by John Mauldin and Mike Roizen

Should you wear a mask in public? This seemingly simple question immediately generates emotional, political, and social anxiety.

It is just one of many provocative questions COVID-19 is forcing upon us. They should be simple, data-driven policy issues but many are not.

Today’s letter is in a different format from the usual Thoughts from the Frontline. As long-time readers know, I am in frequent (and lately almost daily) contact with Dr. Mike Roizen, emeritus head of wellness at the famous Cleveland Clinic, member of the Cleveland Clinic’s leadership team, and author of many books which, thanks to Oprah (he was her doc), have together sold 28 million hard copies. Today we write a joint letter to you. It may be controversial, but that comes with the territory.

Mike and I became online friends over 15 years ago and then he became my doctor and a good friend. He keeps me healthy and I feed his economic information addiction. A perfectly reasonable symbiotic relationship. We have been sharing information on the coronavirus crisis, on which he is an advisor to several state governments.

So today, we’re going to look at some actual data, both medical and economic. Spoiler alert: The unintended consequences of our response may be more threatening than the actual virus, unless we begin changing some things soon.

Double Effect

We’ll start by looking at both direct effects of the coronavirus, and its secondary effects.

The direct effects come from both the virus itself and—critically important—from people avoiding healthcare because they fear exposure to the virus at a healthcare facility. Studies are beginning to show the latter group may be larger than the former.

Then there are secondary health effects related to our response to the virus. These secondary effects are largely due to the economic consequences. We are seeing both “deaths of despair” and health consequences due to changes in the healthcare system, such as closure of some rural hospitals and the rise of telemedicine. The effects are visible, but the absolute data isn’t.

Another thing we don’t fully understand is regional variation. The virus obviously strikes some areas harder than others.

For example, total COVID-19 deaths as of May 28 in Texas, Florida, and California combined were 7,877. Those states have 27% of the US population but so far less than 8% of the COVID-19 deaths. The hospitals of those regions were not taxed, and many ICU beds were empty as elective surgeries were cancelled. Healthcare facilities generally had adequate protective equipment.

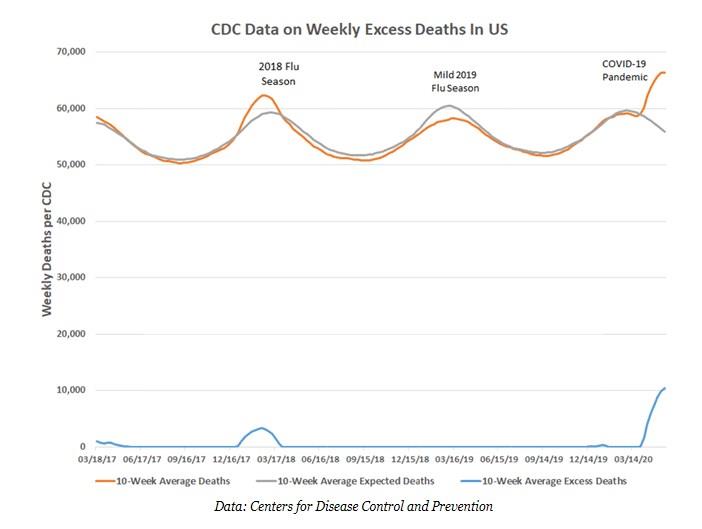

Contrast that with New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey where deaths as a percent of population were much higher. Medical facilities were stretched to their limits and had to reuse protective equipment. New York City had 24,000 “excess deaths” from March 11 to May 2, of which only 14,000 were confirmed COVID-19 cases.

New York City, with 2.5% of the US population, had 29.2% of the country’s excess deaths. If you exclude New Jersey and New York state, US excess deaths were only about 10% more than normal—compared with 5% for Germany, 25% for France, and 40% for Italy. There is a lot of speculation about why, but no definitive data.

And it is not simply population density. Hong Kong is far more dense and has a fraction of the deaths as New York. We don’t know why regional and state statistics vary so widely. Again, lots of speculation.

Think COVID-19 is just another flu? The CDC data say otherwise. Excess deaths are a very real thing. (H/T Rob Arnott)

The good news? If you are not in New York, New Jersey, or Connecticut, and are under 50 and healthy, your odds of dying from COVID-19 are low, in the range of a car accident. But that doesn’t mean you can ignore the risk, because you are around people who don’t have your luck. Any of us could be asymptomatic carriers. Plus, we are seeing longer-term side effects from the virus. Even if you survive, you don’t want to risk getting it (see below).

A second thing we do not understand about this virus is whether it generates enough of an immune response to prevent reinfection and how long that immune protection lasts. For that reason, even sophisticated antibody testing will not be very beneficial until we know more.

This also means vaccine development will require larger and longer tests that show decreased infections in the randomized group that receives an active vaccine as compared to the placebo group. That will take longer. Ugh. We all want faster but… we have to be safe and sure.

For the record, we are both firm believers that, with 100+ “shots on goal” happening from various groups around the globe, we will have a vaccine. It is too soon to know how many of these efforts will succeed but we think at least one will.

Moving on to what we do understand…

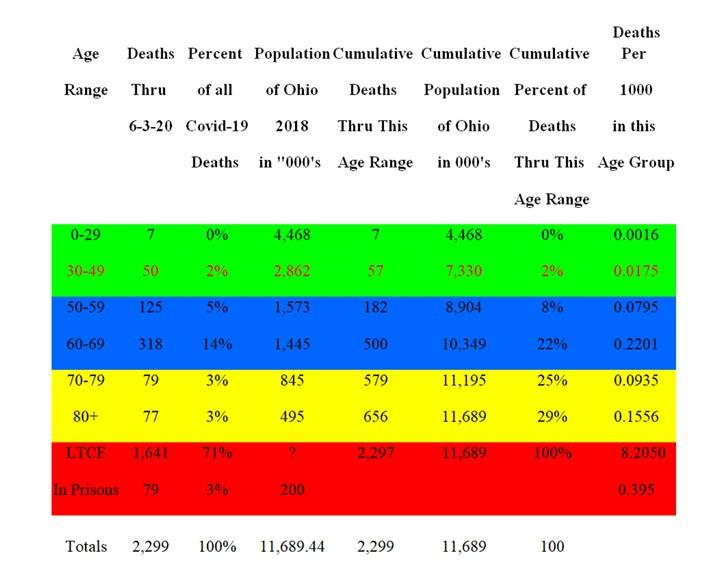

We are learning some of the factors influencing death from SARS-CoV-2: More than 70% of Ohio deaths have been residents in long-term care facilities. It is not uncommon if you are in an LTC facility to have one or more comorbidities and/or a compromised immune system. Because of residents’ close proximity, these places are like petri dishes for the virus. And not just here: over half of Sweden’s deaths have been in care facilities.

Ohio and a few other states track where the hospital patients came from, which many states (like New York) do not. Ohio data is thus more reliable in terms of determining which portions of the population are at risk. The data below (through Thursday) shows deaths by age, then separately those of all ages who died in LTC facilities and prisons.

(Notes: Estimates of proportion of 70–79 & 80+ deaths “in” and “not in” LTC facilities based on extrapolation of data from 4/29 to 5/06, and actual deaths in LTCFs. (There may be small statistical variances. We don’t know the ages of the people who died in prisons, but presume they are largely under age 70.)

We assume the higher mortality rate for 60–69 is because they have not yet gone to LTCFs and that the seemingly lower rate of older groups is because their age cohorts are disproportionally found in the LTCF death data. Mortality risk does indeed increase with age.

So outside of those in confined spaces, the risk of dying from COVID-19 for the rest of the Ohio population was approximately 51 deaths per million people. But like the seasonal flu, SARS-CoV-2 deaths are much higher in those over age 70, especially with uncontrolled high blood pressure or severe obesity, even if not in a long-term care facility.

Clearly, the older you are the more at risk you are. While we all technically knew that, the data here is from a large database and is pretty incontrovertible. In the future, we all know we must do better at LTC facilities. We also know that is easier said than done.

We also know how “you can protect you” if you are at risk, and what you need do to protect others:

How You Can Protect You:

-Physical distancing as much as reasonably possible and isolation for high-risk populations

-Washing your hands especially before touching face and eating

-Heat or re-heat food to 140 for 15 min.

-PPE: hats, N95 masks, and even gloves for high-risk populations

How You Can Protect Others:

-Physical distancing: 6+ feet

-Cloth or N95 masks, plus special gear for certain occupations

-Seek testing and quarantine yourself with symptoms like cough, fever, diarrhea, etc.

With over 100,000 deaths and rising, we need to do much better planning for a recurrence that is likely in the fall/winter or, if we avoid that, for the next new virus. This is especially so for hospital and ICU facilities, and understanding that the risk is mainly in the elderly, those with immune dysfunction, and those in LTCFs.

We can’t stress this enough: If you are in a high-risk population (age, high blood pressure, obesity, compromised immune system, etc.) you need to take precautions not only to protect yourself from getting sick—if you work or live around those at risk, you need to take precautions to protect them, too.

Secondary Consequences

The economic consequences are really secondary effects of the lockdown. You know them: 40 million unemployed, an enormous GDP drop, a huge government reaction, with the Fed doing everything it can, and Congress adding trillions in deficit spending.

The secondary medical effects are due to the response to economic effects and to fear: We do not have solid enough data on the deaths of despair to see if they outweigh COVID-19 deaths. But anecdotally, we are seeing an increase in suicides, opioid use, an increase in alcohol-related deaths (alcohol tax revenue has increased over 25% in places, and cigarette tax revenue up over 10%). Methamphetamine use has jumped as well.

In addition, many cancer patients are avoiding diagnostic testing and even chemotherapy visits. Dr. Scott Atlas, a physician and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, and his team have combed through public health records and actuarial tables to put a number on the devastating non-economic consequences of the virus lockdowns. They believe “they will be far beyond what the virus itself has caused.” Their report makes sober reading:

“Lives also are lost due to delayed or foregone health care imposed by the shutdown and the fear it creates among patients. …Emergency stroke evaluations are down 40 percent. Of the 650,000 cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in the United States, an estimated half are missing their treatments. Of the 150,000 new cancer cases typically discovered each month in the US, most—as elsewhere in the world—are not being diagnosed, and two-thirds to three-fourths of routine cancer screenings are not happening because of shutdown policies and fear among the population. Nearly 85 percent fewer living-donor transplants are occurring now, compared to the same period last year. In addition, more than half of childhood vaccinations are not being performed, setting up the potential of a massive future health disaster.”

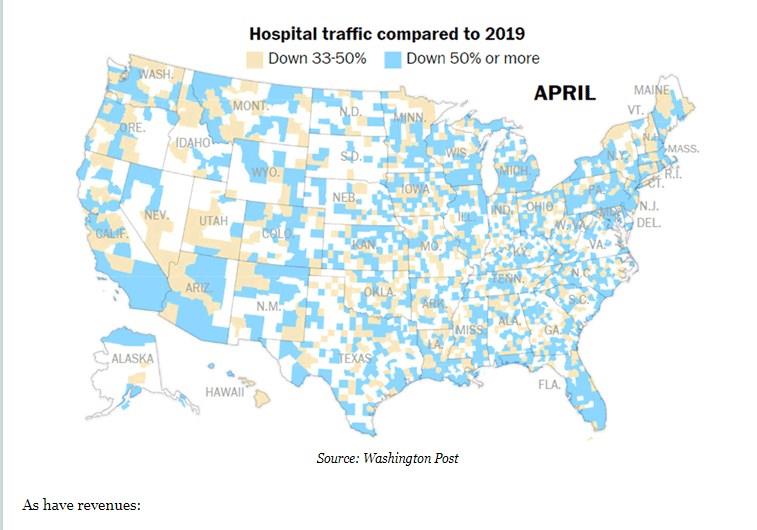

This is echoed graphically in a Washington Post article.

By mid-May, almost 94 million adults had delayed medical care because of the coronavirus pandemic, the Census Bureau reported in its Household Pulse Survey. Some 66 million of those needed but didn’t get medical care unrelated to the virus.

The Post’s data shows hospital traffic has collapsed:

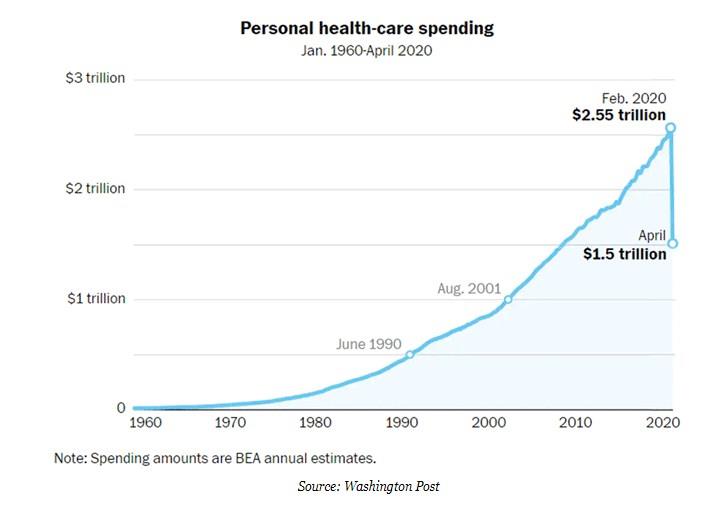

One result of this financial stress: 1.4 million healthcare jobs disappeared in April, according to the latest monthly government jobs report. Those included nearly 135,000 jobs lost at hospitals, more than 243,000 at physician offices and more than 503,000 at dental offices.

The Cleveland Clinic received $199 million from the federal government for its shutdown of normal care, but still lost $230 million in April—it would have been $429 million without that aid—and lost another $120 million in the first half of May. Still, even with government help, revenues in just a short period for all hospitals are down more than $1 trillion on an annualized basis. That has to come from somewhere, either cuts or increased costs or…?

The good news is that elective surgery at the Cleveland Clinic is back to 85+% of its pre-shutdown level. Note: “Elective” surgery is still necessary. It generally includes surgeries that are not needed immediately, but otherwise very important, like knee or hip replacements, or cataract removal.

Decreased access to medical care could occur as workers lose employer-sponsored health coverage due to layoffs (nearly 27 million according to one study) and by rural hospitals going out of business. On the positive side, telemedicine has been pulled forward, and will increase access for many. At the Cleveland Clinic, telemedicine visits went from 3,000 in February to over 200,000 in April—while much is being done to encourage that to continue, more patients are also choosing personal visits now.

Finally, some unexpected but possibly good news.

Contrary to common belief, the sun’s UV rays do not necessarily kill bacteria and viruses. UVA and UVB—what the sun provides—are very weak killers of bacteria and viruses. UVC, also provided by the sun but filtered out almost totally by the ozone layer, is what kills viruses and bacteria.

UVC at certain wavelengths is dangerous to humans but is sometimes used in sanitizing equipment like New York City subway cars (at night in the MTA barns). However, certain types of UVC light will kill bad invaders without damage to people.

Work on devices to do this was already underway before COVID-19. Could such lights make all of us safer? I (Mike) am asking a company that makes them to study whether dining and medical exam rooms could be made safer with these lights. Not to mention public sports venues. Both of these would be enormous game-changers and could happen pre-vaccine.

Even if We Get a Vaccine…

The most discouraging statistic for preventing the virus from killing Americans came from a new AP-NORC poll that found only about half of Americans say they would get a COVID-19 vaccine if one is developed. That’s surprisingly low considering the global effort going into a vaccine. African Americans and Hispanics are even less willing, even though the virus is proving more dangerous to those groups. Clearly people will need convincing to roll up their sleeves.

The virus should be convincing enough. Yes, while most people who get COVID-19 have mild cases and recover, doctors are discovering the coronavirus attacks in far sneakier ways than pneumonia—from blood clots to heart and kidney damage to a life-threatening inflammatory reaction in children. Whatever the final statistics show, health specialists agree the new coronavirus appears deadlier than the typical flu. Yet the survey suggests a vaccine would be no more popular than the yearly flu shot.

The pandemic is also causing global issues. The director of the World Food Program says the number of people facing hunger has doubled to 265 million because of COVID-19. But not all is dire overseas. In spite of our frustration with China, they managed to test 10 million people in one week in Wuhan this last week—1.4 million a day.

So, to go back to our opening question, we conclude there is a mask paradox:

Wearing a mask in confined spaces in public venues and enclosed spaces, while not perfect, will help protect you and those around you. But it will also help in other ways.

We have to get the economy moving again, which means people have to participate by leaving home to visit stores, restaurants, etc. They have to feel safe doing so. Wearing a mask, while admittedly annoying and uncomfortable, gives others confidence, especially older people. And typically, they have more disposable income, and we all need them to be confident and participate in the economy.

Said another way: Seeing crowds of unmasked people is frightening to a large part of the population. It encourages them to stay home and cut spending. This further delays economic recovery. We will get back to normal much faster if we all cooperate and help the vulnerable people return to society without undue fear.

Finally, remember: Your immune system is a highly organized and responsive unit. It is designed to protect you. So help it: Get your flu shot as soon as it is offered this year. No matter how great the Cleveland Clinic is as a health mecca, not to mention the other great healthcare facilities nationwide, they do not have enough capacity to handle a major flu epidemic and a recurrent COVID-19 outbreak at the same time.

Bottom Line

We have to open up the country, from both a medical and economic perspective. Continuing lockdowns may cause more deaths for other reasons. The economic pain is real and obvious.

But we have to open up smartly. We have to realize who is at risk and take care of them responsibly. We need to be more aware of our neighbors and their needs, doing what we can to help. We have to create a sense of security for everyone, even if that means minor personal annoyances that we might think unjustified.

Without everyone participating, the economy and public health are at risk. We had serious problems with healthcare access before this virus. It is going to get worse if we don’t work together.

Things will get better. There will be a vaccine. But we have to buy the time to get to that point and that means we all need to do our part.

*first published in: www.mauldineconomics.com

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer