by Ilona Szabo de Carvalho, Robert Muggah and Brodie Ferguson*

The Amazon Basin is approaching a dangerous tipping point. Within a few years the world’s largest tropical forest could experience a ’die-back’ that would not just affect South American countries, but deal a fatal blow to global efforts to reduce carbon emissions. It is no secret who is to blame. The principal culprits are the constellation of industries and individuals responsible for illegal deforestation. More than 90% of all deforestation is illicit, which means that tackling environmental crime is key to progress on climate action.

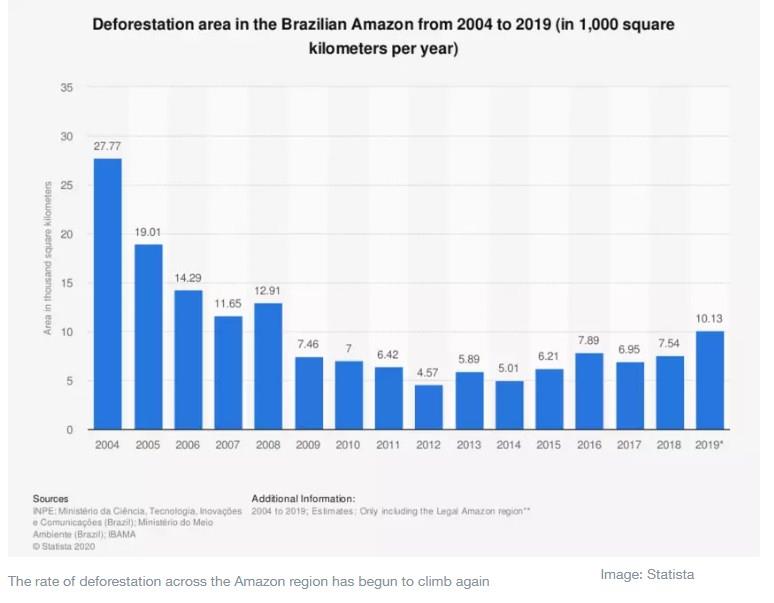

The sheer scale of devastation of the Amazonian forest is literally breathtaking. Despite international outrage and condemnation, deforestation rates jumped 55% across the region in the first four months of 2020 compared to the same period last year. Virtually every scientist studying the Amazon believes there is no good reason to cut a single tree down - what is required is to enact zero-deforestation policies, make existing land more productive and to restore degraded soil.

The consequences of rampant deforestation are overwhelmingly negative. Every hectare that is cleared means that parts of the overall ecosystem are degraded and cease to function. Degradation reduces the efficiency of forests, eroding their ability to generate rain. Without rain, evapotranspiration declines: the Amazon’s infamous ‘flying rivers’ will simply cease carrying water throughout the region. This has dangerous implications not just for the 30 million people living in the Amazon, but also for food production and water availability for the nearly 300 million living in cities throughout the eight countries that form the Amazon Basin.

A variety of actors

Governments across the region typically blame smallholder farmers involved in subsistence food production for the destruction of the Amazon – but the reality is far more complex. Study after study shows that large agribusiness and beef-producing companies and their local suppliers are responsible for most forest clearances. Ultimately, deforestation and degradation are perpetrated by a variety of actors, both both legal and illegal, and connected to domestic and global supply chains.

Illegal deforestation and degradation occur in several ways. The most obvious is illegal land invasions followed by selective logging and the clearance of forest for commercial agriculture and ranching. Another modality involves both lawful and wildcat mining, mostly for gold, which has lasting effects on local ecosystems, biodiversity and human health. Forests are also affected by wildlife trafficking, fuelled by unrelenting demand for rare birds, reptiles and mammals around the world. Many governments, law enforcement organizations and environmental groups treat these phenomena in isolation, yet there is evidence that many of the underlying networks involved in these criminal activities are connected.

In partnership with Interpol and InSight Crime and collaborating with organizations such as ISA and MapBiomas, the Igarape Institute is tracking the networks driving environmental crime across the Amazon Basin. To disrupt these activities it is essential to expose the actors involved and the ways in which illegally sourced products are flooding global supply chains. Many of the criminal organizations involved in illegality are themselves enabled by legitimate businesses alongside corrupt government officials, including police officers, notary clerks, customs officials and politicians. The proceeds are creatively laundered, such as by rolling ill-gotten gains into legitimate farmland or mixing illegally extracted gold with legal exports. Environmental criminals are tech savvy, deploying cryptocurrencies, drones and satellite technologies to evade the law.

One reason why fighting environmental crime is so tricky is because of the way ostensibly ’legal’ actors and activities are intertwined with ’illegal’ ones. Take the case of the energy and infrastructure sectors, which are often rife with land speculation and dodgy deals. Claiming to be promoting “development”, well-placed politicians, businessmen and civil servants make a killing while the Amazon burns.

The idea that the Amazon constitutes a vast empty hinterland to be occupied, developed and modernized goes back to the mid-20th century. Armed forces across the region are especially defensive about outside interference and are heavily involved in ‘development’ schemes across the region – yet armies are struggling to protect the rainforest.

Environmental crime is also powered by globalization. The rising demand for beef and soy from China, the US, Europe and emerging markets has contributed to a boom in intensive agriculture and ranching. Fluctuations in the global price of precious metals have likewise triggered a clandestine gold rush.

Working together

There is negligible regional cooperation around eradicating environmental crime. A big reason for this is low levels of trust between governments in the region (and the fact that some corrupt officials benefit from illegal activities). Domestically, public agencies rarely coordinate effectively to locate, investigate, prosecute and penalize environmental crimes which explains the rampant impunity.

Notwithstanding previous multi-agency initiatives to slow deforestation and recent innovations such as the Council for the Amazon in Brazil, the political reluctance to boost forest conservation efforts has impeded the work of prosecutors and other law enforcement agencies. There is also inadequate collaboration between government bodies and non-governmental organizations, despite the growth of environmental activism across the region.

Complicating matters, the resurgence of nationalism and populism has undermined the potency of regional initiatives such as the Amazon Treaty Cooperation Organization (ATCO), which still mostly exists on paper. With the exception of periodic regional meetings, there are still comparatively few dedicated efforts to promote joint initiatives to tackle environmental crime. For its part, the Organization of American States (OAS) has a mission in Colombia to support the peace process and has worked on specific issues such as sustainable transboundary water management, but does not address security or environmental issues in the Amazon systematically.

More positively, a number of private sector groups are beginning to step up where the public sector has failed to lead. Last year, more than 250 global investors with $17.7 trillion in assets called for companies operating in the Amazon Basin to meet their commodity supply chain deforestation commitments. Past experience demonstrates that when there are transparent partnerships between public agencies and the private sector, meaningful action to reduce deforestation is possible. Where these pacts are weak, defection is more likely.

Private sector groups are also partnering with tech-proficient non-profit organizations to tackle environmental crime. For example, Rabobank, the largest bank in the food and agribusiness sector and the second highest-ranked Forest 500 financial institution, now integrates the use of MapBiomas (cross-validating land titles, satellite data and government embargoes) into its credit approval process. Large exporters Marfrig and Cofco recently began tracing products to the farm level, employing increasingly cheap tools such as remote sensing, AI and blockchain in order to secure financing and access to foreign markets. Others like Global Witness, Imazon, Global Forest Watch and Trase are likewise stepping up their game.

While these efforts to crack down on environmental crime are positive signs, the world will need much more to pull the Amazon’s forests back from the brink.

*Executive Director, Igarape Institute and Founder, SecDev Group and Igarape Institute and Senior Researcher, Igarape Institute

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer