by Stefanie M. Falconi*

Agriculture has come a long way in the twenty-first century. From precision irrigation systems to face recognition in livestock to deploying drones for improved crop yield, emerging technologies are reinventing farm country. Whether it’s hyperspectral monitoring (scanning soils and plant health) or tracking cattle’s movement and health, computing advances are making new technologies – powered by data – readily accessible for agriculture. The revolution in agriculture is delivering savings along with improved productivity. It is also big business: precision agriculture is expected to grow to a $11.1 billion industry in the next five years.

Smart regulations make a difference in conservation

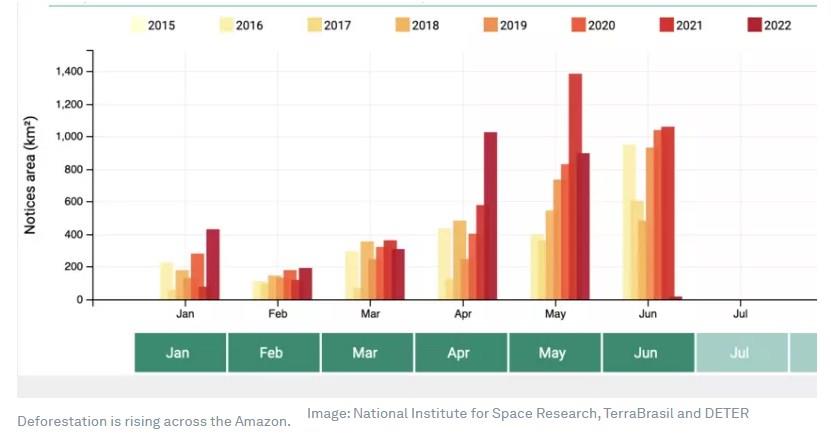

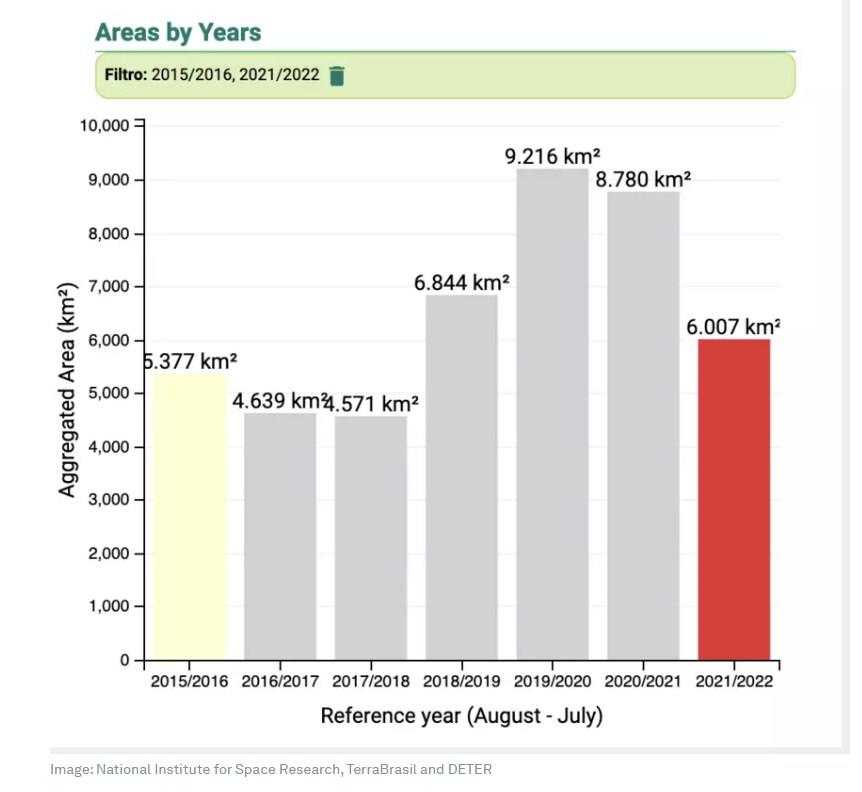

Brazil is a major benefactor of high-tech agricultural wonders. Despite the abundance, vast tracts of its forests – especially in the Amazon Basin – still fall to slash-and-burn farming, medieval ranching, and resource pirates. The reason is complicated. Fixing the problem doesn’t have to be. As deforestation continues to rise, a Science Panel at the Summit of the Americas called for a more ambitious commitment to conserving the Amazon Basin as it approaches a dangerous tipping point. Encouragingly, past incentives programs show how smart regulations and targeted incentives make a significant difference in conservation.

Deforestation in Brazil is driven by demand and impunity. Brazil kept pace with global demand for soy, timber, and meat, and hyper-specialized industries like high-end leather for luxury SUVs. The country’s efforts to meet international appetites comes at an environmental cost, especially when forest products are not properly accounted for and monitored. And where secrecy lurks, so can crime. Agriculture and livestock in the Amazon basin are too often linked to illicit deforestation, illegal logging, and public land grabbing. But even here, the storyline is hardly straightforward because the industries themselves walk a tenuous line between the legal and the illegal.

Natural resource laundering needs to be stopped

Take the case of the cattle industry, recently the subject of several investigative reports. Journalists documented how illegally sourced Amazon basin resources are converted into legal products entering global markets, a process dubbed “cattle laundering”. The practice entails shuffling cattle between grazing lands to disguise their origin. Determining origin is crucial because it’s the only way to connect products tied to illegal activities such as land clearing, illegal logging, planting monoculture or even grazing pastures. Of course, natural resource laundering has occurred for decades across the extractive industries. What makes the cattle business different is how easily technology can trace product’s origins.

The good news is that there is incredible innovation in the tracking of commercial goods: Think of internet shopping and real-time precision in package delivery. Yet, it’s puzzling how little many consumers know – or care – about the source of items they purchase. Technology is necessary, but an insufficient, solution. Often the missing middle comes down to incentives.

Rewriting incentives to promote sustainable practices

The primary obstacle to tracking goods was hardly the lack of technology. The scarcity of incentives is far more problematic. So long as financial institutions continue to bankroll extractive industries with questionable track records on environmental activities, the cycle of environmental crime will persist.

There are two crucial steps to curbing land degradation and deforestation: clear traceability of products and financial incentives for forest conservation. Policymakers could start by rewriting incentives to promote sustainable practices. China’s success in the late 1990s with the Grain for Grain program gives early clues on how to do this. In Brazil, the record is less encouraging.

The financial sector can play a crucial role by offering new lines of financing mechanisms, anchored in environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles. Though it would be a stretch to expect ESG to reinvent markets, much less to persuade wholesalers and outside bidders bent on chasing prices and market share to mend their ways. Real change entails cooperation between different economic players. Investors can promote smart practices, while public authorities bolster tech-enabled regulations and enforcement to safeguard against setbacks. Though a small portion of the global market, some investors care about risks in their supply chains and the long-term effects beyond quarterly earnings. Nevertheless, for all the goodwill and global compacts, the path to sensible development takes hard work and it must include the public, private, and consumer sector.

Without regulatory frameworks, impact is limited

Smart technology has limited impact without smarter regulatory frameworks and enforceable laws. Despite earnest promises to green up the supply chains, there are few incentives to track raw materials; why bother when these are seen as replaceable. As markets begin to account for environmental degradation and the climate-related risks that pose real threats to financial investments, this could change. Bankers, boards and shareholders are taking note of climate change-related financial risk. Ultimately, when consumer pressure grows, incentives will follow making tracking, inspecting and vetting central to putting everyday products on our tables and in our homes.

*WEF Fellow to Global Future Council, Senior Researcher at Igarape Institute

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer