by Helen Nugent*

“We are living in hell.” That’s how one person described the recent record-breaking heat wave in Pakistan.

Earlier this year, Australia recorded its hottest day with a temperature of 50.7C on its western coast, while Delhi in India registered its highest-ever temperature of 49C in May. Meanwhile, recent days and weeks have seen mercury-busting readings across Europe and North Africa, and large swathes of the central United States continue to endure scorching weather.

The deadly impact of heat waves

Heat waves can be deadly, with the elderly particularly at risk of heat exhaustion and heatstroke. According to the World Health Organization, between 1998 and 2017, more than 166,000 people died as a result of heat waves. In the UK alone, stifling temperatures claimed in excess of 2,500 lives in summer 2020.

Experts predict that climate change will increase the frequency and intensity of extreme hot weather. Climate scientists expect heat waves to be the ‘new normal’, with the World Weather Attribution saying recently that climate change made this year’s prolonged, devastating early heat in India and Pakistan 30 times more likely.

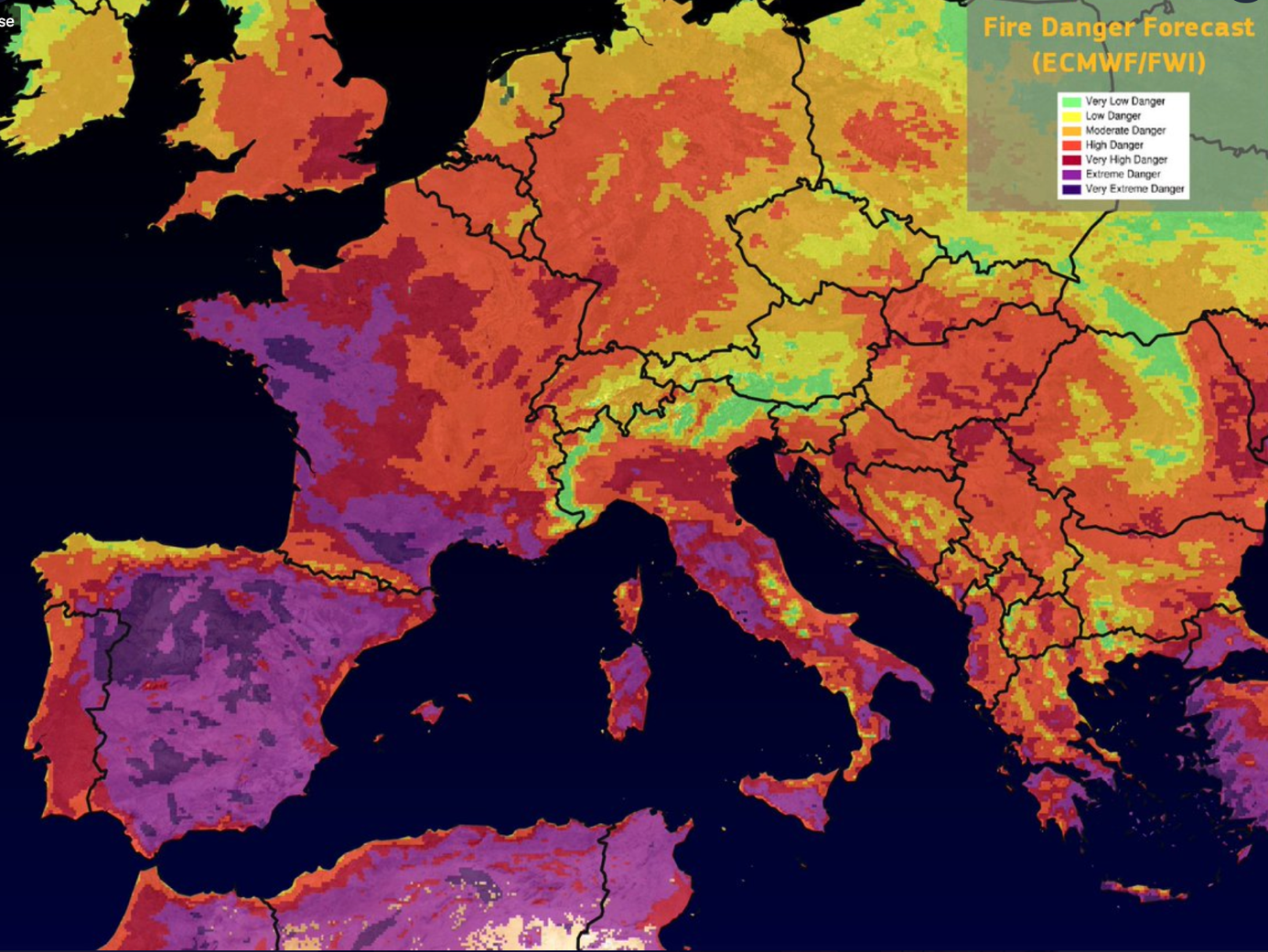

Aside from creating dangerous health conditions, heat waves increase the likelihood of droughts and fuel wildfires, which affect both animals and humans, points out NBC News.

Heat waves can impact economies as well as people and wildlife

And beyond the immediate threat to life, extreme temperatures can impact economies, too.

“Extended bouts of great heat can result in more hospital visits, a sharp loss of productivity in construction and agriculture, reduced agricultural yields, and even direct damage to infrastructure,” points out Phys.org.

Employees are less productive during hot weather, even if they work inside, while children struggle to learn in extreme heat, resulting in lower lifetime earnings which in turn hurts future economic growth, according to The Conversation. Indeed, a 2018 study found that the economies of US states tend to grow at a slower pace during hot summers. “The data shows that annual growth falls 0.15 to 0.25 percentage points for every 1 degree Fahrenheit that a state’s average summer temperature was above normal.”

And it’s not like air conditioning is a simple solution. For some, the technology is either not practical (outside workers) or is financially unattainable. And for those where air conditioning is an option, there are consequences down the line. One study anticipates that by 2100, greater use of air conditioning could increase residential energy consumption by 83% globally. And as The Conversation points out, “if that energy comes from fossil fuels, it could end up amplifying the heat waves that caused the higher demand in the first place”.

The financial cost of heat waves

A closer examination of the effect of very hot weather on economies reveals some extremely worrying statistics. For example, the European Environment Agency (EEA) estimates that, between 1980 and 2000, heat waves in 32 European countries cost up to $71 billion - and that’s before the deadly heat waves of the past two decades are taken into account.

Meanwhile, the International Labour Organization (ILO) predicts that, by 2030, heat waves could reduce the number of hours worked globally by more than 2%. That’s the equivalent of 80 million full-time jobs and a cost of $2.4 trillion - nearly 10 times the 1995 figure, says Phys.org.

What happens next?

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the negative effects of climate change are mounting much faster than scientists predicted less than a decade ago. The warnings are dire, not least the panel’s finding that a rise in global temperatures of more than 1.5C above pre-industrial levels may result in permanent and potentially catastrophic changes to our world.

Fast-tracking the switch to clean energy sources is vital, say scientists.

In the meantime, experts say that it is possible to prepare for heat waves, both physically and economically. Amar Rahman of Zurich Insurance Group believes that the key is “adaptation”. Among his recommendations are some for businesses that, he says, “need to adapt their buildings, infrastructure and working hours to higher temperatures”.

There are also benefits to so-called ‘urban greening’, where more trees and other vegetation can help to cool down cities and towns.

At an individual level, keeping the air flowing in rooms and buildings is important, as is staying hydrated.

*Senior Writer, Formative Content

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer