by Shivani Taneja, Paul Mizen and Nicholas Bloom*

One potentially long-term consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic is the new normal of working from home (WFH) – and its effects are not the same across all workplaces (Adam-Prassl et al. 2020). Using a new online survey, we collect data from a randomly selected sample of 5,000 UK working adults within four age brackets of 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-65, during January and February 2021. All participants had earnings more than £10,000 per year, to screen out part-time workers.

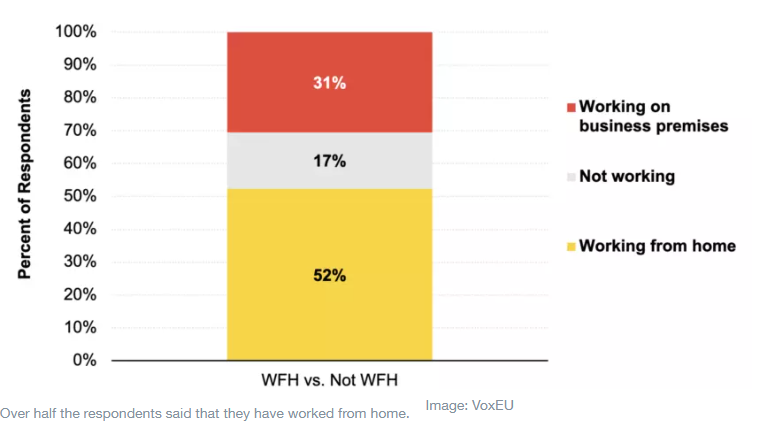

Figure 1 shows that 52% of respondents are currently WFH. Only 31% of the respondents were working on business premises, while 17% of respondents were not working. Thus, a larger proportion of people are WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to those working on business premises, and as others have discovered WFH has buffered the impact of COVID-19 (Adam-Prassl et al. 2020).

This is a slightly higher figure than data from the Decision Maker Panel, which indicated about 41% WFH in this period. Partly this reflects the impact of the second lockdown and partly we may be sampling more workers from occupations with a higher share of tasks that can be done from home (Bartik et al. 2020, Dingel and Neiman 2020).

Figure 1 How often do you work from home (February 2021)?

Notes: Data are from two surveys of 4,809 UK residents, that Prolific carried out in January and February 2021 on behalf of the University of Nottingham and Stanford University. We reweighted the sample of respondents to match the Labour Force Survey figures by age, gender, and education.

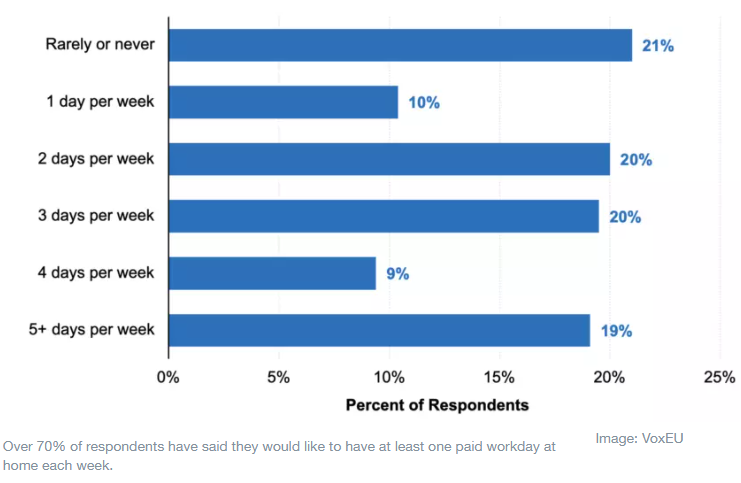

Furthermore, we asked the respondents the following question “After COVID, in 2022 and later, how often would you like to have paid workdays at home?”. Figure 2 shows the percentage of respondents that would prefer to have paid workdays while working remotely after the pandemic. From the figure, approximately 20% would like to work remotely at the polar extremes – none or all working days – and about the same proportion would settle on two or three days per week. Fewer want to have one day at home or at work.

Figure 2 In 2022, how often would you like to have paid workdays at home?

Notes: Data are from two surveys of 4,809 UK residents, that Prolific carried out in January and February 2021 on behalf of the University of Nottingham and Stanford University. We reweighted the sample of respondents to match the Labour Force Survey figures by age, gender, and education.

So, post COVID, British employees want to retain WFH for about two days a week, but there is a huge variation in preferences. This is going to cause headaches for employers – do they let employees choose how many days to WFH but have meeting and events with mixed-mode, which is known to be hard. Worse still those WFH may end up suffering long-run in terms of promotions, which would be a major issue for diversity if certain demographics, like women with young kids, opt to WFH more and miss out on promotions. Or instead do firms force all employees to choose to WFH for 2 days a week, which is about the middle point in preferences, overriding individual preferences? Managers are going to face these tricky issues as we return to offices.

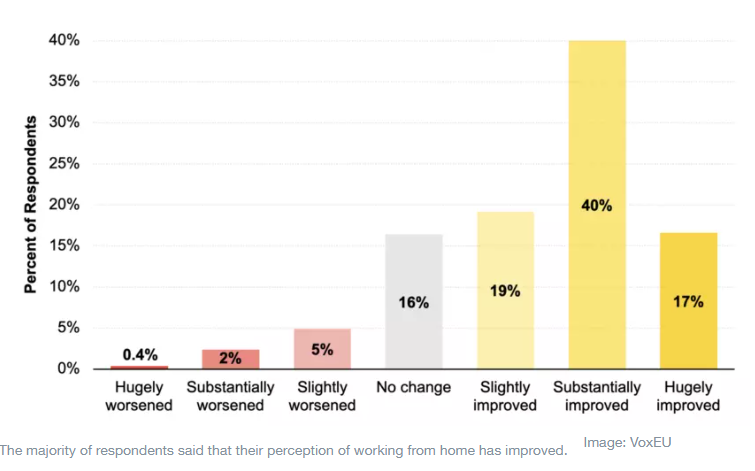

According to Barrero et al. (2020b) using US data, the stigma of WFH has diminished since the pandemic began. To shed light on the stigma associated with WFH for UK residents, we ask the following question in our survey: “Since the COVID pandemic began, how have perceptions about working from home changed among people you know?” Figure 3 shows that 40% of the respondents in the UK reported substantially improved perceptions about WFH and 17% respondents reported hugely improved perceptions. Only a small percentage of 16% showed no change in their perceptions on remote working. Thus, from these results, we find that a total of 76% of the respondents have reported an improvement in the perceptions associated with WFH in the UK, consequently proving that the stigma related to remote working has diminished. Perception may also pick up the perceived costs or benefits of WFH relative to preconceived ideas, and in this respect WFH turned out to be better than expected.

Notes: Data are from two surveys of 4,809 UK residents, that Prolific carried out in January and February 2021 on behalf of the University of Nottingham and Stanford University. We reweighted the sample of respondents to match the Labour Force Survey figures by age, gender, and education.

The impact of WFH on employees’ productivity

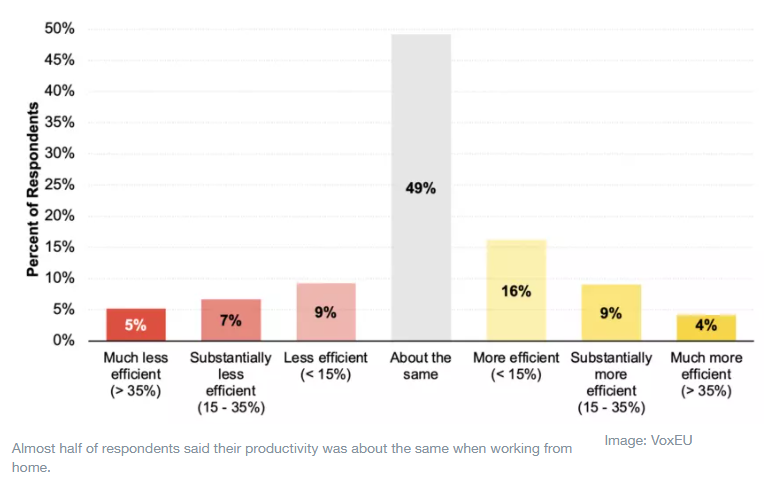

Figure 4 shows that while there is a spread of opinions on this, on average employees consider they are about 2% more efficient when working from home. Certainly, there is no evidence that WFH is substantially less efficient, the big fear before the pandemic. As such this ability to work from home during the pandemic has been critical to keep the economy running while reducing infection rates.

This combination of employee desire to WFH shown in Figure 3 and the positive productivity impact in Figure 4 has led firms to consider hybrid models of working in which staff split their time between the office and home (Financial Times, 28 February). Staff surveys by major firms such as PwC, Lloyds, Barclays, BT, Aon, and Virgin Media suggest UK staff prefer a hybrid rather than a full return to the office. Three quarters of medium sized firms are cutting back on office space and letting their spare offices according to a survey of 405 executives (Financial Times, 4 March). Office construction has fallen from 4.32m sq ft to 3.61m sq ft year on year, and vacancies have risen. Hence, we conclude this surge in WFH is here to stay.

Figure 4 How has your productivity when working from home turned out?

Notes: Data are from two surveys of 4,809 UK residents, that Prolific carried out in January and February 2021 on behalf of the University of Nottingham and Stanford University. We reweighted the sample of respondents to match the Labour Force Survey figures by age, gender, and education.

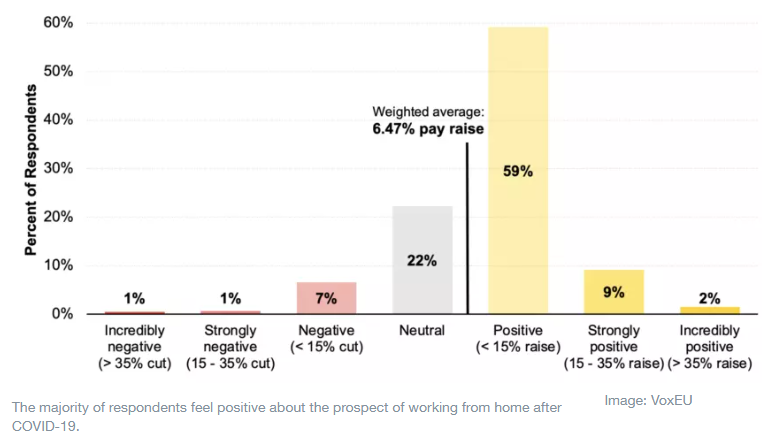

This rise in WFH looks like it will generate a long-run benefit to employees in terms of a valuable perk. As shown in Figure 5 a large proportion of respondents felt positive about the prospect of WFH after the pandemic, with the average employee reporting that WFH for 2 days a week was a perk equivalent to about 6% of earnings. As such this shift to working may be one of the few upsides of the pandemic. However, this will also increase inequality, since higher earning employees are more likely to get to WFH post-pandemic.

Figure 5 After COVID, how would you feel about working from home two or three days a week?

Notes: Data are from two surveys of 4,809 UK residents, that Prolific carried out in January and February 2021 on behalf of the University of Nottingham and Stanford University. We reweighted the sample of respondents to match the Labour Force Survey figures by age, gender, and education.

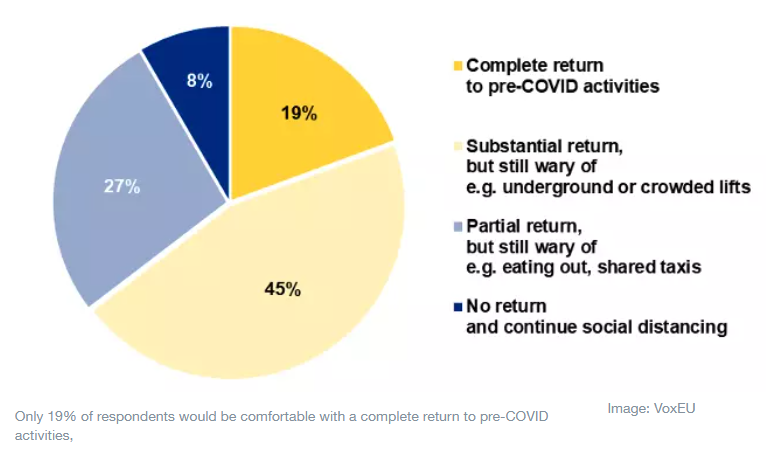

Figure 6 shows the views of the respondents on social distancing after a vaccine is widely available. In our survey of UK employees only 19 per cent reported they would fully return to all pre-COVID activities, highlighting how long the impact of COVID will be on individuals attitudes, with over 80% reporting issues with crowded tube trains and lifts.

Figure 6 Views on social distancing if a COVID vaccine is approved

Notes: Data are from two surveys of 4,809 UK residents, that Prolific carried out in January and February 2021 on behalf of the University of Nottingham and Stanford University. We reweighted the sample of respondents to match the Labour Force Survey figures by age, gender, and education.

Even though in the UK some uncertainty remains over the timeline of the returning to workplaces, it seems certain that many workers will continue to work from home long after the end of the pandemic.

*Research Fellow, School of Economics, University of Nottingham and Professor of Monetary Economics and Director, The Centre for Finance, Credit and Macroeconomics and Professor of Economics , Stanford University

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer