by David Duong, Neha Rana and Riya Master*

Air pollution is a silent killer. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 9 out of 10 people breathe air containing high levels of pollutants, resulting in 7 million deaths per year.

While many countries have been making active efforts over the past decade to reduce harmful emissions, the clean air crisis has highlighted a dismal reality: the biggest polluters are the least impacted by their environmental waste. As they continue to reap the economic benefits of polluting industries, underserved and underrepresented communities have faced the brunt of the consequences.

Clean air is an increasingly expensive amenity

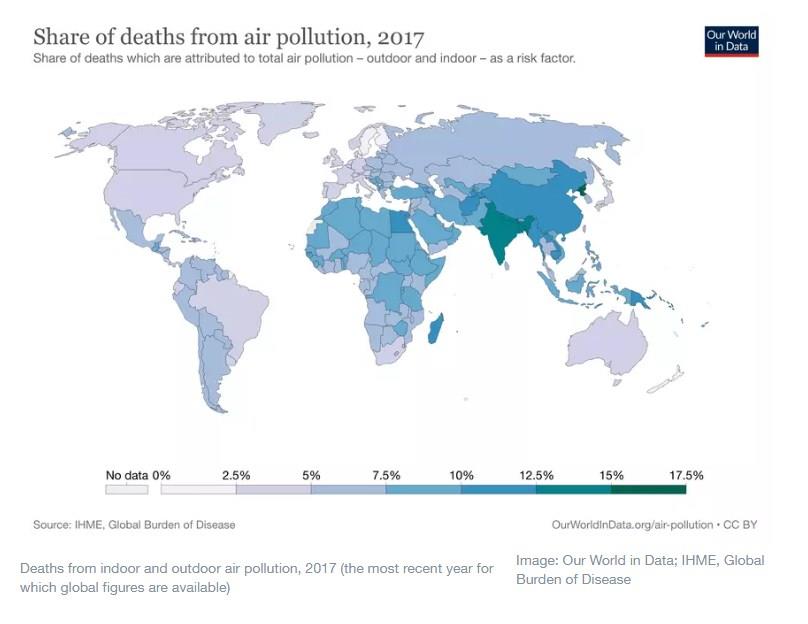

Air pollution exacerbates existing inequities, including health disparities. Indeed, according to WHO research, more than 90% of air pollution deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, while access to clean air is heavily concentrated at the top of the socioeconomic pyramid. In other words, the poor breathe dirtier air.

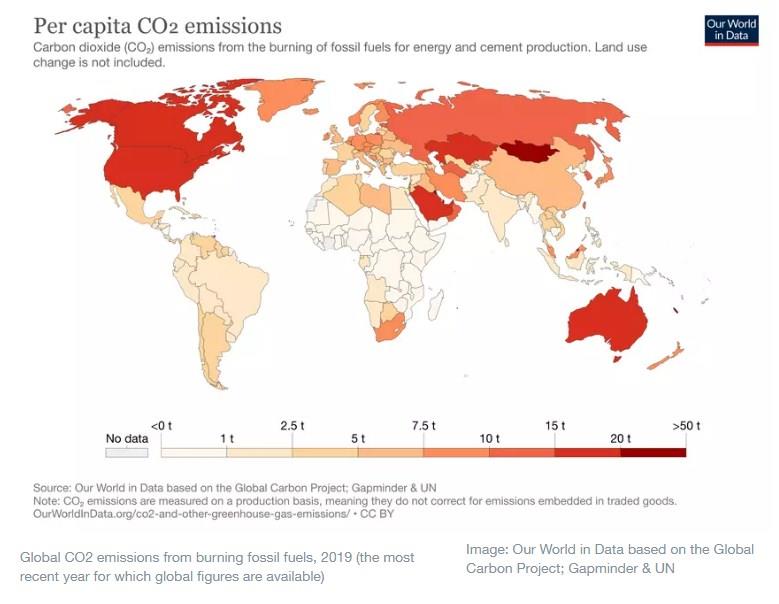

Further, the impacts of climate change are often less immediate for those countries with the highest greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Research shows that, out of the 36 highest emitting countries, 20 are among the least vulnerable to climate change. Meanwhile, 11 of the 17 countries with the lowest GHG emissions are among the most vulnerable to climate change.

As more attention is given to the detrimental effects of air pollution and climate change, air quality is beginning to improve - but only for certain communities. This is not due to the inadequacies of one group or the superiority of another, but the unequal distribution of air pollutants in marginalised communities.

Certain communities are struggling to breathe

In the US, a stark line between race and air pollution can be drawn. Research has shown that white Americans are the greatest contributor to emissions, but experience 17% less air pollution versus their consumption. On the other hand, Black and Hispanic populations respectively experience 56% and 63% more air pollution relative to their consumption. This may be largely due to racial segregation and pollution sources being located near historically marginalised communities.

This is certainly the case in parts of Europe. In the Spanish Basque Country, for example, neighbourhoods with low socioeconomic status are six times more likely than their high-income counterparts to be closer to polluting industries. More generally, 20% of self-reported health disparities in Europe are connected to a lack of green space, neighbourhood conditions and air pollution. The WHO credits the formation of this so-called “environmental underclass” to the combination of environmental health inequity and other negative health pressures.

Other parts of the world present similar examples of unequal access to clean air. In sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, the use of solid fuels like wood and charcoal for heating, lighting and cooking among low-income households results in high rates of air pollution in poorly ventilated homes. Approximately two-thirds of children in the region grow up in homes that rely on solid fuels. High exposure to particulate matter emitted by such fuels can cause premature death from heart disease, stroke, pneumonia, and cancer.

How to tackle the clean air crisis

We need to tackle the environmental, health, and social aspects of this multifaceted issue. Without real, equitable progress to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and curb climate change, only the wealthy will hold the economic right to breathe clean air. By 2050, clean air could truly become the new global currency.

Both individuals and institutions can do a lot to combat this problem. Making everyday lifestyle changes such as riding public transportation or cycling to work can contribute to reducing GHG emissions. Refusing single-use plastics can also help. Supplementing these efforts with dietary changes such as cutting down on meat and dairy consumption and eating locally grown and sourced foods take the solution one step further.

However, these individual lifestyle choices must be met with strong, coordinated national and international action to alleviate the inequitable burden of air pollution on lower socioeconomic communities. Governments and sovereign nations need to place strict limits on oil companies, cap the gases large corporations can emit annually, and advocate for fuel subsidies for homes without gas and electricity. Richer countries and those with a larger carbon footprint need to help limited-resource countries. Individuals should contact their representatives to push for more green initiatives and hold governments accountable for air quality at home and around the world.

Breathing clean air is a human right and clean air should not be monetised. Our world and the air we breathe are a shared resource for all. There should be no hesitation to act or cost too great to protect and restore our air and our environment. We have less than a decade to save our planet and the time for action is now.

*Director, Program in Global Primary Care& Social Change, Harvard Medical School and Undergraduate Research Fellow, Harvard Medical School and Undergraduate Research Fellow, Harvard Medical School

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer