by Ian Shine*

1. Interest rate rises slow down – but more still to come

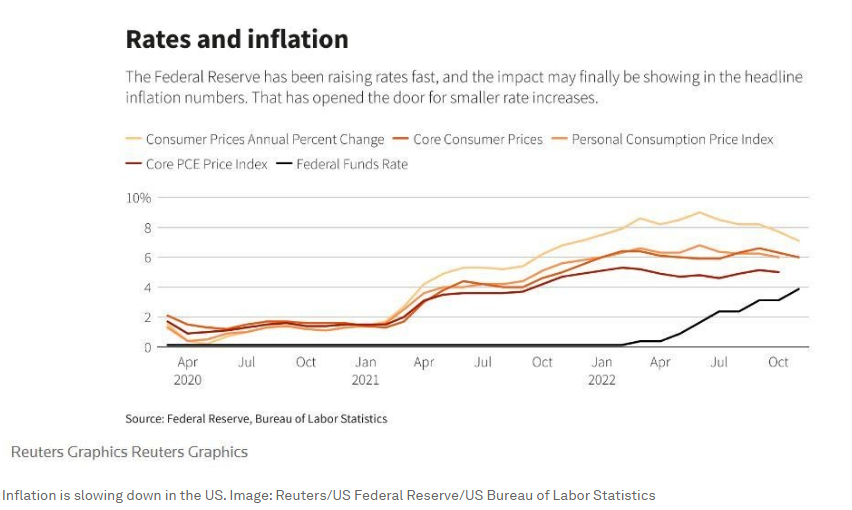

The US Federal Reserve (Fed), European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of England all slowed the pace of their interest rate rises this week, but indicated that the hiking cycle is far from over.

The Fed raised interest rates by half a percentage point on 14 December, following four consecutive rises of 0.75 points. But the central bank’s policy-makers expect to raise rates further – and keep them high for longer – than they had earlier anticipated. The Fed’s latest quarterly summary of economic projections projects the policy rate – now at 4.25-4.5% – reaching 5.1% by the end of next year, according to the median estimate of all 19 of the bank’s policy-makers.

The Fed has said it plans to tighten policy until it is "sufficiently restrictive" to bring inflation down. It is getting "close” to this, Chairman Jerome Powell said after the latest rise, but added that it is not there yet.

The ECB raised interest rates for the fourth time in a row on 15 December, putting them up by 50 basis points, following rises of 75 points at its past two meetings. However, it also said it expects to raise rates further, “based on the substantial upward revision to the inflation outlook”.

The central bank for the Eurozone has raised the interest it pays on bank deposits from -0.5% to 2% in just four months, reversing a decade of ultra-easy policy because of the sudden rise in prices. “Interest rates will still have to rise significantly at a steady pace to reach levels that are sufficiently restrictive to ensure a timely return of inflation to the 2% medium-term target,” it says. Eurozone inflation was 10.0% in November, slightly lower than the 10.6% recorded in October.

The Bank of England raised its key interest rate to 3.5% from 3% on 15 December, its ninth rate rise in a row, as inflation hit a 41-year high in October. The 0.5% rise was down from a 0.75% increase in November, but further hikes are likely. "The labour market remains tight and there has been evidence of inflationary pressures in domestic prices and wages that could indicate greater persistence and thus justifies a further forceful monetary policy response," the bank said.

2. Food prices likely to remain high in 2023

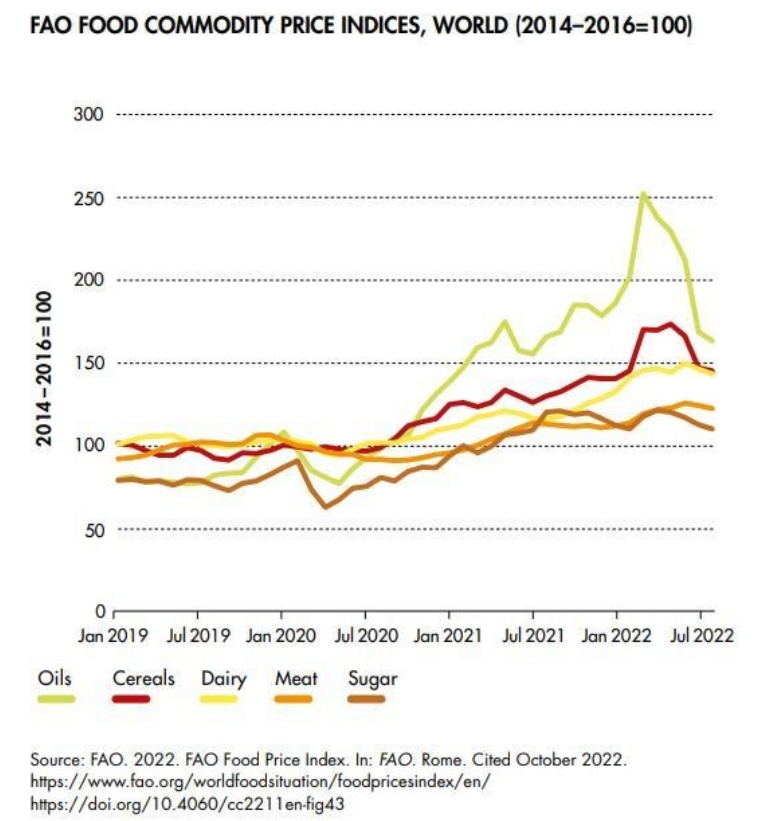

Global food prices are likely to remain elevated next year, as drought conditions or too much rain, the war in Ukraine and high energy costs look set to curb global farm production.

Production of staples such as rice and wheat is unlikely to replenish depleted inventories, at least in the first half of 2023, while crops producing edible oils are suffering from adverse weather in Latin America and Southeast Asia.

Food prices have hit record highs this year, impacting millions of people across the world, especially in poorer nations in Africa and Asia. Wheat, corn and palm oil futures have since dropped, but prices in the retail market remain elevated.

Recent flooding in Australia, the world’s second largest wheat exporter, has caused extensive damage to the crop, which was ready for harvest. And a severe drought is expected to shrink Argentina’s wheat crop by almost 40%. These events will reduce global wheat availability in the first half of 2023.

Rice prices are expected to remain high as long as export duties imposed this year by India, the world’s biggest supplier, remain in place.

The outlook for corn and soybeans in South America looks bright for its harvest in early 2023, although recent dryness in parts of Brazil, the world’s top bean exporter, has raised concerns.

US domestic supplies of key crops including corn, soybeans and wheat are expected to remain tight into 2023, according to the country’s Department of Agriculture. It forecasts US corn supplies falling to a decade low before the 2023 harvest, with soybean stocks at a seven-year low and wheat stocks at their worst level in 15 years.

Global food import costs across the world are on course to hit a record of nearly $2 trillion this year.

News in brief: Economy stories from around the world

Global debt remains well above pre-pandemic levels, standing at 247% of global GDP in 2021 compared with 195% in 2007, before the 2008-09 financial crisis and the pandemic, the International Monetary Fund says. This is despite the biggest drop in debt for 70 years in 2021, after debit reached record highs in 2020 because of the impacts of COVID-19.

China’s leaders are expected to reveal more economic stimulus measures when they gather this month to set the 2023 economic agenda. They are eager to underpin growth and to ease disruptions caused by a sudden end to COVID-19 curbs, policy insiders and analysts told Reuters.

US inflation appears to be slowing. Consumer prices posted their smallest annual increase in nearly a year in November, rising by less than expected for a second straight month. The consumer price index increased by 0.1% last month, after advancing by 0.4% in October.

However, US producer prices rose slightly more than expected in November amid a jump in the costs of services. But the trend is moderating, with annual inflation at the factory gate posting its smallest increase in one-and-a-half years.

Japanese wholesale prices rose by 9.3% from a year earlier in November, almost unchanged from the previous month. This appears to indicate the initial signs of inflation peaking amid easing global commodity prices.

German households are becoming less pessimistic about inflation prospects, predicting a moderation in price pressures over the next year, the Bundesbank says, based on a monthly survey of consumer expectations. The country’s wholesale prices rose by 14.9% on the year in November, slowing from an increase of 17.4% in October.

British inflation fell more than expected in November, after hitting a 41-year high in October. The annual rate of consumer price inflation dropped to 10.7% in November from 11.1% in October, the Office for National Statistics said.

The UK government is accelerating a consultation on the case for a central bank digital currency, reports Bloomberg. The Bank of England will release a paper setting out technology considerations informing the potential build of a digital pound. The move is part of a wider set of planned reforms of the UK’s financial services industry.

Investors are reportedly pulling record levels of bitcoin from crypto exchanges following the collapse of the FTX exchange. A total of 91,363 bitcoin were withdrawn in November, worth almost $1.5bn in total, The Financial Times reports.

Russia is on track to post a record high current account surplus this year, after its imports of goods and services fell due to Western sanctions, while globally high commodity prices boosted its export revenues. Its current account surplus more than doubled to $225.7 billion in January-November from $108.6 billion a year earlier, the central bank says.

Argentina’s inflation is expected to have cooled slightly in November, a Reuters poll of analysts showed, although prices are still set to rise by nearly 100% this year.

Russia’s central bank held its key interest rate at 7.5% at its final meeting of the year on 16 December but slightly shifted its rhetoric to acknowledge growing inflation risks, saying a recent military mobilisation was adding to labour shortages.

South Korea has flagged a deeper economic slowdown than expected at least through the first half of next year, and extended sales tax breaks on some fuel oil products and passenger cars by a few months.

More on economics from Agenda

Do cryptocurrencies have a future? They have been praised and condemned in equal measure by world leaders, and even become legal tender in some countries. But a risk expert speculates that they have now reached the beginning of the end.

Recent cross-country analysis by the OECD shows labour shortages have been on the rise in a number of advanced economies. A number of policy options can be considered to make jobs more attractive to workers, these experts say.

Accelerating digitalization has transformed the way we live and do business. But with the urgency of climate change now upon us, the next big change is coming into focus: a shift from a linear economy to a circular one. What can we expect this to mean in our everyday lives, for our infrastructures, and business models?

*Senior Writer, Formative Content

**first published in: Weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer