by Debra Whitman*

As early as February, it was clear that individuals at highest risk for severe disease and death from COVID-19 included people over 60 and those with underlying conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

The danger they face is painfully evident in many nursing homes and other long-term care facilities in which conditions exacerbate the risks. Too frequently, residents share rooms and mix in close quarters, and they have frequent and high-touch physical contact with staff who move from room to room.

Yet in those early days, few countries developed plans to protect the vulnerable, older individuals who rely on assistance in long-term care facilities. In fact, many patients with the virus were transferred into unsafe facilities to ease the burden on overcrowded hospitals.

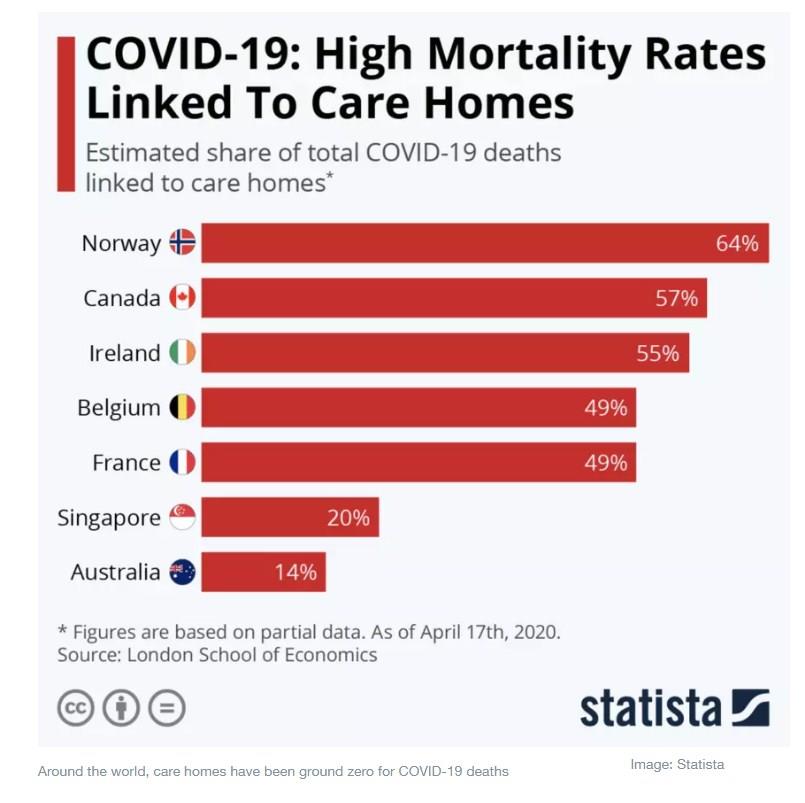

It was a recipe for disaster, and a disaster it has become. In many countries around the world, these facilities have been ground zero for COVID-19 infections and deaths.

In the US, more than 67,000 people in long-term care facilities have died, and more than 375,000 have become infected as of late August. According to the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, more than one in 10 residents of nursing homes in the District of Columbia, New Jersey, Connecticut and Massachusetts has died from the coronavirus. In Europe, up to half of all reported COVID-19 deaths have occurred in long-term care facilities, the World Health Organization reports. In Italy, this grim phenomenon is called the “silent massacre”.

Yet even now, far too many countries still lack adequate plans to stop these infections and safeguard the residents and staff who care for them. This is unacceptable. We can and must do better to protect our parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles who need care. Those who cannot take care of themselves must not be left to die in these settings.

Actions needed to address this problem

What are the steps we can take now? Let’s start with the basics:

1. All facilities need access to PPE, testing and basic infection control

Frequent universal testing, mandatory use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and the ability to quarantine the sick are basic public health requirements. Yet many facilities still lack sufficient access to PPE for staff and residents. Shortages of testing supplies and infrequent testing make it hard to know which residents and staff are carrying – and spreading – the virus.

Once someone tests positive, facilities must be able to separate them from those who remain healthy. Often workers are moving between wards, or residents are moving between common rooms, even after they have been diagnosed.

2. We need to know where the problems areas are

In many places, a lack of transparency in reporting infections has been an issue. Daily, public reporting of cases and deaths would make it clear where the hot spots are and whether a facility is adequately addressing transmission.

3. We need to support connection between the residents and their families

Social distancing and lockdowns cannot become social isolation. Yet loneliness and isolation have become much more common, as residents are often quarantined in their rooms, and family members are not allowed to visit. This is particularly problematic since families provide emotional and social support critical to helping residents maintain their health, wellbeing and safety. Isolation breeds confusion, depression and anxiety. Virtual visitation should be supported in all facilities to help loved ones keep connected.

4. We also need to support the healthcare heroes – the direct care workers – who are often as vulnerable as the residents

At least 500 care workers have died, making this the most dangerous job in America. And yet they are paid extremely low wages. In some cases, staffers must work in multiple facilities to earn a living wage, increasing the risk of transmission.

Despite such risks, workers in many countries do not receive adequate training in how to reduce infections for themselves or residents, according to the OECD. It is no wonder that many facilities are experiencing serious staffing shortages. Yet as the world ages, the need for care workers only rises – and the more professional the jobs, the better the care will be.

Challenges before the pandemic

The challenges faced by long-term care facilities have been exacerbated by COVID-19, but they are not new. Facilities have long faced understaffing, underinvestment, inadequate infection control, a lack of emergency preparedness, and regulatory issues. We need to improve both quality and affordability of care later in life, including for those who are not able to live independently.

My hope is that the horrors of COVID-19 will make us take a closer look at cracks in the broader system. Let me mention two important areas:

1. Financing: Families must be able to afford long-term care

Many countries have not developed comprehensive systems for financing long-term care. Germany and Japan, which have universal long-term care insurance systems in place, are the exception. In the US, however, a family pays on average more than $100,000 for a private room. The federal government only assists those with very low income and assets and who qualify for their state’s Medicaid program.

2. Vision: We must redesign and rethink long-term care facilities from the ground up

At AARP, we have heard from nearly 6,000 family caregivers whose loved ones live in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities about their experiences during this crisis. Their accounts are gut-wrenching and underscore the need for major change.

Our vision is for a system that promotes independence, choice, dignity, autonomy and privacy. It must be fiscally sustainable and affordable both to individuals and the government.

We know that most people prefer to receive care in their homes and communities, where it is often cheaper than in residential settings. Allowing people to be cared for at home would help reduce the risk of contracting COVID-19 or a future virus.

For those who cannot remain at home, smaller facilities seem to have lower transmission rates, and residents report higher satisfaction. As part of the rethinking, we can learn from approaches like the US Green House model, which emphasizes personal dignity and person-centered care.

Working together to transform the system

Tragically high death tolls for older adults during this pandemic have exposed structural deficiencies in long-term care facilities across the globe. I recently shared my thoughts on these issues in a webinar hosted by the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Council on Longevity, which included other experts from around the world.

This is a critical time in the world’s response to COVID-19. As countries begin to ease restrictions, they must act in a way that protects the most vulnerable and treats no one as expendable. Together we can develop a stronger and more resilient system – not just for the next pandemic, but for the next generation.

*Executive Vice President and Chief Public Policy Officer, AARP

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer