by Morten Olsen*

Jeff Bezos, the CEO of the company millions depended on for deliveries during coronavirus lockdown, is reportedly set to become the world’s first trillionaire. As forecast by business platform Comparisun, his unique status isn’t due to the current crisis. It is based on a continuation of growth trends in Bezos’s net worth over the past five years, which show increases of about 34 percent annually. In other words, it is the latest addition to the eye-popping study in contrasts that the world economy has become.

The growing concentration of wealth at the top has led prominent American politicians on the left, such as US Senator Bernie Sanders, to proclaim that billionaires, by rights, should not exist. How, then, would they account for Bezos’s almost unimaginable prospective wealth?

The global “superstar economy”

Some have chosen to blame crony capitalism. In this analysis, the most fortunate few have co-opted the political system – which was designed to rein them in – with their dollars and influence. Favour-paying on the part of compromised politicians would certainly help explain the penchant for deregulation that has prevailed on both sides of the aisle in Washington, DC in the last 40 years.

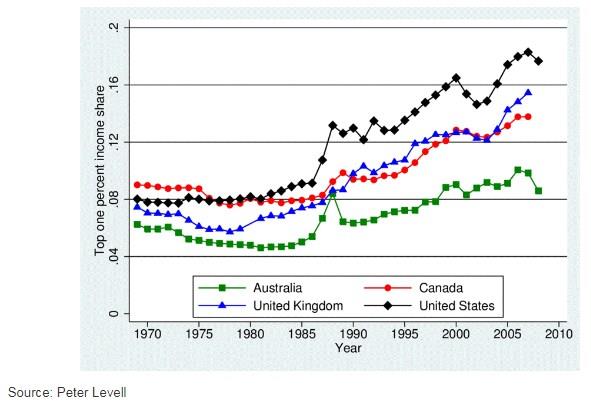

There is a big problem with this theory, however. The general trend towards rising inequality, resulting in more and more goodies jammed into the already bulging pockets of a few “superstars”, is not limited to the United States. It is distinctly seen, though to a lesser extent, in Australia, Canada, China and the United Kingdom among others. Unlike the US, these countries do not have a multi-billion-dollar per year lobbying industry aimed at influencing public policy for the benefit of corporate clients.

Inequality within nations, though, is just the tip of the iceberg. The rise of a few superstars relative to everyone else is a pattern so firmly etched into the broader economy that it seems to show up virtually any way you parse the data. Just look at how the centre of gravity has shifted dramatically upward in a number of industries. In 1982, for example, 26 percent of total ticket sales for live concerts went to the top one percent of music-industry earners; by 2017, the one-percenters’ share had more than doubled to 60 percent. Within the publishing industry’s top ten global bestsellers of the last 50 years, the Harry Potter series – which ranks #3 altogether, right behind The Holy Bible and Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung – has moved more copies than #4-10 combined.

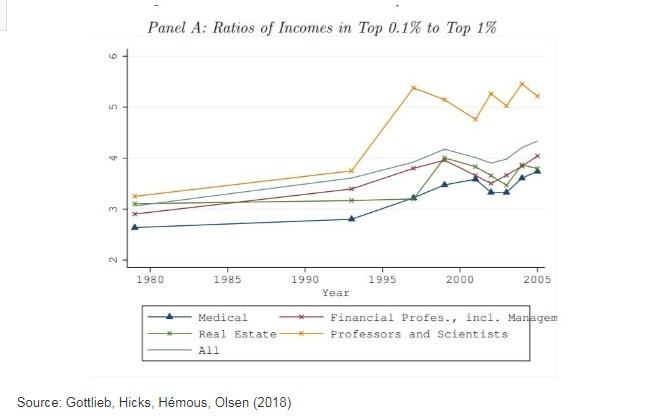

Income gaps between occupations have also grown globally. The difference in wages between, say, an engineer and a schoolteacher is significantly greater now than it was in 1980. Even within certain professional-class occupations paying well above average, e.g. physicians and college professors, the distance between rungs at the very top of the income ladder has increased. In these sectors, inequality has infiltrated the top one percent, elevating the mega-elite 0.1 percent above the rest.

Differences between firms

For salaried employees, enormous pay discrepancies within companies contribute to the overall superstar effect. The galloping increase in CEO salaries since the 1990s, for example, has left ordinary employees in the dust. Far more consequential, however, has been the growth in overall pay gaps between rather than within firms, according to one paper analysing the US labour market from 1978 to 2013.

The authors describe a kind of firm-employee assortative matching not unlike the current trend towards within-class marriage. In an era of lower job security, the best people will flock to thriving companies capable of paying higher wages, pushing successful firms’ performance even higher. Over time, this brain drain becomes a rising tide that lifts all boats for employees of superstar companies, from the frontline to senior management.

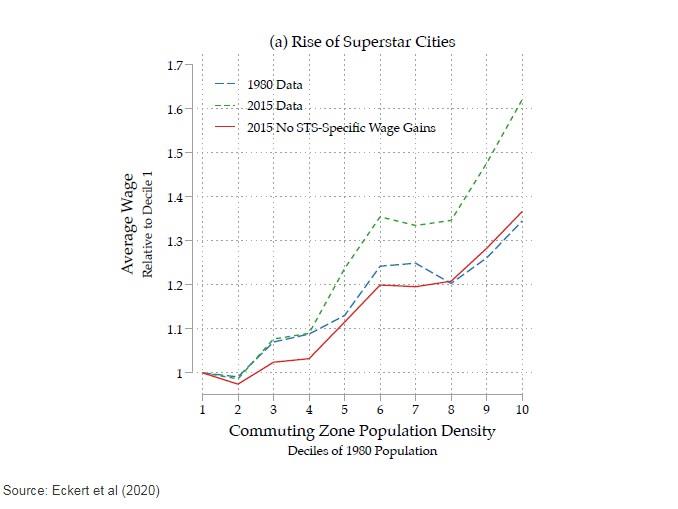

A similar clustering effect has occurred in the developed world’s major cities. London, New York, Copenhagen, etc. have become magnets for talented strivers from their respective nations (as well as expats from abroad), contributing to an economic decline in non-urban areas that can become a veritable death spiral as the tax base shrinks.

Underlying economic changes

With all these dimensions of inequality telling the same basic story, we can speculate that the main drivers must be fundamental to the contemporary economy. Crony capitalism and other types of regulatory capture surely exacerbate inequality. But if all forms of soft and hard corruption were to disappear overnight, the upward distribution of resources would continue, albeit at a lower level. In other words, the underlying system, not its subversion, is at the root of the phenomenon.

Specifically, the combination of globalisation and technological innovation seems to act as an engine for the superstar economy. Professional football supplies a clear example. Digital technology considerably lowered the costs of broadcasting matches internationally, expanding the global fan base for the best clubs (Real Madrid, Barcelona, Manchester United). As a result, local leagues must now compete with the world’s greatest players for the attention of home audiences, which was theirs automatically in the pre-digital era. Stealing the spotlight from smaller competitors not only grants superstar clubs an even bigger platform and more money, but it also enhances their attractiveness to elite footballers in search of a home, further burnishing their relative status through assortative matching.

Similarly, mid-sized manufacturers that would once have had an assured customer base for their finely made, high-end products are losing ground to globalised behemoths. For example, Danish electronics company Bang & Olufsen has struggled to defend its turf against Samsung and others capable of flooding the world market with cheaper yet perfectly serviceable gadgets. The globalised economy, with its enormous returns to scale, rewards the conquest of new markets and erodes the special advantages that protect smaller entrants from overseas competition.

Automation is a part of this story too. A 2019 article co-authored by David Hemous shows how firms’ own incentives – as opposed to external developments such as the sudden availability of new materials or labour skills – explain some of the more curious features accompanying income inequality, including the “productivity paradox” and fluctuations in the relative wages of skilled and unskilled workers. In short, innovation raises demand for low-skilled workers and in turn wages, which incentivises employers to adopt automation as a cost-cutting measure. This obviously promotes income inequality, since white-collar jobs have been far less subject to automation. However, as automation becomes more widespread, its economic impact is diluted. The pay disparity between skilled and unskilled workers to which it contributed begins to grow at a slower rate.

Public policy for the superstar economy

These dynamics create a complex picture for policymakers. A tax on the use of automation equipment, the paper finds, would modestly increase low-skilled wages by encouraging more sparing use of worker-replacing machines. A tax on automation-related R&D would have the same levelling effect initially. As the overall innovation pipeline narrowed over time, however, lower-tier wages would suffer. Recall that economic growth owing to innovation was what hoisted wages to the point that automation became a lucrative option in the first place.

More broadly, governments should recognise that the superstar economy is, to an extent, baked into the capitalist system by now. In a sense, the beneficiaries themselves are not to blame. They are merely capitalising on opportunity, engaging in profit-seeking behaviour as we expect well-run companies to do. Grand gestures such as breaking up superstars into smaller units won’t necessarily level the playing field – although there is no reason for regulators not to look closely at M&A deals wherein monopolies-in-the-making eliminate what little competition they have. Whether, for example, Facebook should have been allowed to buy Instagram is a question well worth asking.

Some are predicting that Covid-19 will change the game profoundly. It is true that the pandemic has disrupted cross-border supply chains, escalated tensions between the two main superpowers and halted international travel for the time being. It remains to be seen, however, whether the globalisation genie can be put back in the bottle. The spoils to be enjoyed by the superstars are too rich and alluring. One can hardly imagine Apple, Samsung et al. opting to pack it in and sell only within their native countries.

As it was before the pandemic, the global economy is a delicate mechanism of tenuously poised weights and counterweights. Wading blindly into that morass could lead to disaster. Perhaps the best response to income inequality is the most simple and direct one: a Scandinavian-inspired redistributive welfare state that does not begrudge the superstars their status, but ensures that some of the proceeds feed back into society at large.

*Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Copenhagen

**first published in: knowledge.insead.edu

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer