by Kristalina Georgieva*

When the Group of Twenty finance ministers and central bank governors gather in Jakarta, in person and virtually, this week, they can take inspiration from the Indonesian phrase, gotong royong, “working together to achieve a common goal. This spirit is more important than ever as countries are facing a tough obstacle course this year.

The good news is that the global economic recovery continues, but its pace has moderated amid high uncertainty and rising risks. Three weeks ago, we cut our global forecast to a still-healthy 4.4 percent for 2022, partly because of a reassessment of growth prospects in the United States and China.

Since then, economic indicators have continued to point to weaker growth momentum, due to the Omicron variant and persistent supply chain disruptions. Inflation readings have been higher than expected in many economies; financial markets remain volatile; and geopolitical tensions have sharply increased.

That is why we need strong international cooperation and extraordinary agility. For most countries, this means continuing to support growth and employment while keeping inflation under control and maintaining financial stability—all in the context of high debt levels.

Our new report to the G20 shows just how complex this obstacle course is and what policymakers can do to get through it. Let me highlight three priorities:

First, we need broader efforts to fight ‘economic long-Covid’

We project cumulative global output losses from the pandemic of nearly $13.8 trillion through 2024. Omicron is the latest reminder that a durable and inclusive recovery is impossible while the pandemic continues.

But considerable uncertainty remains about the path of the virus post-Omicron, including the durability of protection offered by vaccines or prior infections, and the risk of new variants.

In this environment, our best defense is to move from a singular focus on vaccines to ensuring each country has equitable access to a comprehensive COVID-19 toolkit with vaccines, tests, and treatments. Keeping these tools updated as the virus evolves will require ongoing investments in medical research, disease surveillance, and health systems that reach the “last mile” into every community.

Upfront financing of $23.4 billion to close the ACT-Accelerator funding gap will be an important down payment on distributing this dynamic toolkit everywhere. Going forward, enhanced coordination between G20 finance and health ministries is essential to increasing resilience—both to potential new SARS-CoV-2 variants, and future pandemics that could pose systemic risks.

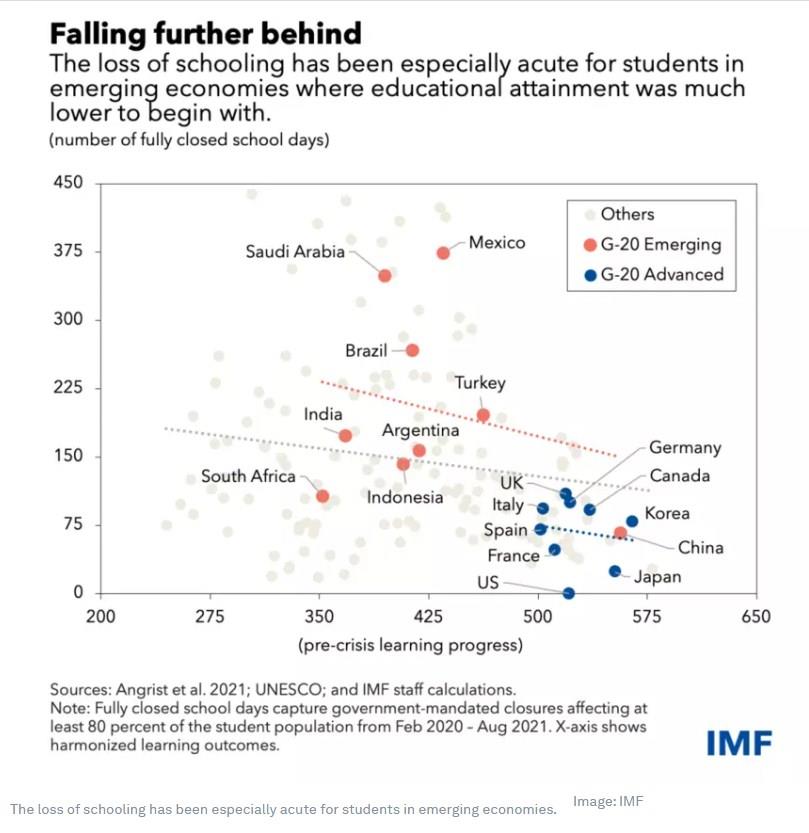

Ending the pandemic will also help address the scars from economic long-COVID. Think of the profound disruptions in many businesses and labor markets. And think of the cost to students worldwide, estimated at up to $17 trillion over their lives due to learning losses, lower productivity, and employment disruptions.

School closures have been especially acute for students in emerging economies where educational attainment was much lower to begin with—threatening to compound the dangerous divergence among countries.

What can be done? Strong policy action. Scaling up social spending, reskilling programs, remedial training for teachers and tutoring for students will help economies get back on track and build resilience to future health and economic challenges.

Second, countries need to navigate the monetary tightening cycle

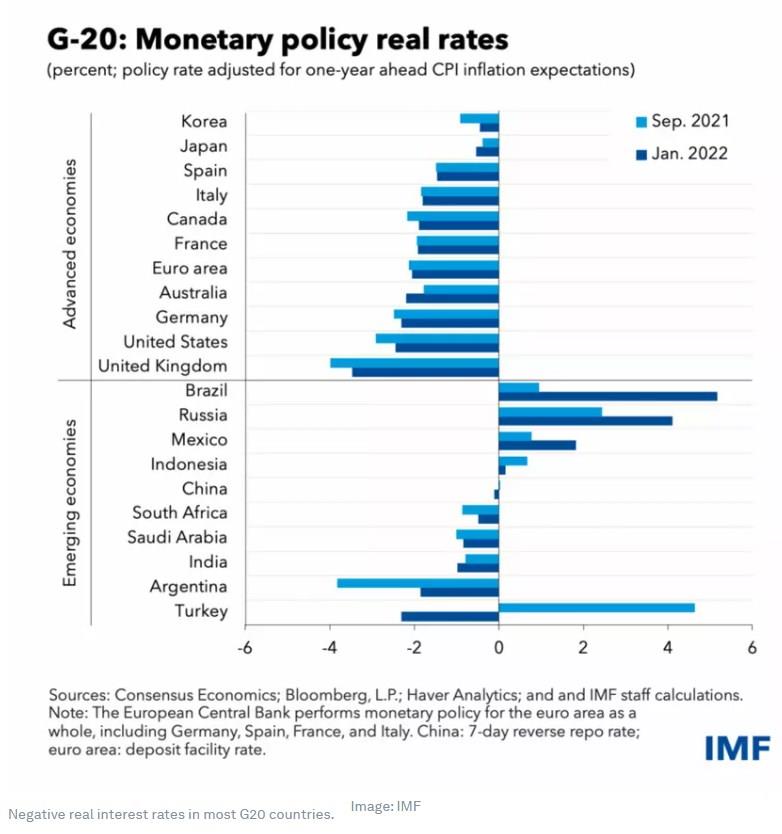

While there is significant differentiation across economies and high uncertainty going forward, inflation pressures have been building in many countries, calling for a withdrawal of monetary accommodation where necessary.

Going forward, it is important to calibrate policies to country circumstances. It means withdrawal of monetary accommodation in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, where labor markets are tight and inflation expectations are rising. Others, including the euro area, can afford to act more slowly, especially if the rise in inflation relates largely to energy prices. But they, too, should be ready to act if economic data warrants a faster policy pivot.

Of course, clear communication of any shift remains essential to safeguard financial stability at home and abroad. Some emerging and developing economies have already been forced to combat inflation by raising interest rates. And the policy pivot in advanced economies may require additional tightening across a wider range of nations. This would sharpen the already difficult trade-off countries face in taming inflation while supporting growth and employment.

So far, global financial conditions have remained relatively favorable, partly because of negative real interest rates in most G20 countries. But if these financial conditions tighten suddenly, emerging and developing countries must be ready for potential capital flow reversals.

To prepare for this, borrowers should extend debt maturities where feasible now , while containing a further buildup of foreign currency debts. When shocks do come, flexible exchange rates are important for absorbing them, in most cases, but they are not the only tool available.

In the event of high volatility, foreign exchange interventions may be appropriate, as Indonesia successfully did in 2020. Capital flow management measures may also be sensible in times of economic or financial crisis: think of Iceland in 2008 and Cyprus in 2013. And countries can take macroprudential measures to guard against risks in the non-bank financial sector or where property markets are surging. Of course, all these measures may still need to be combined with macroeconomic adjustments.

In other words, we need to ensure that all countries can move safely through the monetary tightening cycle.

Third, countries need to shift their focus to fiscal sustainability

As countries emerge from the grip of the pandemic, they need to carefully calibrate their fiscal policies. It’s easy to see why: extraordinary fiscal measures helped prevent another Great Depression, but they have also pushed up debt levels. In 2020, we observed the largest one-year debt surge since the second world war, with global debt—both public and private—rising to $226 trillion.

For many countries, this means ensuring continued support for health systems and the most vulnerable, while reducing deficits and debt levels to meet their specific needs. For example, a faster scaling back of fiscal support is warranted in countries where the recovery is further ahead. This in turn will facilitate their shift in monetary policy by reducing demand and thus helping to contain inflationary pressures.

Others, especially in the developing world, face far more difficult trade-offs. Their fiscal firepower has been scarce throughout the crisis, which has left them with weaker recoveries and deeper scars from economic long-Covid. And they have little scope to prepare for a post-pandemic economy that is greener and more digital.

For example, the IMF last year described how green supply policies, including a 10-year public investment program, could raise annual global output by about 2 percent compared to the baseline on average over 2021-30.

All these policy actions can help us find a new modus vivendi for a more shock-prone world. But they may be hampered by debt. We estimate that about 60 percent of low-income countries are in or at high risk of debt distress, double 2015 levels. These and many other economies will need more domestic revenue mobilization, more grants and concessional financing, and more help to deal with debt immediately.

That includes reinvigorating the G-20 Common Framework for debt treatment. This should start with offering a standstill on debt service payments during the negotiation under the framework. Quicker and more efficient processes are needed, with clarity on the steps to go through, so that everyone knows the road ahead—from formation of creditor committees to an agreement on debt resolution. And make the framework available to a wider range of highly indebted countries.

The IMF’s role

The IMF plays an important role in this area by providing macroeconomic frameworks and debt sustainability analyses. And we encourage greater debt transparency: by requesting greater disclosure of what a member country owes and to whom when it seeks IMF financing, and by working with our members through the IMF-World Bank Multi-Pronged Approach to debt vulnerability.

We also need to build on the historic allocation of Special Drawing Rights of $650 billion. As well as holding the new SDRs as reserves, some members have already begun to put them to good use. For example: Nepal for vaccine imports; North Macedonia for health spending and pandemic lifelines; and Senegal to boost vaccine production capacity.

To magnify the impact of the allocation, we encourage channeling of new SDRs through our Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, which provides concessional financing to low-income countries, and the new Resilience and Sustainability Trust.

With its cheaper rates and longer maturities, the RST could fund climate, pandemic preparedness, and digitalization policies that would improve macroeconomic stability for decades to come. The G20 has given its strong backing to the RST, and we aim to have it fully operational this year.

As countries face up to multiple challenges, the IMF will support them with calibrated policy advice, capacity development, and financial assistance where needed. The key is to bring agility into all aspects of policymaking—but even that is not enough.

We also need to follow the spirit of Indonesia’s motto, Bhinneka Tunggal Ika—”Unity in Diversity.” Together we can get through the obstacle course to a durable recovery that works for all.

*Managing Director, International Monetary Fund

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer