by Emily Pidgeon*

Collectively, the mangrove trees that cling to coasts throughout the tropics may well be the most important ecosystems on Earth.

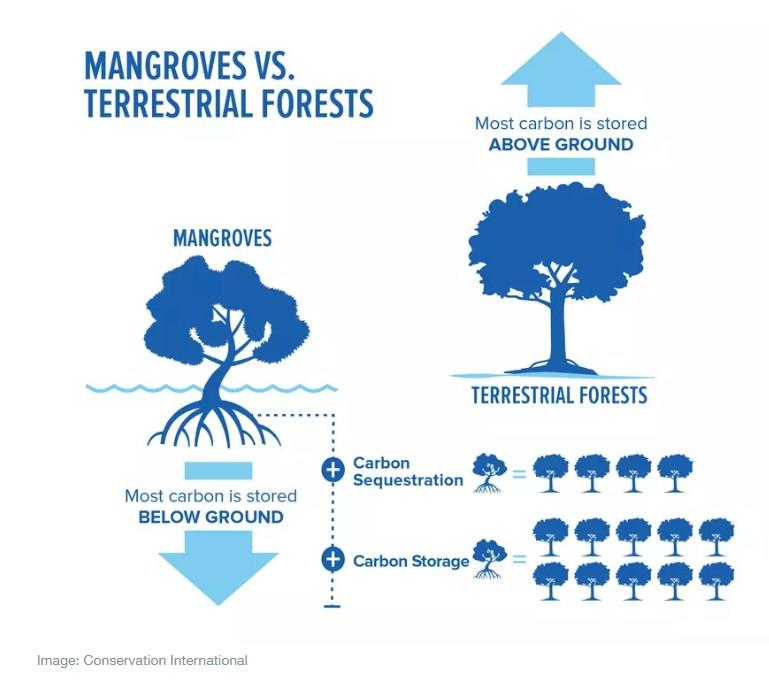

Locked in the mud of these unique tidal forests is thousands of years’ worth of accumulated carbon: a single square mile of mangrove forest holds as much climate-warming carbon as the annual emissions of 90,000 cars.

Mangroves protect coastlines, protect biodiversity and protect local livelihoods: communities that live among healthy mangroves benefit immeasurably from the upsides that mangroves provide — from buffering waves and storms to providing a nursery for fish, crab and clam species that are crucial parts of coastal diets and local livelihoods.

Yet humanity has failed to protect these forests.

The global economic calculus that makes mangroves more valuable dead than alive has devastated them. Nearly half the world’s mangroves have been lost in just the past century, cleared for fish farms, for development, for firewood.

And the short-term payoff of clearing a stretch of mangroves pales next to the impact on the climate: The carbon footprint of a steak and shrimp dinner — were it to come from shrimp farms and pasture formerly occupied by mangroves — is the same as driving a small car across the continental United States, a 2017 study found.

Now, a new effort could be the key to saving them.

On the mangrove-rich Caribbean coast of Colombia, Conservation International has been helping to lead a project that flips the economic script that drives the destruction of mangroves: It is the first mangrove conservation project to be issued carbon credits under the widely adopted Verified Carbon Standard.

This project, called Vida Manglar (’mangrove life’ in Spanish), a joint collaboration between the private sector, civil society and local organizations and authorities, is the first to adequately measure and value ’blue carbon’ — that is, the carbon stored in coastal ecosystems such as mangrove forests. Until now, the inability to do this has effectively shut mangroves out of carbon markets, precluding efforts to flip the economic script that promotes the destruction of mangroves, and depriving coastal communities of potential income in the process.

Uniquely, this project accounts not only for the carbon that mangrove trees store in their trunks and leaves, but also the carbon they sequester in their soils. In most terrestrial forests, soil is typically ignored because it only contains a small proportion of the total of carbon. But in coastal wetlands like mangroves and marshes, soil is the most significant source of carbon in the ecosystem. Ignoring the soil, essentially, means leaving money on the table.

This project represents a sea change in how humanity relates to ’blue carbon’ ecosystems: Commitments made to keep these mangrove forests intact can be purchased and traded on the global market to compensate for carbon emissions made elsewhere in the world. And as pressure grows on companies to account for their impacts on nature, carbon offsets — in short, nature itself — can now become a larger part of the solution.

At the same time, such initiatives assure the durability of the countless other services that mangroves provide — as nurseries for untold species of marine life, as linchpins of food security and incomes for local people, as natural barriers against climate impacts such as stronger storm surges. For this reason — as the new IPCC-IPBES report notes — investments in mangroves go far beyond simply even carbon stored: They are investments in biodiversity, in local communities, in climate justice.

The future of carbon markets, surely, is blue.

*Vice-President, Ocean Science and Innovation, Conservation International

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer