by Douglas Broom*

The war in Ukraine has plunged Europe into an ethical dilemma over energy. Russia is the continent’s leading supplier of imported oil, gas and coal, and politicians across the EU are looking for ways to end that dependence.

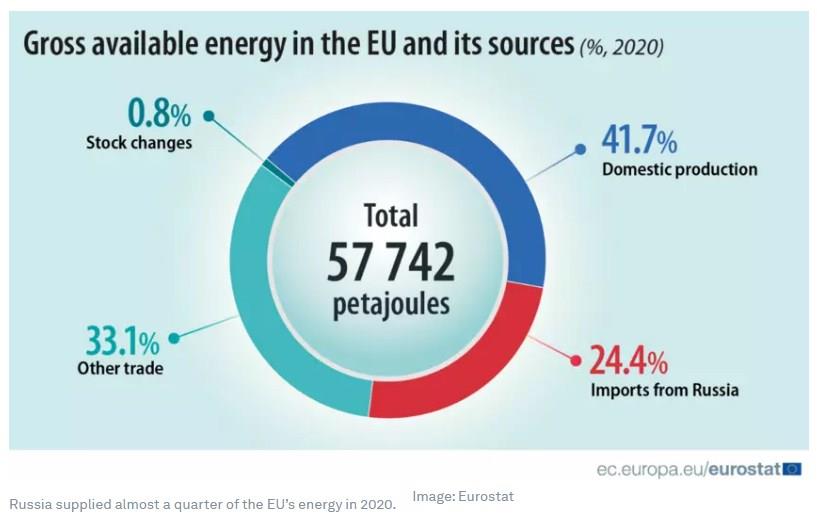

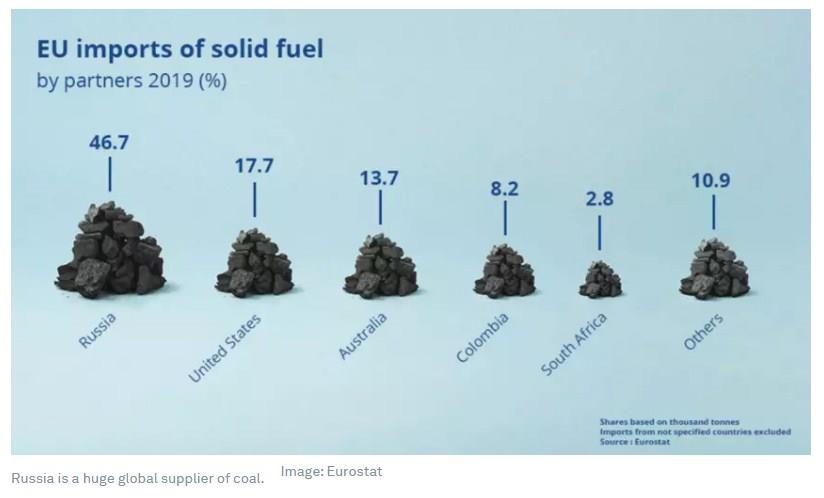

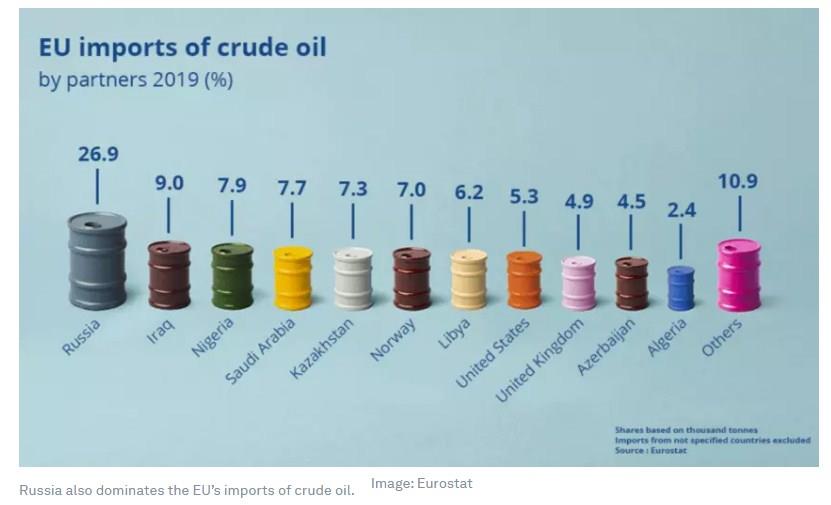

Russia accounts for about two-fifths of the EU’s gas imports, 26.9% of its imported crude oil and almost half of its supplies of solid fuel – meaning solid matter, such as coal, that can be used to produce energy. In all, imports from Russia accounted for a quarter of Europe’s energy consumption in 2020, second only to the 42% produced from the EU’s own resources.

Russia is also the world’s largest exporter of natural gas, the second-largest supplier of crude oil after Saudi Arabia, and the third-largest coal exporter behind Indonesia and Australia.

In 2021, three-quarters of Russia’s gas exports and 49% of its crude oil exports went to Europe, including to non-EU members such as Norway and the UK, the US Energy Information Agency says. The biggest customer for Russian coal exports was China.

And EU countries paid $107 billion for Russian energy imports last year, almost two-thirds of the total value of goods it imported from Russia.

Getting away from Russian energy

But things are set to change. On 8 March, the European Union announced a plan to end all Russian energy imports by 2030. This could cause energy costs to soar, but the EU said it will protect businesses and consumers in the bloc by using price regulation, state aid and taxation.

“We must become independent from Russian oil, coal and gas. We simply cannot rely on a supplier who explicitly threatens us,” said European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen.

There’s been no shortage of advice to the EU on how to break its energy dependence on Russia. The International Energy Agency (IEA) has produced a 10-point plan outlining how Europe could wean itself off Russian gas. This involves a mixture of maximizing gas storage, sourcing gas from other sources and increasing the amount of power generated from renewable and low-emission sources.

Filling the continent’s gas storage to 90% of capacity is a feature of the EU’s own plan, which also calls for a boost to energy efficiency and a rapid increase in the use of renewables.

“Let’s dash into renewable energy at lightning speed,” said Frans Timmermans, who heads the EU Green Deal. “Renewables are a cheap, clean, and potentially endless source of energy and instead of funding the fossil fuel industry elsewhere, they create jobs here.”

Launched in 2019, the Green Deal aims to more than halve EU greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and take Europe to net-zero by 2050. “It is time we tackle our vulnerabilities and rapidly become more independent in our energy choices,” added Timmermans.

In reality, Europe had begun a shift away from fossil fuels even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As a result, it is ahead of many other regions in its preparations for the transition to a low-carbon future.

Nine of the top ten nations in the World Economic Forum’s Energy Transition Index 2021 were European countries. Russia was ranked 73rd.

*Senior Writer, Formative Content

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer