Negotiating a salary increase or a job promotion ranks high on the list of hard conversations to have at work, and it doesn’t get any easier without a plan.

“People think, ‘I’m just going to knock on their door, sit down with them and noodle around and see where this goes.’ That’s not a plan. You want to have a specific goal in mind,” said Maurice Schweitzer, Wharton professor of operations, information and decisions. “People often fail to achieve their conversational goals because they fail to identify their objectives.”

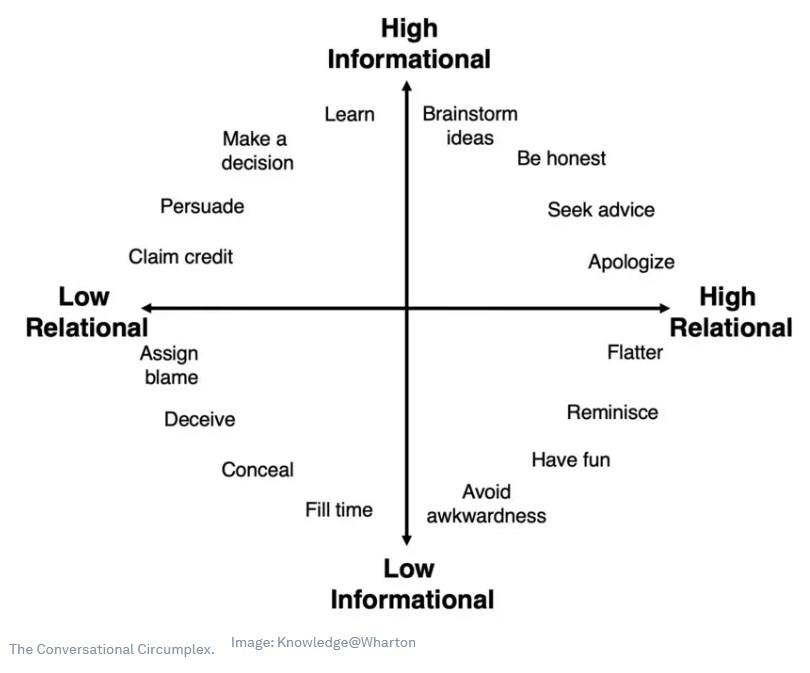

In his latest paper, Schweitzer and his co-authors introduce a framework to help people have more successful conversations by identifying and understanding the motives of each participant. The model is called the “conversational circumplex,” and it maps conversations along two key axes: informational and relational. (See image below.)

A conversational partner with high informational goals seeks to share or gather information to support a decision or action, such as sharing the latest sales numbers to devise a strategy to gain market share. A conversational partner with high relational goals seeks to develop or deepen a relationship. For example, this person may want to create a favorable impression, conceal a secret, or have fun spending time together.

“If we are more precise in our objectives for the conversation, it will help us prepare and plan, guide us more clearly, and ultimately yield greater success,” Schweitzer said.

The paper is titled “The Conversational Circumplex: Identifying, Prioritizing, and Pursuing Informational and Relational Motives in Conversation,” and it appears in the April issue of Current Opinion in Psychology. Schweitzer’s co-authors are Michael Yeomans, assistant professor of strategy and organizational behavior at Imperial College Business School, and Alison Wood Brooks, associate professor of business administration at Harvard Business School.

Schweitzer said he and his co-authors were interested in exploring what it means to have a good conversation beyond the vague notion that it went well or poorly. In reading the literature on the topic, they realized there wasn’t a clear definition of what constituted a successful conversation, so they set out to create a roadmap. The result — the conversational circumplex — can be applied to just about any conversation in the workplace and beyond, whether chatting with a boss, co-worker, spouse, relative, child, or friend.

“Across different conversation partners, across different points in time, our goals are going to change,” Schweitzer said. “And the strategy for having a good conversation in one context can be very different for another.”

Schweitzer was particularly interested in conversational goals because he teaches a business class on negotiation, which is a type of conversation that is typically both informational and relational. An employee asking for a raise, for example, wants to develop a facts-based case for a raise but also nurture the relationship with the manager who will ultimately make the decision.

The Conversational Circumplex: This framework classifies conversational goals along two key dimensions: informational and relational. This panel shows where a conversationalist might plot some of their goals on the circumplex. The placement of motives on the circumplex is subjective, and the goals depicted here represent a subset of the vast array of motives that conversationalists might have.

“When I talk to my students about negotiating salaries, I tell them that the first thing to do is get on a train to New York or a plane to Chicago — it’s one thing to say that I care about the relationship and this [job], but something entirely different to show up,” he said. “Showing up means I care about the relationship and want you to know that I care and that it’s a priority for me.”

The manager taking part in the negotiation has a responsibility to gather information, understand the motives of the employee, and give appropriate feedback. If a raise isn’t possible because of budget constraints or equity concerns, are there other options or future opportunities for more money?

A company-wide meeting is another example of communication that is both informational and relational, Schweitzer said. At an all-hands meeting, the CEO wants to impart information but also build a sense of community, foster positive feelings, and motivate employees.

“When I’m a CEO talking to my employees, I am trying to communicate information but also a sense of identity, concern about our relationship, concern about our community,” he said. “I want to do things like recognize people who are mentoring others. We’re all in this together, we’re all making sacrifices, were all pitching in and together we can accomplish something transformational.”

Finding Common Conversational Ground

The researchers ran a large study to develop the conversational circumplex, collecting data to confirm that the points on the axes are properly placed and grounded in reality. When pursuing multiple conversational goals, such as seeking advice and brainstorming ideas, the closer the goals are on the circumplex, the more likely that both can be achieved. For example, claiming credit for an idea is completely different from apologizing, while being honest is adjacent to brainstorming ideas.

“When we have multiple goals, it’s easier when those goals are similar,” Schweitzer said. “It’s difficult to be honest and to conceal information because those are opposing objectives. But it is easier to seek advice and to be honest. Those are more similar, more consonant goals.”

The paper also identifies specific behaviors that come out of conflicting goals in a conversation, such as backhanded compliments (“You know a lot about cool bands for someone your age”), humble bragging (“My hand hurts from signing so many autographs”), and prosocial lying (“You look great”). It’s critical for conversationalists to recognize whether or not these behaviors advance their goals.

For important conversations — both in and out of the workplace — Schweitzer encourages people to use the circumplex to think about their objectives beforehand. After, they should think about the extent to which they achieved or failed at those objectives, and then consider what they could have done differently.

“I think we can all learn.” Schweitzer said. “Rather than being haphazard, having a clear objective will guide us to be more precise about what we do and when we do it.”

*first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer