by Ben Smith*

The global challenges of the climate crisis, alarming biodiversity loss and the COVID-19 pandemic are striking reminders of how vulnerable life on earth is.

People are part of nature and these challenges are largely of our own making. If we want the planet to remain habitable, a different balance must be struck between people and planet in the future.

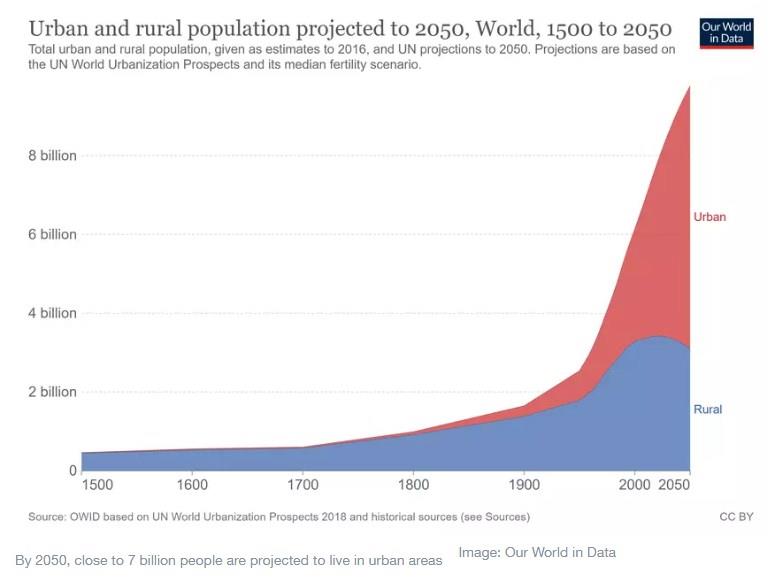

More than half the world’s population now lives in cities with that number expected to reach 68% by 2050. It is estimated that 60% of the additional land set to become urban in the next decade is yet to be built on, and some of the most rapidly expanding urban areas globally are in biodiverse tropical forests in Brazil, West Africa and Asia.

While rapid urbanization remains a threat to biodiversity, existing cities are emerging as critical spaces – with the right physical scale and human capital – in which to innovate and cooperate to bring forward solutions that will help build resilience to future shocks and stresses.

It is a traditionally held view that cities are generally devoid of any biodiversity, but that is not the case. Recent studies suggest that the world’s cities, including spaces in old parking lots, roof gardens, parks and created wetlands, offer important refuges for plants and animals – even for some more threatened and endangered species.

It is not only biodiversity that is important in cities, but the relationship between people and nature. The more that can be done to connect people to nature in cities, the more city dwellers will come to appreciate the natural environment and the benefits it provides, whether that is for its intrinsic value or its function – from flood attenuation to shade or as spaces for play and exploration. If we can foster this conservation spirit in cities it will likely have benefits everywhere.

A 2019 report by C40 Cities, Arup and University of Leeds found that urban consumption from just 94 of the world’s mega cities contributes to 10% of global consumption-based emissions (i.e. emissions beyond the city borders). If we can connect nature in our cities to broader issues of resource use and consumption globally, we may start to alter people’s lifestyle choices relating to diet, travel and recreation.

Fostering this connection to nature will require awareness-raising, education, better policy-making, funding and citizen and community participation. It requires broad movements of people in formal and informal roles, exerting influence and taking action where they can – this could be a teacher in a forest school, a policy-maker in a city administration, a lead designer pushing for a more nature-rich development masterplan or a street artist facilitating a community urban greening project.

Connecting these people can be powerful. In cities there are always opportunities to expand green spaces, improve the management of existing green spaces and improve connectivity between these spaces. There is always a fresh route to walk or a new spot to watch the sunset. There is always a community project looking for a funder; and a funder looking for a community project – often, just the links are missing.

People identify with and are proud of the city where they choose to live. Cities and Mayors are also globally networked. Where an initiative is seen to deliver benefit in one city, there is a good chance it will be replicated and shared through the many networks that already link city dwellers around the world.

Recognizing this opportunity, the World Economic Forum is collaborating with the Government of Colombia on a new global initiative to support city governments, businesses and citizens around the world to create an urban development model that is in harmony with nature: BiodiverCities by 2030. The initiative has convened more than 30 global experts and practitioners and aims to combine the latest research with practical solutions to develop a shared structure to integrate cities with nature.

One city that will undoubtedly be a source of inspiration for the commission is London. London was declared as the World’s first National Park City in July 2019, after a six-year, citizen-led campaign. The National Park City concept is now embedded in all the strategic planning documents of the Greater London Authority (GLA) and has significant business and citizen support.

The London National Park City is described as a place, vision and city-wide community acting together to better people’s lives. It is already stimulating new urban greening and community projects, events and festivals, and there are now 110 sponsored London National Park City Rangers – one or more for each of London’s 32 Boroughs.

The National Park City Foundation together with city partners, World Urban Parks and Salzburg Seminar, has recently published a journey book for other cities aspiring to become National Park Cities. The process set out is interesting: inspired by London’s campaign, it doesn’t require a detailed baselining of species diversity or an inventory of the city’s green spaces – although these things are important; instead it is about creating a shared identity, inspiring people with a bold and positive vision, winning support, being disruptive and nurturing a way of thinking that is local, large-scale, long-term and holistic.

The application process is designed to test whether a city’s application to become a National Park City is visionary, inclusive and supported enough and whether the organization is capable of driving the desired long-term change. It is about building a movement to make life in the city better – for people and nature.

World Urban Parks has set a challenge for 25 National Park Cities by 2025. Twenty cities have already taken their first tentative steps – why not? What if all cities were greener, healthier, wilder and fairer?

*Director for Energy and Climate Change, Arup Group

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer