by Chengyi Lin*

Performance reviews are clearly in need of an overhaul. A 2019 Gallup poll found that a mere 14 percent of employees are strongly inspired to improve by their performance reviews. At best met with a lack of enthusiasm, at worst with resentment, this annual exercise in the era of The Great Resignation has scope for improvement.

Solutions are possible, for example, research shows that workers consider evaluations based on their own past performance to be fairer than those comparing them with the performance of colleagues. Yet self-reflection might need a bit of structure when it comes to evaluations.

Google conducts its bi-annual performance cycles in March and October. Post-Project Oxygen, it has become the model company to measure and value the performance of “good managers”. Working closely with the company, I saw the attention top executives put on talent in the middle and senior management team, and the encouraging focus on people development in the organisation.

As Stephanie Davis, Vice President of Google Southeast Asia, said: “Google is a technology company. But our successes come from our talent. It is our people who generate impacts for Google, our customers and our stakeholders in the local communities.”

While working with Google, I was also working with a leading global consulting company – also a “people” business. Its senior management team raised concerns about losing talent. The challenge of talent retention has topped the HR agenda for years, partly due to generational changes and the lure of tech giants and start-ups.

Instead of staff returning to the office, many companies see an increasing number of talents exiting in pursuit of other opportunities. From my recent interactions, an estimated 70 percent of senior executives view high churn and a shortage of talent supply as significant challenges for their companies in the short term.

There are multiple factors contributing to the high churn rate, such as hiring freezes during the pandemic, personal or family situation changes, job categories change, etc. However, the company’s performance review practice is often overlooked as a contributor to talent loss.

The performance review is a critical part of business continuity and talent management. In most companies, it centres on the “evaluation of individual performance”. Simply put, how individual performance meets pre-set targets – cascading KPIs, how an individual’s performance contributes to the team’s goals, and how the company performs as a collective.

In addition to this top-down approach, many companies include upward feedback as inputs for supervisor performance evaluation. Good practices, like at Google, go a step further and guide supervisors to have periodic conversations on career aspirations, opportunities and development areas. In practice, the time and attention allocated to these conversations, however, varies depending on the individual supervisors.

If we pause and reflect on performance review, it’s clear that despite all the efforts, the current practice feels lopsided – leaning heavily, if not solely relying, on performance, particularly business performance. How can we balance our performance review with consideration of the needs and well-being of talents?

Complementary criteria in performance reviews

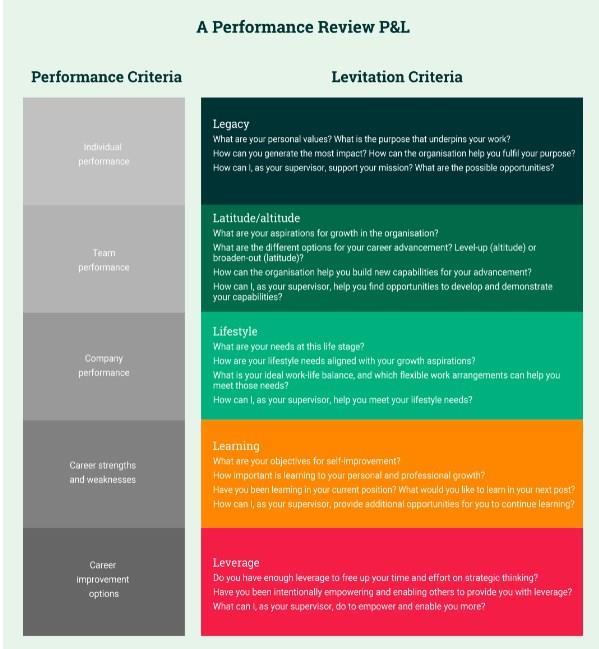

One example comes from a participant in one of my high-potential talent programmes. We suggested adding a set of complementary criteria to the existing performance review. The new questions draw attention to the alignment between external targets mandated by the position and the intrinsic drive of the individual.

Casey* has been a senior manager for four years. She has six direct reports but oversees a 34-member team. Internally, she has been viewed as an expert on the product, process and industry, as well as an excellent people manager. Her performance review was outstanding over the past three years, so she has been identified as a high potential leader.

However, she has been passed over for two internal promotion opportunities, which went to external female candidates. Casey candidly shared with me that she was too busy with both her work and family and was not aware of the first position. Although she put herself forward for the second one, the interviewing team did not feel she had the capabilities needed for the position. How could it be that a high potential with outstanding performance reviews was not promoted?

Casey and I sat down and started to look at a new list. Taking an analogy from accounting’s profit and loss statement, our L is for levitation and is a complement to the traditional criteria for the P of performance. The new P&L provides insights into Casey’s story.

Here are some of the questions I asked:

Legacy: What are the legacies you want to leave behind?

Casey loved this question. After years of “meeting the targets”, she forgot to consider why she is working so hard on them.

After some reflection, Casey realised that she did care about the promotion, not because she wants a bigger role or pay cheque. Instead, Casey believes that the new position will allow her to generate more impact on her customers and their community. The ability to influence external stakeholders is very important for her purpose.

Latitude/altitude: What options do you have?

For Casey, this question helped her realise that instead of a blinkered upward-only focus, she can also look around to find interesting and fulfilling opportunities around the same level to expand her horizon. For example, after chatting with a few connections suggested by her supervisor, Casey discovered new positions in other regions that could give her the external exposure, as well as an entrepreneurial experience, to grow both the business and build her own team.

Lifestyle: What are your needs at this life stage?

At 3 and 5, both of Casey’s kids are still relatively young. “It is the perfect stage to travel and expose them to other cultures.” She and her husband would like to live abroad for a few years before the children settle down for their schooling. “This has always been on my mind.” Casey opened up, “But I don’t know when it is a good time to share it with my manager. The performance review is too formal and a lot of pressure … a ‘FYI’ is too casual … and I also don’t want to come across as threatening to leave.”

Learning: Have you been growing?

Casey was always engaged in my class – asking good questions and sharing great insights. She is a very curious person. When we discussed this, Casey lowered her head. “I don’t think I’ve been learning a lot in the past year or so.” After being identified as a high potential, Casey felt more pressure to perform and maintain her reputation. This led to long hours, additional commitments and not a lot of time to learn. There is a broader agreement among participants in many of the high potential programmes; as a high potential, you are expected to deliver more, which stifles the time and effort to continue learning.

Leverage: Do you have enough leverage to focus on strategic issues?

As an excellent people manager, Casey spent a lot of time on her team. Developing her team members is a priority but at the same time, she holds the final decisions, as she is ultimately accountable for her business unit. This creates a huge challenge for Casey. When she looked at her calendar, Casey realised that she spends 92 percent of her time in meetings on operational issues, including emergencies. The remaining 8 percent of the time, she participates in strategic meetings. She simply does not have time and mind space to “think” about strategic issues such as stakeholder engagement, industry thought leadership or other long-term strategic directions. “I need to empower my team more to make decisions. I can then allow myself more time and energy to think about bigger issues for the longer term.”

Casey is only one example of the many high potentials who benefited from this additional list of levitation criteria. It does not only balance the traditional performance-focused evaluation criteria, but also counters the relentless gravity that pulls managers towards operational issues and emergencies. The new talent “P&L” can help companies understand the personal values and needs of their critical talent and identify alignment. It can also help the talent self-reflect and explore new options for career advancement.

*Affiliate Professor of Strategy at INSEAD

**first published in: knowledge.insead.edu

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer