by Lutfey Siddiqi*

To quote Singapore’s senior minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam from his national address last month: “The future begins now”. That future will be dramatically different not only for governments and individuals but also for big business and big finance. A silver lining to the devastation of COVID-19 could be the onset of a new era for both stakeholder capitalism and sustainable investing.

The future economy, the future of jobs, education, finance, energy – indeed, the future of everything – have been titles of conferences and committees at national and international levels for over half a decade. What COVID-19 has done is accelerate the disruption already heralded by the Fourth Industrial Revolution and demographic trends, and underscore the urgency required to address systemic vulnerabilities.

The immediate macroeconomic policy response was swift and decisive around the world. So much so that they have seemingly overturned several taboos.

Changing mindsets, challenging ‘sacred cows’ and established habits, and embracing fundamentally different roles are the hallmarks of the post-pandemic world. This applies not only to governments and individuals; it includes the private sector and its role in the recovery process. As the emergency support measures roll off in the coming months, stakeholder capitalism will have to display its relevance and potency.

Stakeholder capitalism and inclusion

It is almost a year since the Business Roundtable, whose members are chief executives of major US companies, issued a path-breaking declaration on the purpose of a corporation: to serve all stakeholders, moving away from shareholder primacy. In the following months, the UN Global Compact, UN Environment programme, the World Economic Forum, OECD, various central banks, and major multinationals stepped up their commitment to mobilise private-sector resources towards the sustainable development goals (SDG). However, there was legitimate skepticism about the sincerity with which companies would back their rhetoric with action. How much of this is window-dressing, tokenism, or impact-washing?

COVID-19 presents a powerful threshold-moment in the alignment of words with deeds. To take two examples from Singapore, both DBS and UBS have made commitments with regards to jobs and skills. Through the Singapore UBS Program for Employability and Resilience (SUPER), the Swiss bank will create 300 new jobs, which is the equivalent of 10% of its workforce in the country. At the same time, South East Asia’s largest bank, DBS, announced its commitment to hiring 2,000 people, at least half of whom will be in new roles.

How are these measures justified from the perspective of return-on-equity when the outlook for earnings is so murky? Members of the C-suite will admit that in the current economic environment, the first instinct is to cut back on hiring and costs in general. However, if you have an entire cohort of fresh graduates coming out of higher education without jobs, that simply cannot be good for business. The self-enlightened realisation is that an economy is a circular flow of income; that flow does not function without adequate demand. In the fullness of time, responding to the social need of the hour is simply good business: stakeholder and shareholder interests converge.

More generally, companies need to help sustain demand for their products. In a world of widening inequality, income flows to those who consume less and save more. Demand must come from new sources – new communities, new regions, and new markets. As a result, inclusion becomes a strategic driver of growth.

For example, the education group Pearson recently issued what it claims to be the world’s first education-linked social bond. The proceeds of £350 million ($458 million) can only be used to deliver online education to “underserved learners and communities, including those from low-income backgrounds, with disabilities and the unemployed”.

Sustainable investing and inclusion

What is true for investee companies is also true for investors of capital. Existing assets and entire asset-classes are saturated, the outlook for returns is low, and interest rates are expected to remain low for an extended period. The wall of money released by quantitative easing needs new destinations. Here again, inclusion is the way out. New securities and asset classes will have to be created. The finance industry now has a commercial and existential impetus to rapidly bring the field of “responsible investing”, green finance, social bonds and so on into the mainstream.

More money should flow into previously excluded sectors with significant impact on the real economy. For example, in some emerging economies, this could mean deeper and wider capital markets, which in turn would foster domestic insurance and pension services. Elsewhere, government support for localised micro and small enterprises could be magnified by crowding in private investors who are looking for new avenues in which to deploy their funds.

Large influential investors such as sovereign wealth funds can lead the way. In recent weeks, Singapore’s GIC has underscored long-term themes such as environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors as well as the importance of bottom-up opportunities versus top-down views.

The largest pension fund in the world, Japan’s GPIF, is also taking a “systems view” of the investment landscape, demanding ESG awareness from all of their asset managers and catalysing inclusion. The fact that GPIF posted record losses of $164 billion in the first quarter of 2020 might suggest that investors of their size have simply run out of opportunities in the current universe of assets. It is in their own interest that they should help expand that universe.

Bandwagon in train

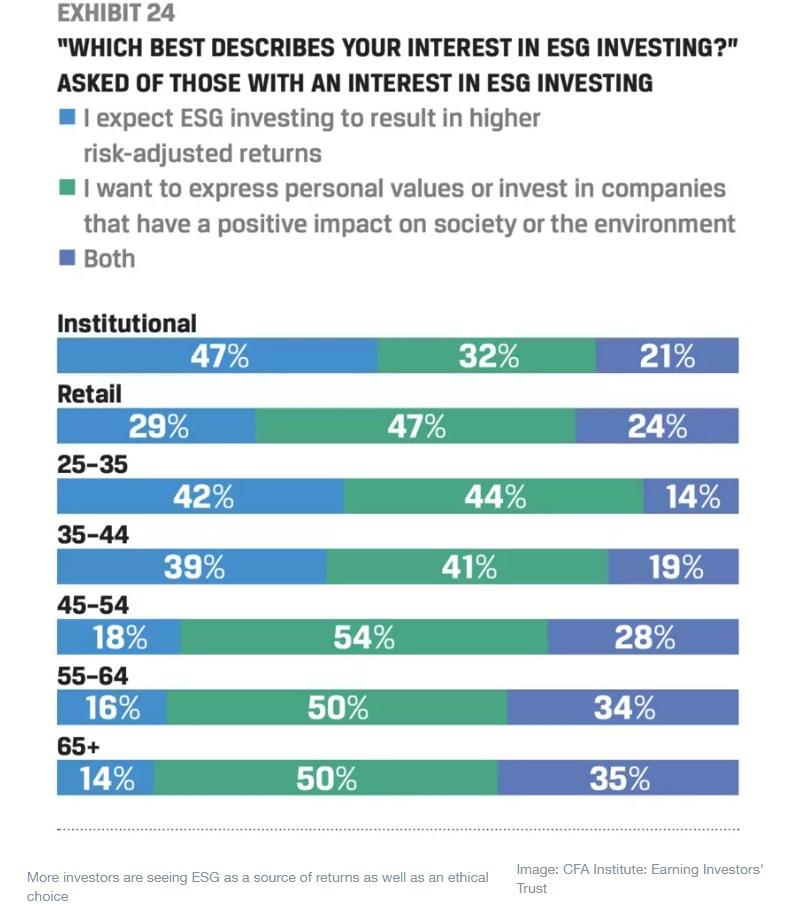

The investment profession is also shaped by customer preferences. The recent trust survey conducted by the CFA Institute shows that increasingly, the beneficial owners of funds wish to see how their returns are generated. They seek greater information, innovation, and influence to make sure that the pursuit of economic value is consistent with their values. Financial advisors and investment managers need to be honest about the long-term outlook of investments so as not to erode trust if and when investment performance falls short of expectations. That dialogue must include ESG factors and sources of material risk such as climate change.

Finally, regulators are also nudging in the right direction. Disclosure directives in Europe, stress tests required by central banks such as the Bank of England, the active ongoing debate about reporting standards – all point towards an inflection point. The ECB President Christine Lagarde has also indicated that the central bank’s direct purchase of assets could be used to pursue green objectives – a first for any monetary authority.

COVID-19 and its consequences should sharpen the convergence of interests between providers of capital, entrepreneurs, and society at large. The bandwagon of stakeholder capitalism and sustainable finance is well and truly in train. As the future unfolds, those not already on it – authentically and materially – risk getting left behind.

*Visiting Professor-in-Practice, London School of Economics and Political Science

**first published in: www.weforum.org