by Greta Keenan*

-Edward Jenner developed the first vaccination to prevent smallpox.

-Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, aims to lower vaccine prices for the poorest countries.

-The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation (CEPI) works to accelerate the development of vaccines against emerging diseases.

It is no secret that vaccinations have revolutionized global health. Arguably the single most life-saving innovation in the history of medicine, vaccines have eradicated smallpox, slashed child mortality rates, and prevented lifelong disabilities.

Possibly lesser known, however, are the historic events and pioneers we can today thank for not only saving millions of lives each year, but for laying the foundations of future vaccine development – something that is front-of-mind as the world rushes to make a viable coronavirus vaccine.

Early attempts to inoculate people against smallpox – one of history’s most feared illnesses, with a death rate of 30% – were reported in China as early as the 16th Century. Smallpox scabs could be ground up and blown into the recipient’s nostrils or scratched into their skin.

The practice, known as “variolation”, came into fashion in Europe in 1721, with the endorsement of English aristocrat Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, but was later met with public outcry after it transpired 2-3% of people died after inoculation, and further outbreaks were triggered.

The next iteration of inoculation, which turned out to be much safer than variolation, originated from the observation that dairy farmers did not catch smallpox. The 18th Century English physician, Edward Jenner, hypothesised that prior infection with cowpox – a mild illness spread from cattle – might be responsible for the suspected protection against smallpox. And so, he set to work on a series of experiments, now considered the birth of immunology, vaccine therapy, and preventive health.

In 1796, Jenner inoculated an eight-year-old boy by taking pus from the cowpox lesions on a milkmaid’s hands and introducing the fluid into a cut he made in the boy’s arm. Six weeks later, Jenner exposed the boy to smallpox, but he did not develop the infection then, or on 20 subsequent exposures.

In the years that followed, Jenner collected evidence from a further 23 patients infected or inoculated with the cowpox virus, to support his theory that immunity to cowpox did indeed provide protection against smallpox.

The earliest vaccination – the origin of the term coming from the Latin for cow (“vacca”) – was born. Jenner’s vaccination quickly became the major means of preventing smallpox around the world, even becoming mandatory in some countries.

Almost a century after Jenner developed his technique, in 1885, the French biologist, Louis Pasteur, saved a nine-year-old boy’s life after he was bitten by a rabid dog, by injecting him with a weakened form of the rabies virus each day for 13 days. The boy never developed rabies and the treatment was heralded a success. Pasteur coined his therapy a “rabies vaccine”, expanding the meaning of vaccine beyond its origin.

The global influence of Louis Pasteur led to the expansion of the term vaccine to include a long list of treatments containing live, weakened or killed viruses, typically given in the form of an injection, to produce immunity against an infectious disease.

Scientific advances in the first half of the 20th Century led to an explosion of vaccines that protected against whooping cough (1914), diphtheria (1926), tetanus (1938), influenza (1945) and mumps (1948). Thanks to new manufacturing techniques, vaccine production could be scaled up by the late 1940s, setting global vaccination and disease eradication efforts in motion.

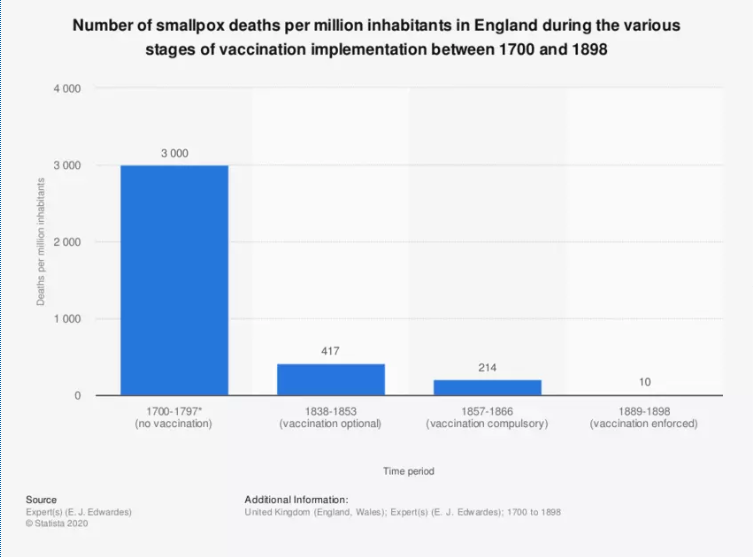

Vaccines against polio (1955), measles (1963), rubella (1969) and other viruses were added to the list over the decades that followed, and worldwide vaccination rates shot up dramatically thanks to successful global health campaigns. The world was announced smallpox-free in 1980, the first of many big vaccine success stories, but there was still a long way to go with other infectious diseases.

By the late 1990s, the progress of international immunization programmes was stalling. Nearly 30 million children in developing countries were not fully immunized against deadly diseases, and many others weren’t immunized at all. The problem was that new vaccines were becoming available but developing countries simply could not afford them.

In response, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and partners came together in 2000 to set up the Global Alliance for Vaccines and immunization, now called Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. The aim was to encourage manufacturers to lower vaccine prices for the poorest countries in return for long-term, high-volume and predictable demand from those countries. Since its launch, child deaths have halved, and 13 million deaths have been prevented.

Protecting against long-standing illnesses will continue to be important in the decades and centuries ahead, but the work is not complete. In order to protect the world against infectious diseases, we need a mechanism to monitor new viruses, and rapidly develop vaccines against the most dangerous emerging infections. The devastating 2014/2015 Ebola virus was a wake up call for how ill-prepared the world was to handle such an epidemic. A vaccine was eventually approved but came too late for the thousands of people who lost their lives.

In response, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation (CEPI) was launched at Davos in 2017, a global partnership between public, private, philanthropic, and civil society organizations working to accelerate the development of vaccines against emerging infectious diseases and enable equitable access to these vaccines for affected populations during outbreaks.

We’ve come a long way since the risky and gruesome early inoculation efforts five centuries ago. Scientific innovation, widespread global health campaigns, and new public-private partnerships are literally lifesavers. Finding a vaccine to protect the world against the new coronavirus is an enormous challenge, but if there’s one thing we can learn from history, it’s that there is reason for hope.

*Programme Specialist, Science and Society, World Economic Forum

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer