by Elke Van Hoof*

-With some 2.6 billion people around the world in some kind of lockdown, we are conducting arguably the largest psychological experiment ever;

-This will result in a secondary epidemic of burnouts and stress-related absenteeism in the latter half of 2020;

-Taking action now can mitigate the toxic effects of COVID-19 lockdowns.

In the mid-1990s, France was one of the first countries in the world to adopt a revolutionary approach for the aftermath of terrorist attacks and disasters. In addition to a medical field hospital or triage post, the French crisis response includes setting up a psychological field unit, a Cellule d’Urgence Medico-Psychologique or CUMPS.

In that second triage post, victims and witnesses who were not physically harmed receive psychological help and are checked for signs of needing further post-traumatic treatment. In those situations, the World Health Organization recommends protocols like R-TEP (Recent Traumatic Episode Protocol) and G-TEP (Group Traumatic Episode Protocol).

Since France led the way more than 20 years ago, international playbooks for disaster response increasingly call for this two-tent approach: one for the wounded and one to treat the invisible, psychological wounds of trauma.

In treating the COVID-19 pandemic, the world is scrambling to build enough tents to treat those infected with a deadly, highly contagious virus. In New York, we see literal field hospitals in the middle of Central Park.

But we’re not setting up the second tent for psychological help and we will pay the price within three to six months after the end of this unprecedented lockdown, at a time when we will need all able bodies to help the world economy recover.

The mental toll of quarantine and lockdown

Currently, an estimated 2.6 billion people – one-third of the world’s population – is living under some kind of lockdown or quarantine. This is arguably the largest psychological experiment ever conducted.

Unfortunately, we already have a good idea of its results. In late February 2020, right before European countries mandated various forms of lockdowns, The Lancet published a review of 24 studies documenting the psychological impact of quarantine (the “restriction of movement of people who have potentially been exposed to a contagious disease”). The findings offer a glimpse of what is brewing in hundreds of millions of households around the world.

In short, and perhaps unsurprisingly, people who are quarantined are very likely to develop a wide range of symptoms of psychological stress and disorder, including low mood, insomnia, stress, anxiety, anger, irritability, emotional exhaustion, depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Low mood and irritability specifically stand out as being very common, the study notes.

In China, these expected mental health effects are already being reported in the first research papers about the lockdown.

In cases where parents were quarantined with children, the mental health toll became even steeper. In one study, no less than 28% of quarantined parents warranted a diagnosis of “trauma-related mental health disorder”.

Among quarantined hospital staff, almost 10% reported “high depressive symptoms” up to three years after being quarantined. Another study reporting on the long-term effects of SARS quarantine among healthcare workers found a long-term risk for alcohol abuse, self-medication and long-lasting “avoidance” behaviour. This means that years after being quarantined, some hospital workers still avoid being in close contact with patients by simply not showing up for work.

Reasons for stress abound in lockdown: there is risk of infection, fear of becoming sick or of losing loved ones, as well as the prospect of financial hardship. All these, and many more, are present in this current pandemic.

The second epidemic and setting up the second tent online

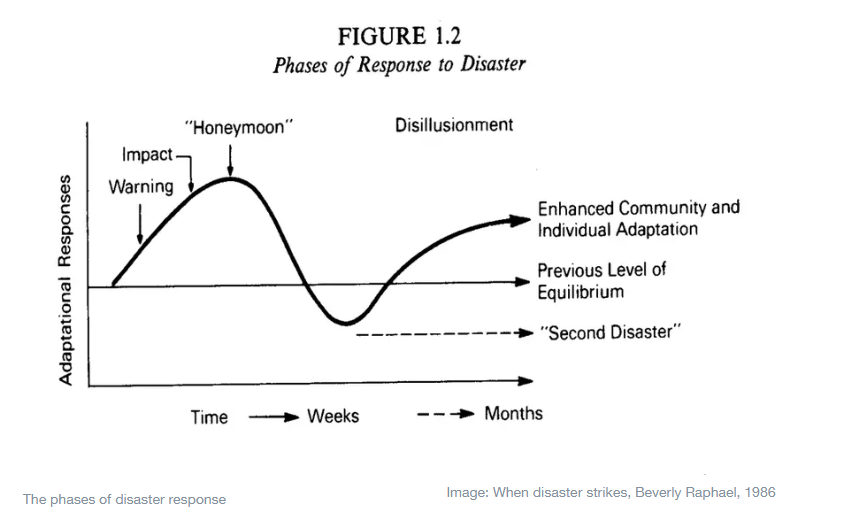

We can already see a sharp increase in absenteeism in countries in lockdown. People are afraid to catch COVID-19 on the work floor and avoid work. We will see a second wave of this in three to six months. Just when we need all able bodies to repair the economy, we can expect a sharp spike in absenteeism and burnout.

We know this from many examples, ranging from absenteeism in military units after deployment in risk areas, companies that were close to Ground Zero in 9/11 and medical professionals in regions with outbreaks of Ebola, SARS and MERS.

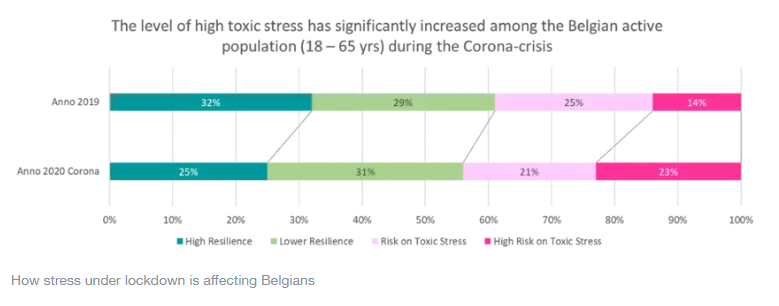

Right before the lockdown, we conducted a benchmark survey among a representative sample of the Belgian population. In that survey, we saw that 32% of the population could be classified as highly resilient (“green”). Only 15% of the population indicated toxic levels of stress (“red”).

In our most recent survey after two weeks of lockdown, the green portion has shrunk to 25% of the population. The “red” part of the population has increased by 10 percentage points to fully 25% of the population.

These are the people at high risk for long-term absenteeism from work due to illness and burnout. Even if they stay at work, research from Eurofound reports a loss of productivity of 35% for these workers.

In general, we know at-risk groups for long-term mental health issues will be the healthcare workers who are on the frontline, young people under 30 and children, the elderly and those in precarious situations, for example, owing to mental illness, disability and poverty.

All this should surprise no one; insights on the long-term damage of disasters have been accepted in the field of trauma psychology for decades.

But while the insights are not new, the sheer scale of these lockdowns is. This time, ground zero is not a quarantined village or town or region; a third of the global population is dealing with these intense stressors. We need to act now to mitigate the toxic effects of this lockdown.

What governments and NGOs can and should do today

There is broad consensus among academics about the psychological care following disasters and major incidents. Here are a few rules of thumb:

-Make sure self-help interventions are in place that can address the needs of large affected populations;

-Educate people about the expected psychological impact and reactions to trauma if they are interested in receiving it. Make sure people understand that a psychological reaction is normal;

-Launch a specific website to address psychosocial issues;

-Make sure that people with acute issues can find the help that they need

In Belgium, we recently launched Everyone OK, an online tool that tries to offer help to the affected population. Using existing protocols and interventions, we launched our digital self-help tool in as little as two weeks.

When it comes to offering psychological support to their populations, most countries are late to react, as they were to the novel coronavirus. Better late than never.

*Professor, health psychology and primary care psychology, Vrije Universiteit Brussel

**first published in: www.weforum.org

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer