Last year, the world economic activity continued to expand rapidly, driven by growth in the USA and China.

In 2005, and especially within the first half of the year, world economic activity continued to expand rapidly, driven by growth in the United States (independently of the hurricanes that devastated the Gulf of Mexico in September) and China. The protraction of favorable financial conditions, reflecting positively on the value of capital assets, buoyed investment and consumer demand. In the main industrial countries, economic activity was only marginally affected by the further large and unexpected rise in energy prices, thanks in part to the declining energy-intensiveness of production. In the US, the highly expansionary impetus of economic policy since 2001 waned. Trade in goods among the main industrial countries again expanded strongly (up 4.9% on an annual basis in the first half of 2005 from the previous period) albeit at a slower pace than in the second half of 2004 (7.4%).

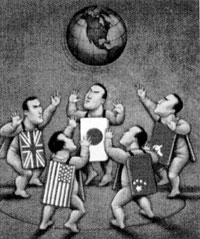

The growth gaps between the main industrial regions of the world remained large: in contrast with the strong expansion in the US, economic activity was slack in the euro area and decelerated brusquely in the United Kingdom. Only in Japan was economic recovery faster than expected. The global payments imbalances sharpened: persistent disparities in demand trends were compounded by the rise in oil prices. This led to a massive transfer of resources from consumer to producer countries, which used only a portion to expand imports: the IMF estimates that the growth in oil-producing countries` imports by value accelerated from 22% in 2004, to 24% last year. The deficit in the US balance of payments on current account exceeded 6% of GDP, amounting in the first six months to nearly $800 billion on an annual basis. At the end of 2004, the US net foreign debtor position was 22% of GDP. Nonetheless, the dollar began to strengthen at the beginning of 2005, buoyed by large inflows of private capital as current and expected short-term interest rate differentials widened in its favour.

In the US, private consumption remained the main driver to output, which grew by 3.6% in the first three quarters compared with the year-earlier period. The effect of the rise in oil prices on households` disposable income was offset by the rise in unemployment. Thanks to conditions on the mortgage loan market, the further gains in property prices enabled households to increase both their debt and their liquid assets. Their propensity to save continued to decline, turning slightly negative in the summer: it has fallen by 5 percentage points since the mid-1990s. In the first half of 2005, total private sector saving diminished from 4.7% to 3.9% of GDP. The national saving rate, reflecting the improvement in the public finances, rose from 1.2% to 1.6% of GDP. The rise in energy costs pushed consumer prices up significantly, but did not affect core inflation or expectations, which remained moderate. The Federal Reserve proceeded with the gradual attenuation of expansive monetary conditions begun in the middle of 2004, raising the target rate on federal funds to 4%.

In the euro area, economic activity remained sluggish in the first half of 2005 as well. The expected upswing in capital spending did not materialize and investment stagnated. Exports continued to rise at a slower pace than world trade. Only public and private consumptions sustained growth. Early official estimates indicate acceleration in economic activity in the first quarter of this year.

Japan overcame the weakness that had characterized much of 2004: output resumed rapid growth under the stimulus of private demand, rising in the first half of the year at an annualized rate of 4%; in the third quarter it slowed to 1.7%. The increase in employment and waged boosted household consumption; the improvement in firms` profitability and balance sheet situation, together with the progress made in restructuring the banking sector, set investment in motion again.

In the United Kingdom, output growth slowed to 1.5% on an annual basis in the first half of 2005. There was a further, larger-than-expected deceleration in consumption growth to 1.3%, from 2.9% in the second half of 2004. The lagged effects of the monetary tightening by the Bank of England between November 2003 and August 2004 were compounded by the slowdown in house prices beginning in the summer of 2004. In August this year, the central bank reduced the reference rate by 0.25 basis points to 4.5%.

In the United States, notwithstanding the repeated raising of official rates, yields on long-term government bonds did not vary significantly. Firms` profitability kept the risk premiums on corporate bonds low; share prices held steady at the levels of end-2004; their variability was limited. In the emerging economies the yield differentials between dollar-denominated government securities and the corresponding US Treasury securities remained narrow. They benefited not only from the strengthening of the respective underlying economic variables, but also from a greater propensity to invest in more risky instruments.

In the majority of countries, nominal and real long-term interest rates remained low. This was generally believed to be due in part to a reduction in risk premiums owing to the lower observed and expected variability of economic growth and inflation. A largely unexpected structural rise in the demand for long-term securities was probably caused in the first place by an increase in liquidity and savings in some emerging areas –particularly in Asia and more recently in the oil-exporting countries– in conjunction with slower investment growth; various amendments to the regulations governing institutional investors in the industrial countries aimed at bringing the duration of assets into line with that of liabilities also contributed by causing a permanent increase in the volume of ten-year bonds in the portfolios of pension funds and insurance companies. Since neither of these factors is likely to change, at least in the short run, they will continue to curb the rise in long-term yields. However, the low levels of real long-term interest rates contrast with the sharp acceleration in productivity over the last decade, particularly in the US.

In September 2005, the Financial Stability Forum pointed to several phenomena whose persistence could cause tensions on the market. They include the exceptionally low levels of spreads and long-term interest rates, the popularity of increasingly complex financial instruments, household debt and growing external account imbalances and budget deficits. Operators, regulators and economic policy-makers were called upon to tighten market regulations and credit rating procedures, to raise operational standards and to increase allocations to risk provisions.

In July 2005, the Chinese monetary authorities enacted a reform of the exchange rate system to increase flexibility and facilitate domestic liquidity control. The reorganization of the banking sector under way for the last two years, the increase in recourse to market instruments for monetary policy management and the changes to the exchange rate system are part of a policy of gradually liberalizing the financial system. Among other benefits, this would make for a more efficient allocation of national savings, which amount to 49% of GDP.

The strains in the oil market have worsened in recent months, partly owing to natural disasters. The average price of the three main grades rose from $40 a barrel at the end of 2004, to over $58 in October 2005. During the year, while world energy-demand increased significantly, short-term supply became progressively more rigid, amplifying price reactions. Future prices on WTI grade contracts (on NYMEX on 11 November) indicate that in March 2006 the price of oil will top $59 a barrel, slightly more than spot prices, and remain virtually unchanged for the rest of the year.

Under these circumstances, we can forecast that the year 2006 will be a positive one, especially for the emerging economies.

By: N. Peter Kramer

By: N. Peter Kramer