by Bindiya Vakil*

Some of the worst supply disruptions occur because manufacturers run short of low-cost items or raw materials that are widely used across a range of final products. We saw it during the pandemic with hospitals unable to secure masks and gloves. And we’re seeing it now: The inability to get a $5 semiconductor chip has brought the automotive industry to its knees. I recently read a story in the Washington Post that detailed how a shortage of cardboard boxes, each worth 26 cents, delayed a shipment of modules worth $33 apiece, while the lack of a 12 cent part, one of 20 components in another product, halted an assembly line for two weeks. What do all these items have in common? They all come from suppliers in the lower tiers of the supply chain.

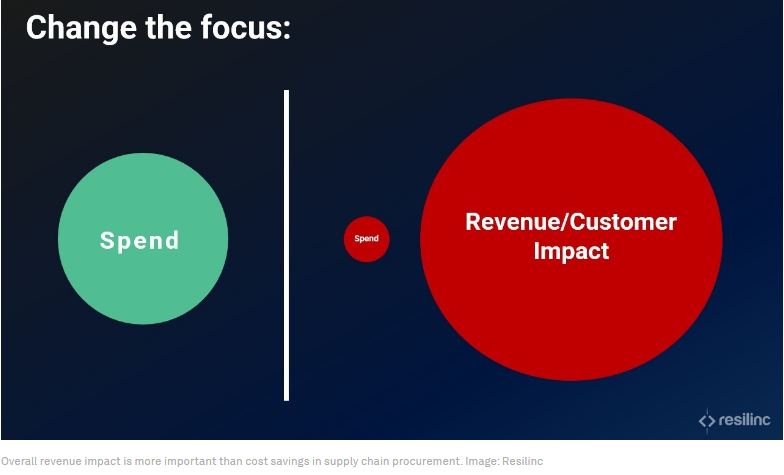

Procurement organizations have been told for decades that their number one priority is cost savings, followed by inventory reduction via strategies like Lean and Just-in-time (JIT). Often these objectives are tied to performance bonuses. With this mindset, procurement teams typically pay attention to the top 20% of suppliers that make up 80% of the spend, and work closely with those suppliers to track cost and negotiate savings. But this strategy is extremely risky because every part and raw material, irrespective of spend, is required to produce and ship the product. Think about it: If procurement teams only have visibility into 20% of their suppliers, that’s 80% of suppliers left to chance!

To build a more resilient supply chain, it’s vital to look at even the most inexpensive parts and materials when they are critical to products and revenues. This requires a change in mindset, from focusing the most attention on suppliers with the largest spend to focusing on those supplying products with the greatest potential to cut into your company’s topline.? Revenue impact needs to be the new way to segment and define critical suppliers.

This shift in mindset is easier said than done, especially because companies have spent years hiring procurement people who are comfortable with contentious supplier price negotiations. But this approach breaks down when continuity of supply is impacted and when there is not a collaborative manufacturer-supplier relationship grounded in transparency and trust. During disruptions, these procurement teams are often forced to pay high premiums to get parts in the door. One company I worked for paid $50 million in additional fees to secure inventory that typically cost $5 million.

Procurement needs to transform the very nature of the manufacturer-supplier relationship, rewarding supplier transparency with collaborative problem-solving, future business, and strategic status. This is because supply continuity to a manufacturer equates to revenue assurance for the supplier (a win-win). Both parties can identify areas of investment the supplier needs to make to ensure continuity of supply – and what the manufacturer will provide in exchange, such as more favourable pricing, preferential or trusted partner status, longer-term contracts, single sourced status, or other advantages.

Procurement can shape the competitive landscape for supply chains

Of course, collaborative problem-solving teams who build strategic supplier partnerships grounded in trust and transparency do not develop overnight. A strategic reset of this magnitude needs to be made from the top down. Apple CEO Tim Cook is a good example of this. Cook rose from procurement and used many of the strategies outlined in this article to leverage supply chain for competitive advantage.

As an example, in 2004 Apple bought most of the available touchscreen glass capacity to keep competition out of the tablet market for two years, cementing the iPad’s early market dominance. This visibility into its sub-tier suppliers and understanding how even the lowest-cost parts are crucial to the final product and revenue no doubt helped contribute to Apple becoming the most valuable company in history. This is also an excellent case study about how procurement leaders who think that strategically can rise to the top.

New metrics and KPIs

Leaders must develop their incentive programmes and methodologies. Instead of bonuses being based on meeting cost savings targets, incentives should focus on being rewarded for protecting continuity of supply and ultimately, profit. This means being measured on KPIs like the number of supply chain disruptions that caused manufacturing lines to go down; speed of detection; whether manufacturing lines went down; if suppliers were overpaid to secure constrained parts, or freight expedites were necessary.

More proactive supplier relationship metrics should measure teams for how much visibility and transparency the suppliers within their purview have; how well suppliers respond to assessment requests; the speed with which suppliers confirm impact about disruptions; and how quickly disruptions are resolved. These new metrics need to be added to the procurement organization’s operating models and operational review meetings, and targets need to be factored into their incentive compensation plans.

Mapping and monitoring as the foundation

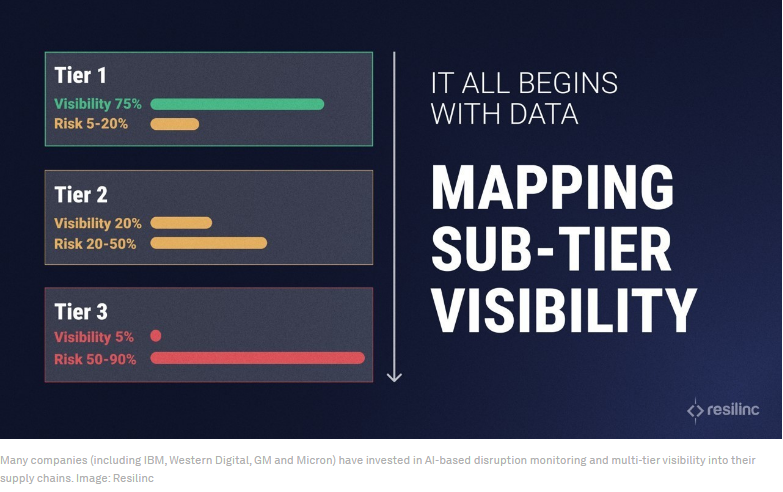

When it comes to protecting continuity of supply, procurement teams need to know where their parts are coming from and what they mean to the revenue. They also need to keep abreast of the latest developments that could impact the broader market and ultimately, their supply chains: factory fires, geopolitical events, commodity constraints, M&A, pandemic lockdowns are all examples. To solve these continuity challenges, many companies (including IBM, Western Digital, GM and Micron) have invested in AI-based disruption monitoring and multi-tier visibility into their supply chains.

One success story, stemming from the early days of the pandemic, involves a global electronics manufacturer. The company had recently expanded its mapping capabilities, from about 100 of its largest suppliers, prioritized by spend, to 650 suppliers ranked by strategic factors including whether a supplier was a sole source of a part, and the revenue impact of a delay or loss of that part at a specific site. With this capability, the supply chain team had precise knowledge of the sites where more than 7,500 parts and materials were produced.

When Wuhan began to shut down, the company was able to quickly identify the specific Wuhan-area sites where its parts and raw materials were sourced, enabling procurement staff to concentrate on communicating with the most critical suppliers, especially those that had reported impacts. Later, when California implemented its shelter-in-place order, the company identified within minutes one site that was storing a significant quantity of parts and supplies. With the duration of California’s lockdown unknown, the supply chain team worked with the supplier to ship 12 months’ worth of supplies from the California site to a site in another state with less stringent restrictions.

*Chief Executive Officer and Founder, Resilinc

**first published in: Weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer