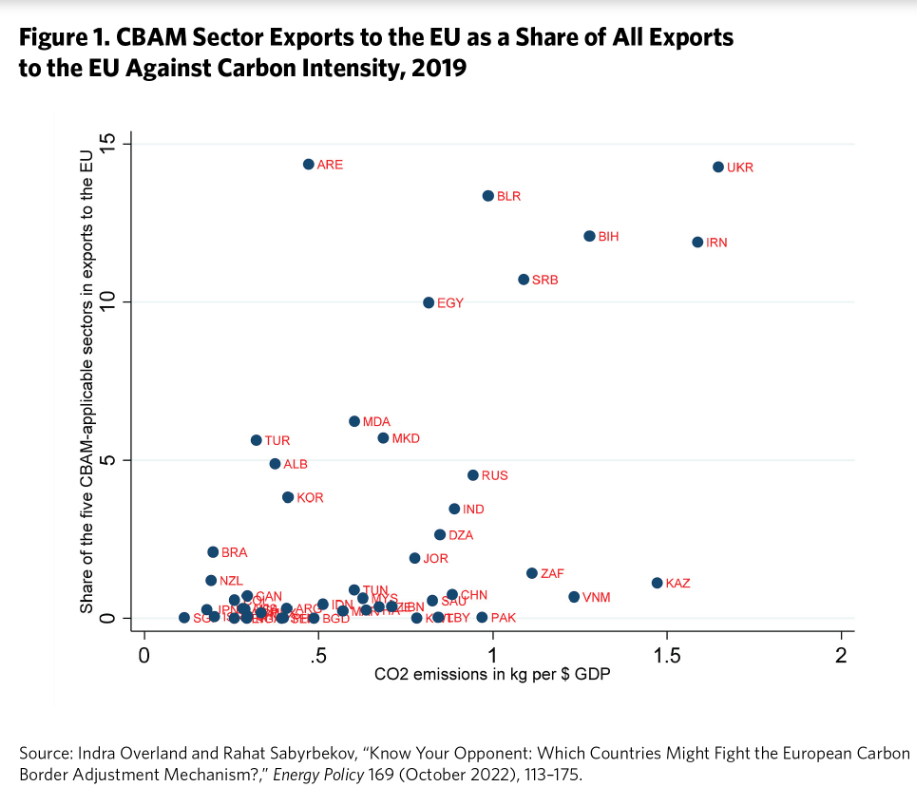

Another important indicator to assess a country’s vulnerability is the carbon intensity of its economy. Under CBAM, the carbon tax will be a function of the carbon embedded in the imported goods. If two countries export the same volume of CBAM goods to the EU, the difference between the carbon intensity of their industries could be a decisive factor that affects the tax burden and, ultimately, the competitiveness of those industries. A 2022 study by researchers Indra Overland and Rahat Sabyrbekov plotted countries’ CBAM sector exports to the EU as a share of their total exports to the EU against their carbon intensity (see figure 1). Of the EU’s trade partners, those with the most carbon-intensive economies in 2019 were Ukraine, Iran, Kazakhstan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Vietnam. Meanwhile, Ukraine, Serbia, and Bahrain had a high carbon intensity and were also among the countries that were more dependent on their exports to the EU.

Therefore, even if a country is exposed to CBAM because of its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions during the production process, the carbon intensity of the exports relative to those of other exporting nations is a critical factor. A country’s products may be subject to a tax burden based on their carbon content, but exports can remain competitive provided that they enjoy a lower carbon intensity than goods imported from other EU trade partners.

A 2020 Boston Consulting Group analysis that focused on the steel industry showed variation among the carbon footprints of steel producers in different countries. The study demonstrated that countries that predominantly use blast and basic oxygen furnaces to produce steel, such as China and Ukraine, are at a significant competitive disadvantage vis-a-vis countries that mainly use electric arc furnaces, such as India, Turkiye, and the United States. While the average carbon emissions in Turkiye and the United States are 1 metric ton (1.1 U.S. tons) of CO2 per metric ton of steel, Chinese and Ukrainian industries emit 2 metric tons of CO2 per metric ton of steel.

Pricing the carbon content of products imported by the EU increases developed countries’ share of exports of CBAM products while decreasing developing countries’ share. A 2021 research paper by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) showed that with a carbon border adjustment measure based on $88 per metric ton of carbon content, developed countries’ exports to the EU would increase in all sectors covered by CBAM except electricity, while developing countries’ exports, particularly those from Russia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Ukraine, Central Asia, Egypt, and South Africa, would experience a significant decline.

The same report showed that in the absence of such an adjustment, the opposite would be the case: developed countries’ exports to the EU would decrease proportionally, except in the aluminum sector, while developing countries’ exports to the EU would increase proportionally in every sector covered by CBAM. The report also emphasized that in this scenario, intra-EU trade of CBAM products would increase, which would have a similar effect to the imposition of a protectionist tariff by a regional trade bloc.

In fact, the UNCTAD scenario may downplay the potential impact of CBAM. With ETS carbon prices already at the level assumed by the study, the price level at the time of CBAM’s introduction will in all likelihood be higher, so the effects described by the UNCTAD analysis have the potential to be much more severe. For instance, according to unpublished research commissioned by the African Climate Foundation, at current carbon prices, CBAM could have the effect of reducing Africa’s exports to the EU by up to 5.7 percent. That would knock about 0.91 percent off the continent’s gross domestic product (GDP), equivalent to a $16 billion reduction in GDP at 2021 levels.

Statistical, monitoring, and reporting capacities

The institutional and administrative capacities of the EU’s trade partners and their current climate policies are other key factors that will affect the competitiveness of goods produced and exported to the EU. In a 2021 study, researchers at the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS) considered statistical capacity as one of the central factors in calculating the relative vulnerability of countries that will be affected by CBAM. Even if the volume of emissions generated in the export production process is small, reporting and monitoring responsibilities may create a significant cost for private and state-owned firms in certain countries and may hurt the competitiveness of their exports.

Because the capacity of firms in countries affected by CBAM to measure and report carbon emissions will be highly dependent on each country’s infrastructure and statistical capacity, the number of people trained in data processing and reporting procedures and the national data ecosystem will have significant impacts on the pricing of exports. Countries that already have high statistical and monitoring capacities do not have a major problem in this regard, while countries with low capacities will have a major vulnerability—so much so that even if the emissions of their exports are low, they may have difficulty in proving this status, and their products will be priced higher by CBAM.

A lack of adequate national infrastructure, a poor data ecosystem, weak statistical capacity, and a low number of people trained in data processing and reporting are common challenges in LDCs. As such, this dimension of CBAM will disproportionately affect the Global South.

Vulnerability trends

To have a more complete assessment of CBAM’s impact, it is imperative to explore future vulnerability trends beyond the mechanism’s impending effects on third countries. This is particularly important because CBAM is due to expand and, ultimately, cover a wider range of products. The European Commission and the European Parliament have indicated that the conditions under which CBAM will cover indirect emissions are to be determined in the near future. The EU defines direct emissions are those released “during the production process of the goods,” while indirect emissions are those “generated from electricity used for manufacturing, heating or cooling during the production process.” In the long term, many more countries will probably become exposed to CBAM, and nations’ relative vulnerabilities may change. In short, extending the scope of CBAM to indirect emissions in the future could disproportionately affect LDCs and developing countries.

The 2021 study by IASS researchers pointed to three main drivers and dynamics that can increase developing countries’ vulnerability to CBAM. First, in part due to population growth and income increases, these countries have a consistent increase in energy demand, which needs to be met by investments in energy and carbon-intensive energy systems. Second, these nations lack the financial and technical resources to create sustainable and clean energy systems in the long term. Third, the decarbonization of energy-intensive industries is costly and complex, requiring consistent policies implemented over a long period and complemented by additional support, such as subsidies and investments.

These main dynamics, which result in high carbon lock-in, also reflect what researchers Andreas Goldthau and Benjamin Sovacool call the four specific structural attributes of energy systems: vertical complexity, horizontal complexity, higher entailed costs, and stronger path dependency. Therefore, when the scope of CBAM is expanded to cover other sectors and indirect emissions, countries that do not have low-carbon energy systems and do not invest in the energy transition—mainly those in the Global South—will be particularly affected.

Many of these countries are also caught by a climate investment trap, which occurs when climate-related investments remain chronically insufficient due to a set of self-reinforcing mechanisms, with dynamics similar to those of the poverty trap. Energy system transitions generally require high investment. But the underdeveloped financial markets and domestic risks that are inherent in the economies of many developing nations lead to high-risk premiums and raise the cost of capital. This makes the transition more expensive and delays the reduction of carbon emissions. In addition, accessing climate funds is near impossible, particularly for fragile states, because international funding systems are so complex.

The complexity of energy systems, their intertwining with socioeconomic systems, and the difficulties of transforming these systems because of path dependency require international mechanisms, especially for countries in the Global South, to help these states mitigate the negative effects of CBAM in the long term.

In summary, four main findings encapsulate the projected effects of CBAM on third countries. First, the mechanism’s impacts are not distributed equally among nations: developed countries are not affected as much as developing ones, and in some cases, developed nations even benefit from CBAM thanks to the low carbon content of the products covered by the mechanism that they export to the EU. Second, in almost every category, the most vulnerable countries are either developing nations in the EU’s neighborhood or LDCs and LICs, mainly in Africa. Third, certain countries, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Mozambique, Serbia, Ukraine, and Zimbabwe, are among the most vulnerable countries in almost every category. Finally, in the long term, as the scope of CBAM expands, the vulnerability of LDCs and LICs will potentially increase because of structural challenges that these countries face.

CBAM ‘s compatibility with international principles

Examining the negative impacts of CBAM on third countries reveals that the mechanism has many shortcomings when viewed through the lens of climate justice and other internationally accepted principles. Regardless of the uneven distribution of the policy’s effects across countries, it is easy to observe that CBAM contradicts the EU’s own stated principle of “Do no harm.” Moreover, by negatively impacting the exports of developing countries and LDCs and creating additional socioeconomic challenges, the mechanism arguably goes against the principle of the right to development.

It is also difficult to square CBAM with the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and, more broadly, the principle of climate justice. The countries that are most vulnerable to CBAM have, historically, contributed less to global warming and benefited less from the industrialization associated with emissions than have the EU member states. Thus, developing countries and LDCs are significantly less able than European states to bear the costs of climate change.

Mitigation strategies for developing countries

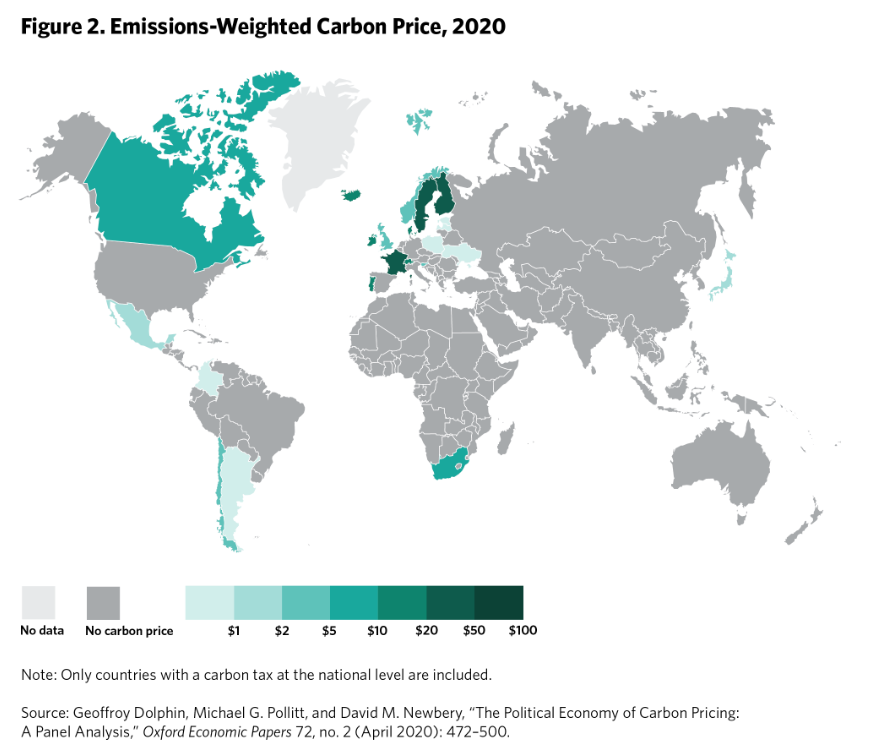

One option for the EU’s trade partners to reduce their exposure to CBAM is to adopt a carbon pricing scheme of their own. Depending on the scope and ambition of the scheme, a country’s exports can be totally exempted from the EU carbon tax at the border. An emissions-weighted carbon price is calculated by multiplying each sector’s carbon price by its contribution to the country’s CO2 emissions (see figure 2). At present, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and South Africa are the only developing countries that have launched a carbon tax scheme. But even for these countries, their carbon initiatives are not likely to mitigate the negative consequences of CBAM, given the carbon price differentials. For instance, in South Africa the price is set at around $7 per ton of CO2-equivalent emissions, almost an order of magnitude below the EU level. As a result, despite a domestic scheme of carbon pricing, South African exporters are due to receive little relief from CBAM.

The fundamental reason for this discrepancy stems from considerations to do with political economy. Governments in developing nations need to weigh up the popular support for such schemes. Getting domestic support for internal carbon taxation measures may prove more difficult in developing than in developed countries because voters in the developing world bear a larger marginal cost as a fraction of their total income. That is the main reason why poorer people are less inclined than richer people to pay more to avoid risk, including risks associated with climate change.

In addition, carbon taxation has been found to be regressive in higher-income countries because of the more carbon-intensive consumption patterns of poorer households, although the findings for less affluent economies are less conclusive. Under these circumstances, voters’ support for carbon pricing is determined by comparing the costs of a short-term increase in energy prices with the ongoing benefits of facing less climate change risk. Similarly, if people have smaller carbon footprints in their consumption and their jobs are not threatened by carbon pricing, they are more likely to support low-carbon policies.

The reality is that the carbon footprints of many households in developing nations are increasing—and will continue to increase as emerging middle classes seek to purchase energy-intensive durable assets, such as vehicles, air conditioners, and computers. Many households in developing countries lack the range of material durable goods that are part of a typical home in the West. Poorer households will therefore seek to obtain the same class of durable assets that allowed households in the Global North to improve their standard of living decades ago. However, this rising demand for durables is set to increase the greenhouse gas emissions of these nations over the short and medium term, at least until their electricity grids and transportation sectors can become less carbon intensive.

This consumption growth causes a political economy challenge because of the carbon-intensive lock-in effect that stiffens resistance to pricing emissions. Therefore, the middle classes in developing countries will support low-carbon policies only if they are compatible with their growing demand for consumer durables. Voters are unlikely to support government initiatives such as carbon taxation that can hinder their access to the range of goods that are associated with the prospect of enhanced living standards.

The way forward: exemptions and reallocations

CBAM’s international developmental impacts spark a debate on the ways to mitigate the mechanism’s negative spillover effects. In the near term, the EU should focus on increasing the range of CBAM exemptions and redistributing the revenue generated by the mechanism to the union’s trade partners. More broadly, the EU needs to examine CBAM’s global impact from a geopolitical perspective as well.

Given the perceived and unaddressed developmental impacts of CBAM, the EU’s first policy priority should be to expand the scope of countries exempted from the mechanism beyond those with ambitious carbon mitigation objectives. This category of exemptions should be made compatible with the multilateral trading regime and WTO rules, in particular the organization’s principle of most favored nation (MFN), which forbids discriminatory practices.

Viewed from that perspective, exempting low-income countries, such as LDCs, could be construed as a violation of the MFN clause but, in the words of researchers Andrei Marcu, Michael Mehling, and Aaron Cosbey, “would align with established international practice under the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities . . . in the climate regime and the Special and Differential Treatment . . . provisions of the WTO regime.” An exemption based solely on developmental criteria could also fall under the WTO’s enabling clause, which allows preferential treatment for developing countries. These exemptions would certainly improve LDCs’ welfare, yet they may result in higher carbon leakage and therefore run counter to CBAM’s objectives.

Second, the EU should create an accompanying instrument that redistributes the revenue generated by CBAM to the EU’s trade partners. This is necessary to address the negative economic impact that the mechanism will have on the welfare of the rest of the world. One 2018 study argued that carbon tariffs theoretically shift the economic burden of the developed world’s climate policies onto the developing world. A 2022 paper by researchers Sigit Perdana and Marc Vielle demonstrated that without accompanying support measures, the application of CBAM could lead to a welfare loss of 0.9 percent for LDCs, rising to 1.6 percent for African nations.

The proposed CBAM regulation estimated that the mechanism could generate €1.5–3.1 billion ($1.6–3.4 billion) in potential additional revenue, depending on the price of the EU allowance. The reallocation of this funding is also necessary to address the shortcomings of global green finance. At present, the geographic distribution of low-carbon finance is highly unequal. Developed regions are by far the largest recipients, while developing economies, particularly those in Africa, receive only a small proportion. This disparity in access to green finance determines the winners and losers from the adjustment to CBAM, as countries with more access to funding schemes are likely to accelerate their transitions. That will have detrimental consequences for the large set of developing and less developed nations, which will face negative competitive impacts in EU markets.

The design of a revenue reallocation policy will need to answer a few critical questions, starting with the criteria for the reallocation and the way in which it is targeted. On the former point, the options are, first, a scheme that reallocates CBAM revenue in proportion to the tax burdens of the exporting countries and, second, a more progressive scheme in which rebates are implemented on the basis of other socioeconomic criteria, such as income level or population size.

On the question of targeting, there are two broad options: the reallocation can consist of either targeted (conditional) or nontargeted (unconditional) transfers. A system of conditional transfers may include a domestic policy objective for beneficiary countries. For instance, government spending based on reallocated CBAM revenues can be used to finance clean investment in production, subsidize renewable energies, or promote efficiency measures in residential energy consumption. Identifying the most effective design of this reallocation policy is beyond the scope of this article, but according to the study by Perdana and Vielle, the use of this redistributed funding to subsidize energy-efficient household appliances provides for the largest welfare gains in LDCs and contributes most to carbon mitigation goals.

A geopolitical perspective

Beyond these economic considerations, the EU should also assess CBAM’s global impact from a geopolitical angle, especially in the wake of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Western nations have been surprised by the overall lack of enthusiasm among developing countries to strongly back their anti-Russia stance. Few non-Western leaders have condemned Russian President Vladimir Putin publicly or imposed sanctions on Moscow.

This lack of solidarity has deep roots. For instance, in Africa, many saw the European response to the war as a “prime example of double standards, given the disproportion in political and military support for Ukraine compared to assistance for African states battling aggression and instability, the generous welcome for those fleeing the conflict in eastern Europe and the scale of financial resources mobilised for Kyiv,” in the words of Paul Taylor and Youssef Travaly, senior fellows at the think tank Friends of Europe. But more broadly, as emphasized by Comfort Ero, president and chief executive of the International Crisis Group, “the war [in Ukraine] has revealed frustration in much of the world at the way Western power has been exercised over the past few decades.”

The global impact of CBAM should therefore be read in this specific context, where “Europe is always perceived to give with the one hand and take with the other, often more than it gives,” according to Elizabeth Sidiropoulos of the South African Institute of International Affairs.1 Implementing CBAM without due consideration of the points raised in this analysis while keeping the rules of global climate finance unchanged would only help reinforce this cleavage. Reforming CBAM by focusing more on its global and developmental impacts should therefore be a priority not only from the standpoint of climate justice but also as a result of broader geopolitical considerations that have been brought to the fore by the war in Ukraine. These realities should compel the EU to review the terms and scope of its engagement with the developing world.

*senior fellow at Carnegie Europe in Brussels, where his research focuses on Turkish foreign policy, nuclear policy, cyberpolicy, and transatlantic relations

**first published in: Carnegieeurope.eu

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer