by Lord Nicholas Sternk, Hans Peter Lankes and Roberta Pierfederici*

There is a growing understanding that the deepening crises facing the world come from trends in our societies and economies that are becoming unsustainable. We must tackle the basic structural problems at their source.

The challenge is to recover and rebuild in a way that creates sustained growth and transforms our economies while tackling the social and ecological stresses caused by our current economic models. It is also clear that there is now a new and feasible approach to development across the world, which is much more attractive than the dirty and destructive paths of the past. But the world must invest and act quickly to get there.

The wars and hardening geopolitical divisions we are witnessing underscore the precious opportunity to act together, globally, on an agenda in which all countries have an overwhelming interest.

Net-zero and nature-centred transformation, investment-driven growth and innovation, an inclusive approach to tap human talent while managing insecurity, and a process of international collaboration that fosters common goals – this will be the growth story of the 21st century. The private sector will take centre stage, with global investment being 80-90% private. And much of the private sector has, with rapidly increasing scale, committed to sustainability, responsibility, and net-zero emissions.

We described the path forward in a briefing paper to help frame the debate at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos in May 2022. Here, we focus on the centrality of investment, innovation, policy, and finance in driving a new growth model.

1) Investment in the right kinds of capital and infrastructure

The future of people and the planet will be shaped by the capital investments realized over the next 10-20 years, capital that can drive clean, green, job-rich and much healthier growth than what came before. To drive the low-carbon transformation, global investment must increase by around 2–3% of GDP per year above pre-pandemic levels. This investment will be primarily in the private sector, but public investment must complement and catalyse this.

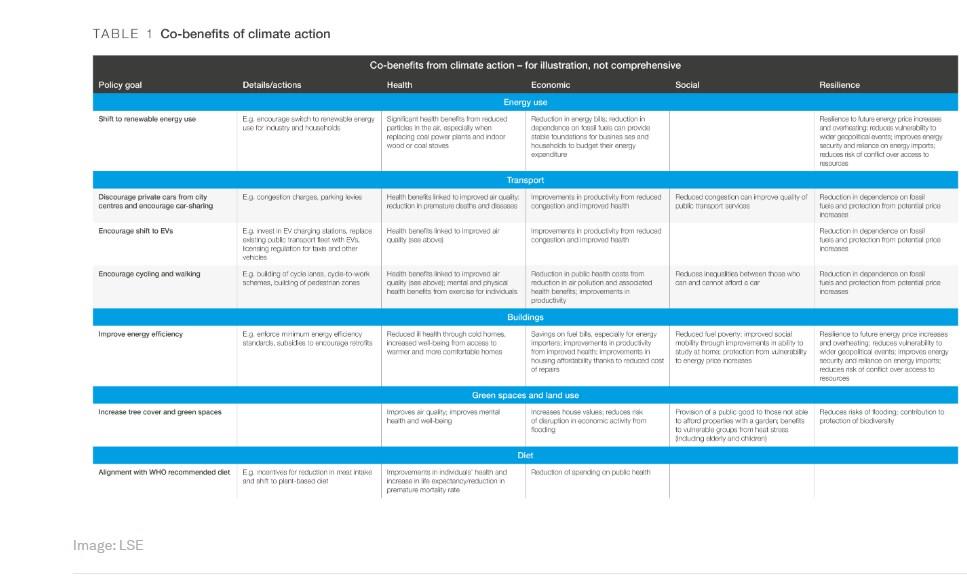

Why do we believe that this is possible? Because investment ratios are far below potential, the energy transformation opens up vast new markets, technology is yielding increasingly high returns, and the world continues to produce excess savings that can feed investments. Investments should not be misperceived as costs. They can propel more efficient, cleaner, and inclusive growth and create further private sector opportunities, along with many other significant co-benefits (see Table 1).

2) Innovation and systems transformation

Much of the fundamental structural change needed lies in transforming the key systems of energy, transport, industry, cities and land. All require combinations of institutional change, standards and regulation, design and good policy. Fortunately, revolutions in digital and AI enable the management of these systems in new ways.

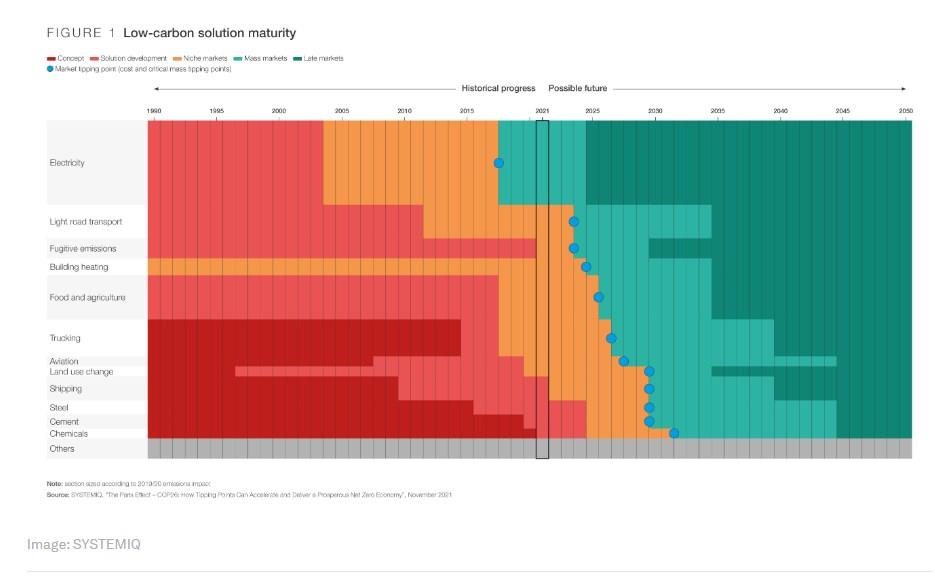

The potential is immense: By 2030, low-carbon solutions could be competitive in sectors accounting for nearly three-quarters of emissions, compared to one-quarter today (mainly in electricity) and no sectors only five years ago (see Figure 1). Public-sector support and partnership will be crucial for technologies that face high upfront costs and uncertain returns; initiatives such as Mission Innovation, the International Solar Alliance, the Climate Action Platform and the Glasgow Breakthrough Agenda are powerful examples.

3) Policies to foster investments, innovation and a just transition

A big push on investments and innovation requires credible and supportive policy and governance that can create confidence in future returns. Implementing a price on carbon is central for efficiently shifting production and consumption towards lower-carbon sources. Beyond pricing, rapid changes in the use of coal and petrol will require regulatory action to avoid unacceptably steep price hikes. The design of our towns and cities must be re-shaped towards cycling, pedestrian and public, and shared transport.

Appropriate actions should also be taken to support a just transition, to ensure that the benefits and opportunities of the shift to a new economy are shared widely while helping those affected by economic losses or dislocation.

4) Finance and international cooperation

International cooperation around policies, technology and finance will be crucial to realise the required big push on investment and innovation if action is to be on time and at scale.

Country platforms can provide a focal point and help overcome the main obstacles to greater investments in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), which often include policy and institutional hurdles, a lack of project development capacity, and the absence of reliable channels for large-scale finance.

While many advanced economies have fiscal space or borrowing ability, EMDEs entered the latest crises with high debt and limited resources. Domestic resource mobilization, largely taxes, will have to contribute to incremental finance. But international financial collaboration will be critical.

Donors from developed countries fell short of delivering on the $100 billion goal by 2020, but there is an opportunity to step up and deliver in 2022. Furthermore, as the financing challenge exceeds fiscal capacity by far, the private sector must be enabled to contribute most of the finance.

We identified six key sources of finance that need to scale up, each making specific and important contributions:

Private sector: quantitatively the biggest source of finance, but strongly dependent on the implementation of good policies, country platforms and risk management; the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), launched at COP26, creates major potential in this direction.

Bilateral official finance: Concessional finance from bilateral donors is central to international climate priorities, including a just transition, adaptation, and investments in natural capital. Donors should double bilateral climate finance from its 2018 level to $60 billion by 2025.

Multilateral Development Banks: MDBs can play a key role in supporting the development of country platforms and policies to improve the flow and cost of capital by reducing, managing and sharing risk. MDBs will need to triple their climate-related lending from 2018 levels by 2025. The shareholders should insist on the expansion but also stand behind them in support of risk-taking, including growing their capital base.

Multilateral agencies: While the sums are smaller than for MDBs, institutions such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the Adaptation Fund can be valuable in mobilizing others.

Philanthropy: Philanthropic organizations are well equipped to provide finance for activities that lack market support, such as adaptation and resilience, and they do not create new indebtedness.

Voluntary carbon markets: By helping deliver finance to projects that demonstrate innovative ways of reducing emissions footprints, VCMs can also drive early investment in green technologies that would otherwise lack access to finance; again, these do not create new indebtedness.

These six financing sources are complementary. Combining them within policies and platforms to foster investment could launch the world on a new course of development.

*Chair, The Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change&the Environment and Visiting Professor in Practice, The London School of Economics and Policy Analyst and Research Advisor to Professor Stern, London School of Economics and Political Science

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer