by David Antonioli*

A decade ago, a stretch of land in Kenya became the foundation for a new source of finance with the potential to save the world’s forests: carbon credits.

The premise is simple. Forest countries and communities have historically faced intense economic and political pressure to cut down trees for logging, mining and industrial agriculture, releasing millions of tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere in the process. They need an alternative – more specifically, a tangible incentive – to preserve and restore their forests instead of cutting them down.

Enter the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS). Under the VCS, proponents can propose and implement a project to protect a forest: for example, hiring community members to patrol it, building fire lines to prevent the spread of wildfires, and working with farmers to enhance agricultural productivity, which reduces pressure on the forest. The impact is compared against what would have happened in the absence of the project, and carbon credits are issued: one for every tonne of CO2 that would have otherwise been released.

These carbon credits can be sold to governments, companies or individuals seeking to complement their internal emission reductions and to further decrease their carbon footprints. Finance from the sales is channeled to forest countries and communities, providing alternative livelihoods for people who until then had relied on depleting the forest cover. This finance also supports new jobs, wildlife protection, education, clean water and other initiatives that seek to transform the local economy away from reliance on the forest.

The results speak for themselves. Keeping carbon in the forest becomes an economically attractive option. By the end of 2020, 77 projects for “reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation” (REDD) were registered under the VCS and 185 million credits were issued.

But with a football field of tropical forest being lost every six seconds, the results to-date remain a mere drop of rain in an otherwise empty bucket.

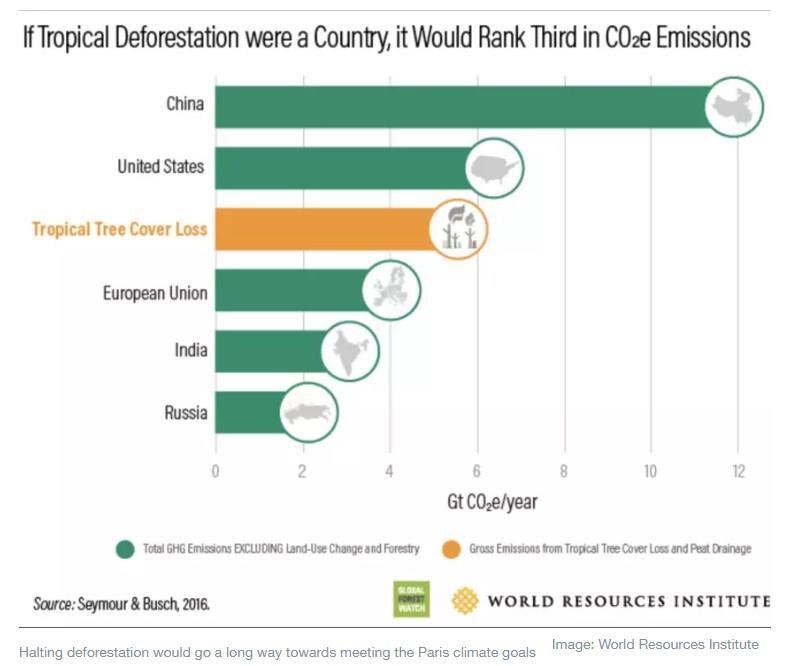

Programs to stop deforestation need to be drastically scaled up. The current decline in tropical forest cover needs to be quickly turned around if we are to reach the Paris Agreement’s goal of keeping global warming to below 1.5°C. The emission pathways set out by the IPCC for this goal are already challenging enough: meeting the 1.5°C target requires reducing deforestation by 77%.

Scaling up requires sufficient and ongoing finance from multiple sources over multiple years. The incentive to preserve forests can be effective when the prospect of funds is real and when payment is contingent on demonstrating that forest carbon stocks are being properly preserved. The incentive to clear forests can outlive these other incentives if the funding source runs dry.

Public and private sector investment needs to move more firmly into this space. Corporates, propelled by fresh commitments to carbon neutrality and net-zero emissions, need to source credits on the voluntary market to compensate for whatever low levels of internal emissions remain or for upstream and downstream emissions they cannot fully control. Some regulatory markets are now also allowing companies to use carbon credits from REDD projects to meet their compliance obligations.

At Verra, we believe that the future of REDD+ (the ’+’ stands for ’conservation of forest carbon stocks, sustainable management of forests, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks’) lies in integrated systems that leverage the strengths of jurisdictional and project-based approaches.

Governments are best placed to create enabling environments and to implement policy measures to protect forests. These can establish a baseload of conditions for private sector investment to support specific projects within these jurisdictions. Project developers can be nimbler and more effective in delivering services to local communities and actors and in addressing local drivers of deforestation, while building resilient alternative livelihoods that don’t rely on cutting down the forest.

We have spent the last two years revising—and just published—the Jurisdictional and Nested REDD+ (JNR) framework to enhance ambition while harmonizing the accounting of emission reductions at the project level with government accounting. This ’nesting’ of REDD+ projects into jurisdictional accounting means that they can be integrated into government programmes while using jurisdictional deforestation rates for the broader area to determine project baselines. This not only eases the accounting of project-specific impacts; it also enhances consistency by ensuring the same data and methods are used across the region, and by dealing with the real risk that emissions may ’leak’ from one project area to other forests in the same jurisdiction.

Ten years in, REDD+ crediting has proven its worth in harnessing finance to tackle one of the most intractable climate problems we face while making real progress on sustainable development at the local level. But we remain far from the scale and investment we need to turn this problem around and make the fight against deforestation help usher in the global net-zero emissions by 2050 that the Paris Agreement demands.

At Verra, we are busy creating the conditions to rally investment in this fight and the voluntary carbon market. We are forging a path toward credible and achievable opportunities to impact on deforestation and forest degradation, working hand-in-hand with local forest communities, jurisdictions and donor governments. One decade old, much growth still remains.

*Chief Executive Officer, Verra

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer