by Frank Jotzo and Paul Burke*

Putting a price on carbon should reduce emissions, because it makes dirty production processes more expensive than clean ones, right?

That’s the economic theory. Stated baldly, it’s obvious, but there is perhaps a tiny chance that what happens in practice might be something else.

In a newly-published paper, we set out the results of the largest-ever study of what happens to emissions from fuel combustion when they attract a charge.

We analysed data for 142 countries over more than two decades, 43 of which had a carbon price of some form by the end of the study period.

The results show that countries with carbon prices on average have annual carbon dioxide emissions growth rates that are about two percentage points lower than countries without a carbon price, after taking many other factors into account.

By way of context, the average annual emissions growth rate for the 142 countries was about 2% per year.

This size of effect adds up to very large differences over time. It is often enough to make the difference between a country having a rising or a declining emissions trajectory.

Emissions tend to fall in countries with carbon prices

A quick look at the data gives a first clue.

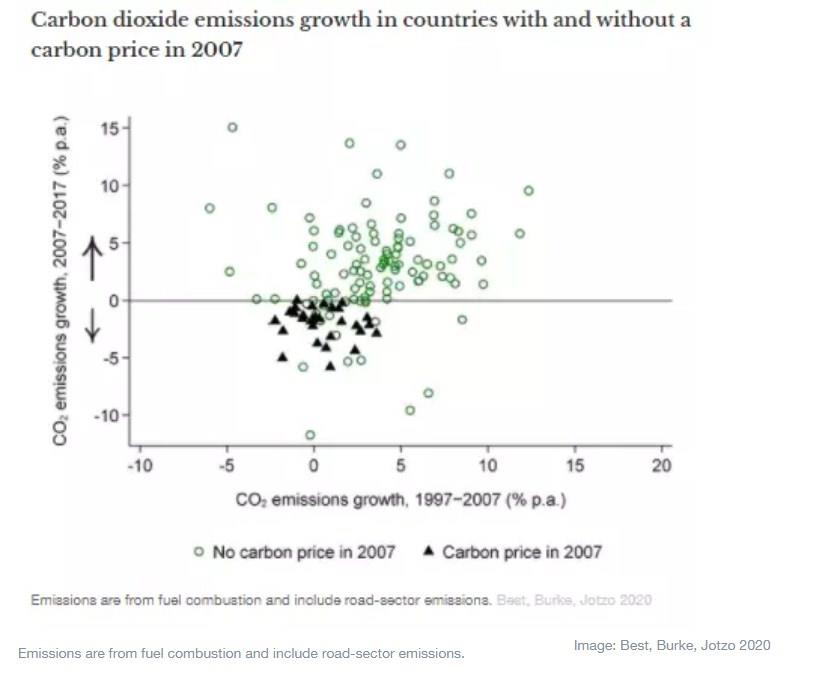

The figure below shows countries that had a carbon price in 2007 as a black triangle, and countries that did not as a green circle.

On average, carbon dioxide emissions fell by 2% per year over 2007–2017 in countries with a carbon price in 2007 and increased by 3% per year in the others.

The difference between an increase of 3% per year and a decrease of 2% per year is five percentage points. Our study finds that about two percentage points of that are due to the carbon price, with the remainder due to other factors.

The challenge was pinning down the extent to which the change was due to the implementation of a carbon price and the extent to which it was due to a raft of other things happening at the same time, including improving technologies, population and economic growth, economic shocks, measures to support renewables and differences in fuel tax rates.

We controlled for a long list of other factors, including the use of other policy instruments.

It would be reasonable to expect a higher carbon price to have bigger effects, and this is indeed what we found.

On average an extra euro per tonne of carbon dioxide price is associated with a lowering in the annual emissions growth rate in the sectors it covers of about 0.3 percentage points.

Lessons for Australia

The message to governments is that carbon pricing almost certainly works, and typically to great effect.

While a well-designed approach to reducing emissions would include other complementary policies such as regulations in some sectors and support for low-carbon research and development, carbon pricing should ideally be the centrepiece of the effort.

Unfortunately, the politics of carbon pricing have been highly poisoned in Australia, despite it being popular in a number of countries with conservative governments including Britain and Germany. Even Australia’s Labor opposition seems to have given up.

Nevertheless, it should be remembered that Australia’s two-year experiment with carbon pricing delivered emissions reductions as the economy grew. It was working as designed.

Groups such as the Business Council of Australia that welcomed the abolition of the carbon price back in 2014 are now calling for an effective climate policy with a price signal at its heart.

Carbon pricing elsewhere

The results of our study are highly relevant to many governments, especially those in industrialising and developing countries, that are weighing up their options.

The world’s top economics organisations including the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development continue to call for expanded use of carbon pricing.

If countries are keen on a low-carbon development model, the evidence suggests that putting an appropriate price on carbon is a very effective way of achieving it.

*Director, Australian National University and Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer